For the last few years, most of the music industry – in all its forms, from record labels to artist managers, from music publishers to concert promoters – has been railing against illegal downloading, arguing that such activity is bringing the business to its knees, and pursuing those engaged in it, whether websites like The Pirate Bay or individuals, for every penny they believe they are owed. In March this year, for instance, the RIAA – the Recording Industry Association of America – and a group of thirteen record labels went to court in New York in pursuit of a case filed against Limewire in 2006 for copyright infringement. The money owed to them – the labels involved included Sony, Warner Brothers and BMG Music – could be, they argued, as much as $75 trillion. With the world’s GDP in 2011 expected to be around $65 trillion – $10 trillion less – this absurd figure was, quite rightly, laughed out of court by the judge. The RIAA finally announced in mid May that an out of court settlement for the considerably lower sum of $105 million had been agreed with Limewire’s founder.

But while fans have been warned that without traditional income streams investment in new acts will be harder, musicians have at the same time been told by the wider industry that there are still plenty of opportunities for them to make a living if they reverse long held principles: touring is now where the money is and records, cheap or even free, should be used to promote live performance. In addition, licensing music to TV, film and advertising, the prevailing opinions insist, is no longer a dirty business and can provide significant opportunities to claw back income while social networking allows direct to fan marketing that cuts out the middle men who previously took their cut.

All the time the industry talks of money: money it’s lost, money it’s owed. It rarely talks about the effects upon artists, and even less about how music itself might suffer. But no one cares about the suits and their bank accounts except shareholders and bankers. People care about their own money, and the industry not only wanted too much of it but also failed to take care of those who had earned it for them: the musicians. And it’s the latter that people care about. Because People Still Want Good Music.

It’s ‘Good Music’ that is now at stake, however. The effects upon musicians of the downturn in income are far more complex than that they simply won’t be able to, as Lily Allen put it, “go on”, and to blame filesharers exclusively is short-sighted. Things have now gone beyond that. Industry inertia, caused by a refusal to recognise a change in how people consume music – arguably provoked by greed on an even bigger scale than that exhibited by those who want their music for free – is causing substantial damage to the artistic process and may create a situation where only those with existing wealth can pursue the craft. It’s also perhaps not too much to argue that a further result will be the silencing of voices that are vital to democratic society.

But if the industry wants to talk money, let’s talk money, albeit the ways that developing musicians are encouraged to make up the loss of sales income in order to ply their trade. Someone’s got to bring this up, because it’s not a pretty picture. Consider, first, direct-to-fan marketing and social networking, said to involve fans so that they’re more inclined to attend shows, invest in ‘product’, and help market it. In practise this is a time-consuming affair that reaps rewards for only the few. Even the simple act of posting updates on Facebook, tweeting and whatever else is hip this week requires time, effort and imagination, and while any sales margins subsequently provoked might initially seem higher, the ratio of exertion to remuneration remains low for most. It’s also an illusion that such sales cut out the middlemen, thereby increasing income, except at the very lowest rung of the ladder: the moment that sales start to pick up, middlemen start to encroach upon the artist’s territory, if in new disguises. People are needed to provide the structure through which such activities can function, and few will work for free – and nor should they – even though musicians are now expected to.

In addition, efficient websites need to be paid for and marketed, and the companies designed to provide exactly this service usually take their cut. Bandwidth also needs to be paid for if up- and downloading become significantly active, product needs to be manufactured and sent out on time, and that’s only after it’s been created, meaning music first needs to be recorded and merchandise designed. If new artists can’t find the readies for all this, then they need to find investors. So with music itself often available for free, the musician is reduced to little more than a merchandise broker. Records become just an advert and, consequently, either take longer to be written and recorded, or are otherwise made available without the attention and care that was once devoted to the process.

Still, if an act can find time to do these things, or has the necessary capital to allow others to take care of them on their behalf, then they can hit the road. Touring’s where the money is, the mantra goes, and that’s the best way to sell merchandise too. But this is a similarly hollow promise. For starters, the sheer volume of artists now touring has saturated the market. Ticket prices have gone through the roof for established acts, while those starting out are competing for shows, splitting audiences spoilt for choice, driving down fees paid by promoters nervous about attendance figures. There’s also a finite amount of money that can be spent by most music fans, so if they’re coughing up huge wads of cash for stadium acts then that’s less money available to spend on developing artists. And for every extra show that a reputable artist takes on in order to make up his losses, that’s one show less that a new name might have won.

