Thursday night, two days after the twin towers fall I’m walking home from band practice, blissfully sated, crossing a junction, aware of some pointing and jostling of elbows in the boy-racer to my left. Engine revs as I cross, laughter. Older fears than the lads in the car, rise up inside. Make it to the kerb, ambler gamblers off down the ave, a half-second of relieved silent self-mocking, then some real loud mocking out the wound-down window. The word shouted from shotgun is loud and greeted by much back-seat guffawing. The word is "bomber".

Now where should the camera go, whose story warrants chasing? The doddery old twat on the side of the kerb thinking ‘what?’ Nahh, course not, follow the hate, follow the haters, the ‘questions’ they ask. Always deal with the ‘issue’, the ‘problem’ of us being here, the gift of your tolerance our only redemption. Doesn’t matter, those lads probably forgot about that high-larious moment pretty quick. A decade on I haven’t. You never do, you keep every single moment like that locked in raw, to be returned to and prodded to feel the hit, an endlessly renewable graze on your future. I’ve had cameras swooping around me my whole life, as a way of dealing with routine, and as a way of dealing with moments when you’re young and you see your kind attacked, abused, laughed at, on streets and on the screens you hide in to avoid the streets awhile, and you’re too young, and too scared, to step in and change things. It confuses you, angers you, fucks you up, and at a young age can turn you a bit stroppy and inward, never leaves. And because it happens for my ol’ generation at a young age, it’s important. It’ll keep happening, and even though at my age now you greet that with a shrug rather than a snarl – the odd street-level bit of outright abuse, the trains and pubs you still avoid – it’s part of you. Hello. My name’s Neil Kulkarni. Astronaut, priest, problem to myself.

I’m Indian but I’m Cov born’n’bred, weak in the arm and thick in the head. My name is the colour of Krishna’s skin, a shadowing blue as we face down another decade, a darkening blue as my blood thickens and coagulates and seizes up in the dim presentiment of how the likes of me, made up only of the spaces in-between cultures, are a dying breed, stranded by our dislocation. That dislocation increases with age, even if the future generations of people who are going to call themselves proud to be British will be similarly composed of phantom solidity, but in numbers will find STRENGTH from that non-alignment with the monolithic, the strength us nervous pioneers had to keep locked up, sipped from in those moments alone after the freshest latest despair. When we didn’t have the advantage of numbers, our music made us strong, gave us voices upon voices, calling us back, pushing us on.

On this island so ripe for invasion, so needing of overthrow I’ve been watching you all my whole life, fascinated by the spectacle of wholeness, white skin, black skin, so pure and sure, so past being a laughingstock, so distant from my fear and resentment. The pop you made, made me, but now it’s in glut and decline I look around for a likeness and find nothing. No wonder Asians wanna blow shit up if there’s no pop around to suck up their questions and anger and make it art, if in fact their idiot teachers and gurus and imams are teaching them the lie that the prophet hates music, that god disdains the godlike, that poetry can’t save your life, that music can be tethered to something as permanent and paltry as a nation or faith. Dislocated on buses on planes on foot in streets and shops and schools and shop floors that barely-disguised loathing and faint-amusement we’ve been getting since the 30s, through the 60s and 70s that are apparently UK-pop culture’s golden age, amplified post 11-9 to a frenzied tinnitus of native patrician disappointment – if all that rage created in all those Asian hearts can only find reverb in the words of warmongers and martyrs and priests and not artists then no wonder folk wander onto those same buses and planes and shops with pockets full of dynamite. Music stopped me being a martyr. I had PE to raise questions. And songs to remove my need for answers. Songs that tell you life’s a jail. That we’re only alive when lost.

Without them, without the crucial rhizome Marathi song gave and gives me to the reason I’m here, I’d be the means to my end, prone to any suggestions that might ease the anger in my head when all around is condescension and diagnosis and dismissal. Nostalgia is different if your skin’s a different colour. There’s the same emotions, embarrassment, joy, regret, but they’re amped by that queer relationship with your identity which isn’t just about finding out where you belong, but figuring out where your sense of non-belonging can belong, somewhere you’ll be able to set up shop in your own skin. There’s a reason all that UK rap I listened to in the 90s so often sounded like Robert Wyatt, P.I.L, Raincoats, Slits, Kevin Ayers, Richard Thompson, Fairport – because like them it, and me, were searching for a dissident British identity, a Britishness that dug deeper back than the Heath/Wilson models rotated everywhere else, pushed further-forward than the games of canonical reiteration coming out of all that denim and dead skin that was Britpop, created for itself a proudly anti-nationalist British identity closer to your skewed vision of your homeland. Thus I hid, and still oft-hide in a vintage Englishness, in old English books and films and music, not to find comfort but to find a queasy disenchantment with contemporary England that mirrors my own (yes, in a lot of ways I’m the Asian Morrissey). And by the time you’re an adult that fearful retrospect, that weary vigilance, that taste of bit-lips, the bile, the hotfaced cheekburning shameful paralysis of shock (at the shouts and the kids who laugh/spit at you and the day-to-day scorn that still, no matter how imagined, I feel and absorb and add to the inner-shitpile) has been so enmeshed you wonder if you can define yourself without it. Songs can sometimes be the only thing to pull you out of that circle, to remind you that you look up at the same sun and sky and moon as everyone else, to remind you that your mortality is the only thing that will stop the journey, that you’re older than your age and ancient by birth.

