The Guernsey Literary Festival isn’t the most likely place you’d expect to find John Cooper Clarke. As a punk poet who rose to fame touring with the likes of Joy Division, the Sex Pistols and The Fall, his explosive (and expletive-littered) poetry rails against the mundane and the comfortable. Quite a contrast, then, to the rest of the festival’s line-up, which features cosy readings of The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie and family-friendly workshops.

Having performed alongside legendary acts on the 1970s Manchester club scene and released six acclaimed albums, the Bard of Salford has become an iconic figure in cultural memory as well as punk literature. His best-loved poetry has become a byword for urban discontent and youthful revolt. However, that his work now features on the GCSE syllabus suggests an over-simplification of what he’s trying to say: while his work should be taught in schools, the addition of ‘Twat’ to exam papers has arguably placed Cooper Clarke in the region of ‘novelty’ rather than ‘seminal’.

Perhaps because his reputation precedes him, it’s difficult to separate the man from his work. We have a received idea of what he’s supposed to stand for and pigeonhole his genius along with his contemporaries, rather than viewing him as a working artist with an individual voice. For all we’ve heard of John Cooper Clarke, we’ve not really been listening to him.

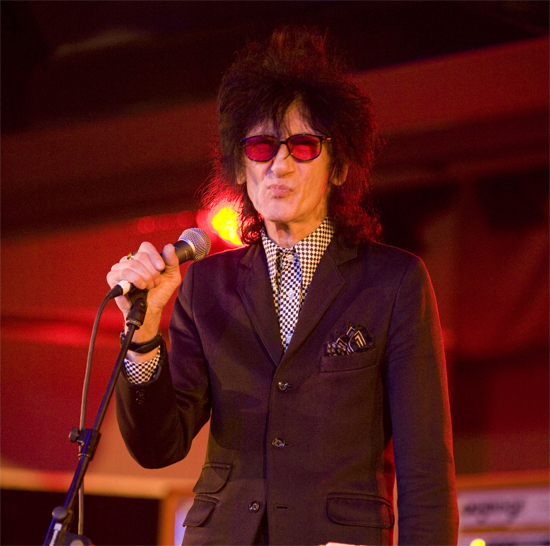

After a long stint away from the stage and its accompanying hype, Cooper Clarke has only returned to the performance poetry circuit relatively recently. And while gig-goers flock to see him with the hope of witnessing a piece of cultural, cuss-filled history – counting myself among them – he’s not the anachronistic curiosity that I had expected. Pin-thin and sharp-tongued, Cooper Clarke shambles on stage with his trademark coiffure and dark glasses. His eyesight may be going and you may well question whether the hair’s all his, but Cooper Clarke’s poetry hasn’t aged with him. Often offensive, always charming, he clearly relishes having an audience and quickly builds up a rapport.

Cooper Clarke’s patter is as outrageously funny as his poetry. His swaggering stage persona belies a viciously articulate and self-aware artist, with a pathological gift for observation and the sly delivery of a stand-up. From smutty limericks about STDs to bleak asides about homeless people and pension funds, there’s no topic that this poet won’t leave with its dignity intact. He reshapes the mundane into the shocking and the shocking into something far worse, and you’ll be beaten into laughing whether you like it or not. Four-letter-filled favourites such as ‘Burnley’ and ‘Hire Care’ elicit shrieks of delight from the audience.

His manipulation of language is inventive and surprising, twisting our pre-conceived image of him from one joke to the next. He even mocks his own aggressiveness and bad taste, pronouncing himself harmless with the quick quip, ‘I don’t give a fuck really, and I don’t think wars were ever started by anyone who didn’t give a fuck.’

It’s not all angry, either. Cooper Clarke’s best-known verses glimpse into the despair and absurd monotony of urban living, as famously laid bare in ‘Evidently Chickentown’, which rages against life in a dead-end English town. However, there’s an unanticipated range within his work too. This is exemplified by his insight into the institution of marriage, ‘I’ve Fallen in Love with My Wife’. It’s almost sweet – sweetly sardonic – and just goes to show that our expectations of what poetry Cooper Clarke is capable of composing are hugely limited.

His newer work reveals poignancy beneath its irreverence. Age is a prominent theme and, being the unabashed and outspoken artist that he is, his words needle at society’s unspoken fears and taboos. ‘I don’t want to live in a bungalow that smells of piss and biscuits,’ is as much a heartfelt plea from a 62-year-old rocker as it is a send-up of dreary stereotypes. Vince, the ‘ageing savage’ who reeks of cabbage and gloom in his earlier poem ‘Beasley Street’, is precisely the image of old age that Cooper Clarke despises and actively defies. Laughing at mortality doesn’t make it seem so scary; the fatalism of ‘Things Are Only Going to Get Worse’ isn’t lessened by the humour, rather the humour unifies the audience in facing it. This is not an artist writing new work from within a vacuum, simply unearthing 1970s relics or removing himself from current context: his work remains subversive but its focus is shifting with his experience.

This gives his work a real relevance. He’s recently written a companion piece for ‘Beasley Street’, which is sneeringly titled ‘Beasley Boulevard’. While the former poem grimaced at the insignificance of existence in a suburban dump, its latest reincarnation jibes at pretentiousness and consumerism with such scornful remarks as, ‘Never been on TV, you say, how very avant-garde.’ It’s still the same street, he implies, the same routine misery: just with a celebrity makeover.

Punk subculture has of course influenced his poetry and his stylized delivery but what he’s got to say goes beyond specific genres. You don’t have to view his work from a retrospective standpoint – or even be a fan of punk literature – to grasp what he’s got to say and the urgency with which he’s saying it. He’s not repeating old work for the sake of it but is presenting us with a very relevant and responsive commentary on what he sees as happening now. Apparently Cooper Clarke has declined interview requests for years on the basis of having no new work, so that he’s now back in the public eye reaffirms this idea that he’s crafted something new to say that requires us to listen, rather than pre-empt his words and values. As the Guernsey Literary Festival has endeavoured to include him in their programme at all, this hopefully suggests that his life’s work – both old and new – is beginning to receive the wider audience it deserves. Disaffection and disappointment are everywhere in our society at the moment, and John Cooper Clarke’s wry and sometimes surreal take on the human condition may be the antidote.