Touring is also expensive. That’s why record labels offered new artists financial backing, albeit in the form of a glorified loan known as ‘tour support’. Transport needs to be paid for, as do fuel, accommodation, food, equipment, tour managers and sound engineers. These costs can mount up very fast, and if each night you’re being paid a small guarantee, or in fact only a cut of the door, then losses incurred can be vast, rarely compensated for by merchandising sales. Again, financial backing of some sort is vital, but these days labels are struggling to provide it. In the past, income from record sales could be offset against these debts, but with that increasingly impossible, new artists will soon find it very hard to tour. Everyone’s a loser, baby.

Furthermore, touring, especially in the early stages of a career, is exhausting. It might be fun, but as anyone who’s been on the road will admit, it can be a far from glamorous grind that leaves musicians drained, incapacitated and far from creative. It also seems off kilter that those gifted at writing and working in the studio should be sent out on the road rather than rewarded for just that, especially since records, in whatever format, are the ties that help bind fans to artists. There are also those for whom it’s not viable, or at the very least a challenge: those suffering from stage fright; those – mothers, for example – whose family situation requires them to remain at home; those skilled at writing songs but not so adept at performing them. (It’s notable that the likes of Jimmy Webb, who once made a comfortable living writing songs for others to perform, are now touring in a way that they never used to, largely out of financial necessity.)

Of course touring has always been a next to obligatory part of the job for most musicians. Some are even inspired by the experience, while many improve their craft by playing in front of audiences. But the daily rigmarole of playing the same songs over and over again can also render the process joyless for both musician and fan, and increased touring again means reduced time spent working on new material, conjuring up bewitching sounds, expressing the inarticulate speech of the heart. The romantic vision of the musician in their bus writing new songs is rose-tinted, to say the least. Most are simply too worn out from the tedium to do anything other than talk shit, watch films, listen to music and sleep. Insisting that artists earn their keep by performing the role of wandering minstrel keeps them from exercising the talent that brought them attention in the first place, rendering music valuable only when it’s performed live.

Still, there’s another well-publicised method of working around lost sales income. It’s called synchronisation, and that’s the licensing of music to TV, film and commercials. It was once a badge of honour to find one’s music selected for a soundtrack, but these days everyone’s at it so the benefits are fewer. It’s interesting to watch films like Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation or Nic Roeg’s Don’t Look Now from the early 1970s and compare their relative silence – interrupted effectively but only occasionally by bursts of music used to heighten tension or enhance a mood – with the extended music videos that pass for Hollywood movies nowadays. The same could be said for TV, where shows like Skins are so song-saturated that numerous websites exist listing each track included in an episode (though notably these are not listed in credits). Apart from anything else, so much music often dilutes the drama by distracting from it, but more importantly it makes it harder for an impressive song to stand out, especially a new one dwarfed by others more recognisable, while those that do rise above the noise are often forever associated with a particular scene, rendering their own emotional substance next to mute in comparison.

More worrying too is the manner in which old school values with regards to the licensing of music to advertising have been eroded. To be tainted by association with a product, to ‘sell out’ one’s art to benefit a corporation, was once seen as an evil undertaken only by the desperate, the immoral or – on the off chance that the brand was ethically sound – those fortunate enough to claim that they remained very selective. Yet in record company and music publishing meetings around the world there are now hip young things declaring that, instead of a single, they can’t hear a ‘synch’. Many have whole departments devoted to the placement of music wherever possible, and acts are expected to accept the offers. Often they’re in such a financial hole that they simply can’t say no. This has led not only to a complicit integration of music with product marketing, but also to lower and lower fees: agencies have realised that acts remain convinced that the exposure gained is in itself almost adequate compensation for the use of their music, and there’s always someone else willing to accept a lower payment if the first choice demands too much. But whatever the financial reward, the price paid is always the same: permanent association with a product. How tragic is it that the man behind ‘Anarchy In The UK’ will now be forever tied in the collective imagination with Country Life Butter, even though he used the cash to help fund the reformation of PiL? The argument that he has taken money from a corporation doesn’t wash: the situation should never have arisen.

And if that’s not compromise enough, what about the songs reduced to half minute edits, the songs that are used instrumentally, or the songs that are provided by soundalikes, thus debasing the art of those who first imagined the originals? What about the acts tailoring their music for use in these ways rather than focussing on their original intent, that of expressing something memorable? Is this good for our music? Is this how the magic should be rewarded?

It’s debatable, too, how easy it is to secure such breaks, given that everyone and their sister is now after their small slice of the action. The growth of music supervision as a profession has meant that many brands turn to those who represent established acts and, if they fail to secure their music, take recommendations from these same people about others they represent in order to save time. It’s an almost closed shop, and for a new act it’s next to impossible to get a foot in the door. Moreover, those who are successful, but for whom it’s their first public exposure, rarely make it beyond, tainted as they are by the connection. Simultaneously, the question arises once more as to whether acts should be devoting time to the pursuit of synchs at the expense of refining their craft, and whether they should only be receiving payment for the public use of their music as opposed to the private use.

It gets worse. The first people to give up will be those with the least money. This, some argue, will sort the wheat out from the chaff: serious musicians don’t give up that easily. But this is clearly nonsense. Serious musicians might not give up, and some may thrive – if the cliché is true – because they have suffered. But if they can’t afford to tour, record, build a website and pay those required to supervise their business, let alone pay their rent, then they won’t make music their priority and potential stars will be lost to us. Their guitars will gather dust, picked up to fill quiet time or, perhaps, to be strummed for friends in small bars. Maybe they’ll win fans, but most won’t be able to do anything with that fact. A developing act can’t tour anywhere unless it can afford to get there, and its products won’t be bought unless it can tour, because these days that’s one of the few ways to gain attention amidst the shrill shriek of marketing. The first hurdle any musician must now leap is financial: can they afford to pursue the dream?

The majority that succeed will be those well connected enough to receive funding, or those from financially comfortable backgrounds. This might explain the number of upper middle class artists that have made their mark recently, something which Quietus contributor Simon Price pointed to in an article for The Word in late 2010 about the ‘Toff Takeover’, where he highlighted the rise of artists like Eliza Dolittle, Florence Welch and Mumford & Sons who have all benefited from exclusive educations. Price suggested that those who ”didn’t go to a private school are no longer getting a fair shot at success”, and went on to state that, “it’s bad for pop. If music – along with sport, the traditional ‘escape route’ for the poor – is shut off, where is the next Johnny Rotten or Jarvis Cocker going to come from?”

It’s a point well made, if provoked a little by inverse snobbery, and there’s one further concern: those whose voices most need to be heard are often the ones least powerful, and musicians have frequently done far more than provide us with music. They’ve articulated thoughts that need to be heard. They’ve drawn our attention to injustices in the world just as they’ve highlighted the beauty of life. They have helped bring together communities and given them a common voice. They have spoken out and stood up for their principles, demanded change and sometimes achieved it. Our failure to find a satisfactory method in which their privileged situation – as commentators – can be protected could be very damaging. Though it inevitably sounds like a conspiracy theory, it may be more than coincidence that governments have taken so long to address the problems that the music business is facing. Music has provided a voice of dissent, and governments don’t like that. By failing to ensure that musicians have the same right to be paid for their work as anyone else, they’re helping to ensure that only the least controversial acts survive: those of independent wealth, often tied to the establishment; the ones that are happy to prop up the capitalist system with their advertising music; the ones who are happy to pander to the masses; the ones for whom business is their main drive and music simply a means to make their fortune. Failure to compensate those whose work is more specialist, more confrontational, more subtle, more challenging, is an act of complicity in the silencing of social and political debate. Though democracy won’t allow for musicians to be gagged, it can still price them out of the market.

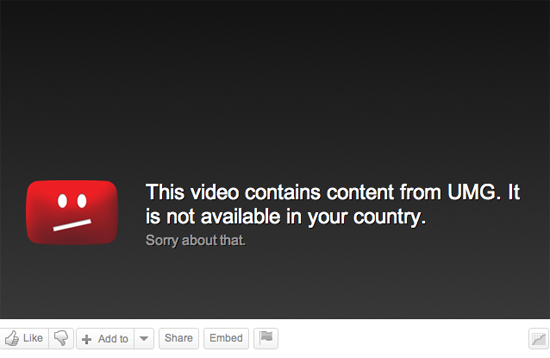

Illegal downloading and its methods are here to stay – foolishly encouraged by the industry’s increasing practise of giving away music – at least until such point as people’s appetite for music, delivered when and how they want it, can be satisfied in an affordable, unproblematic fashion. But making music is work, however prosaic that sounds, and the fact should be respected. The technology to monetise it exists: subscription models like Spotify are well established and increasingly popular. To date, however, Spotify is only available in a limited number of countries while the industry fights for higher royalty payments, and similar arguments continue elsewhere: in Germany, for instance, most legitimate promotional music videos on YouTube have been inaccessible for well over two years while the country’s Performance Rights Organisation, GEMA, negotiates terms. The battle is understandable: Spotify’s payments to rights owners are infamously poor, YouTube’s not much better, and some artists might argue that they’d rather their music be downloaded by genuine fans for free rather than used to enrich a new breed of parasites getting fat off their work. But the longer the industry continues to cling to old-fashioned values, the more people gravitate to illegal sources that are reliable, uncomplicated and modern. It’s an extraordinary situation: in a roundabout fashion, the wider industry is inadvertently preventing fans from legally accessing music in the manner they’d like to, and which technology has facilitated, while blaming them for stealing because they’re not so wild about the systems that have so far been approved.

Whether the industry likes it or not, music is now like water: it streams into homes, it pours forth in cafés, it trickles past in the street as it leaks from shops and restaurants. Unlike water, music isn’t a basic human right, but the public is now accustomed to its almost universal presence and accessibility. Yet the public is asked to pay for every track consumed, while the use of water tends to be charged at a fixed rate rather than drop by drop: exactly how much is consumed is less important than the fact that customers contribute to its provision. Telling people that profit margins are at stake doesn’t speak to the average music fan, but explaining how the quality of the music they enjoy is going to deteriorate, just as water would become muddy and undrinkable if no one invested in it, might encourage them to participate in the funding of its future. So since downloading music is now as easy as turning on a tap, charging for it in a similar fashion seems like a realistic, wide-reaching solution. And just as some people choose to invest in high-end water products, insisting on fancy packaging, better quality product and an enhanced experience, so some will continue to purchase a more enduring musical package. Others will settle for mp3s just as they settle for tap water. Calculating how rights holders should be accurately paid for such use of music is obviously complicated but far from impossible, and current accounting methods – which anyone who has been involved with record labels can tell you aren’t exactly failsafe – are clearly failing to bring in the cash.

The industry has also failed to acknowledge the fact that the concept of ownership is largely redundant: people want access on demand, and many no longer want to pay to own a limited number of records forever when they can move on to the next one in seconds. They don’t want to shell out the same for a song that they once did because the music is now sadly disposable: they may never listen to it again so its value to them has been reduced. There’s no longer any point in asking why this is: it just is. In addition, the question as to why a download should cost much the same as a physical product has never been satisfactorily answered and has further undermined trust between the provider and the consumer. The net effect of this arguably vulgar focus on cash is that people now expect music to represent better value for money, and far too often the music industry has failed to justify its prices. The fact that they’ve spent recent years brutally discounting their product underlines the public’s opinion that they were charging too much in the first place, and the countless stories of artists trapped in dubious contracts have made people thoroughly unsympathetic to the business’ complaints.

Perhaps the industry’s in league with this too, its eyes on a more insidious long term goal: after all, big business doesn’t work for the people. The people work for big business. If a world can be created where most musicians simply can’t afford to exist from their work, then that’ll leave the ones who do exactly what they’re told thanks to the promise of fame and fortune. It’s already happening on TV (especially talent shows), in movies, even in bookstores: the slow, pernicious silencing of alternative perspectives buried beneath a storm of loud, obnoxious yelling about nothing. When Bill Hicks berated the anaesthetising effects of cultural deterioration in the USA twenty years ago, the only thing he failed to warn us was that this would spread across the globe. “Go back to bed, America, your government is in control. Watch this, shut up, go back to bed, America. Here is American Gladiators, here’s 56 channels of it! Watch these pituitary retards bang their fucking skulls together and congratulate yourself on living in the land of freedom. Here you go, America – you are free to do what we tell you!” Except next up, it’s The Black Eyed Peas, Rebecca Black and – oh, let us briefly titillate you – Lady Fucking Gaga.

“When you’re in Hollywood and you’re a comedian,” another tragically deceased stand-up, Mitch Hedberg, joked, perhaps bitterly, “everybody wants you to do things besides comedy. They say, ‘OK, you’re a stand-up comedian. Can you act? Can you write? Write us a script?’ It’s as though if I were a cook and I worked my ass off to become a good cook, they said, ‘All right, you’re a cook. Can you farm?’” This is the position in which our musicians now find themselves. They’re expected to multitask in order to succeed. Their time is now demanded in so many different realms that music is no longer their business. What we can increasingly expect is a conveyor belt of smug accountants living a pop star’s dream, performing aggressively marketed, lowest common denominator, unchallenging dross.

The problem is, it’s not really the industry that is being cheated. It’s the artists and their fans. People get what they pay for, but – whatever the industry claims – most fans know that. They just don’t want to hear the businessmen fiddle while the musicians are being burnt. Revenues are unlikely ever again to reach the levels of the business’ formerly lucrative glory days, but in its stubborn refusal to recognise that both the playing field and the rules themselves have been irreversibly redefined without their permission, the industry is holding out for something that is no longer viable. Lower income is better than no income, and the industry has surely watched the money dwindling for long enough. Musicians, meanwhile, are being asked to make more and more compromises as they’re forced to put money ahead of their art on a previously unprecedented scale.

The battle to prevent filesharing has been lost, rightly or wrongly, but there are still plenty of honest folk out there willing to exchange cash for music in one form or another, and it’s not that they don’t want to recognise its value. It’s that record labels no longer know how to earn their money, and can’t decide how to let them pay for it anyway.

Thanks to Paul Resnikoff (Digital Music News), Tracey Thorn, Ewan Pearson, F.M. Cornog, Mac MacCoughan & Jimmy Webb for their time while researching this article.