That’s the real lasting scar racism leaves– it can get you to a point where you wonder if your identity is dependent upon the hatred that identity has attracted all its life, you wonder if you’re made by racism, and part of you resists the ability of all that hatred to so foretell your future and delineate your fragile sense of self. It makes you a tad mental. It means that everyone tells you your whole life that you’re over-reacting, that you’re being ridiculous, wonder why you can’t just be cool about it, wonder why you’re so horrified when you see the Asians who arrived later than your parents engage in precisely the same kind of brainless resentment of new immigrants that my parents had to battle before them. Racism, and the spectres it sends skittering and shattering across the ice inside you, also means that today’s Tefal-brow talk of ghosts and hauntings rings awful lukewarm in the twitching traumatised tomb my head’s in. What do you do when you don’t know how to not be haunted? When you yourself feel like an apparition of a soul containing a hologram of a heart, too broken by now to ever hum whole again. When those ghosts so whispishly and wordily wended around. have stalked next to you your whole life, have made your insides judder and clatter at every step, lurk round every corner, every street you’ve ever walked down and every house you’ve ever called home? What do you do when being haunted isn’t a construct or a concept or a theory but an everyday reality that keeps you addicted to your alien-ness, secretly dependent on other’s revulsion, the crossed street, the change dropped from a distance to your foul palm, the eyes never lying when they tell you just how ‘tolerated’ you are? Haunted by who you are, by the idea of being someone. I don’t lend vinyl anymore but there’s a song at the heart of this. It’s a song sung by a dead woman, a ghost to her husband, warning him that wherever he goes and whoever he’s with she will be in his heart. It’s soundtracked by vamping keys, insanely heavy reverb, spooked and wracked sound fx and was made in about 1965, (just before Marathi song started being bulldozed out of Indian cinema, just before my mum and dad decide to blow Mumbai for the other side of the world) for the film Paath Laag and is called Ya Dolyanchi Don Pakhare.

Clutching at forest tendrils, trying to remember, just another old romantic trying to feel alive again before the Great Uploading. Today, 29th April 2011, fly your flag England . Celebrate. Reveal yourself. As you continually have revealed yourself. As wonderful. And shameful. Both. Accept it. Shame is easy believe me. Take it. It’s good for you. It’s good for everyone. And the wonder of this isle? I see it all around me. See, there’s a place I keep mentioning that isn’t England or India or quite like anywhere else. The place I love. The place that truly, eternally, made and mirrors me. Hope in the stones. Hopelessness always two steps on but still, an experiment from the ashes, cauldrons round the lake, cranes now. Funny people. And always new people , too mixed up a place to not have a dead strong identity. Coventry. Coventry my home. Coventry my favourite place on the planet, the only place where I make sense to myself, the only place to always welcome me back with supreme disinterest, to vanish my turmoil in it’s own. Always cameras and the clouds are mountains and the grey sky the ocean.

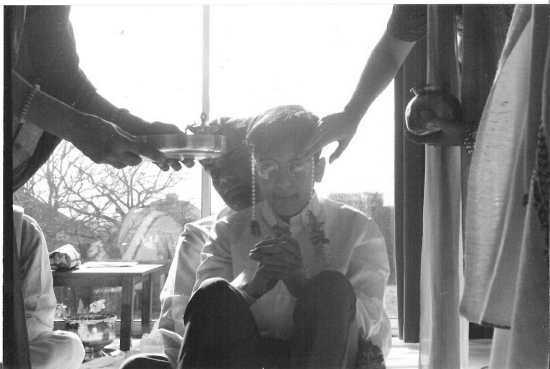

To me, Coventry is paradise. A post-war experiment in social engineering gone feral, a medieval whisper, a madhouse. I’ve been an inmate all my life. There are wings I don’t wander into but that’s the same for everyone. The bulk of the city is deeply and intrinsically cosmopolitan, constantly changing it’s make up, living everyday disproof of Churchill’s lies and Cameron’s snide asides. And no matter where I am, only Coventry makes sense of me, only in Coventry do I feel at home, comfortable. And these things I’ve learned in Cov. Your life is an over-reaction to its roots. Your life has always been bent out of shape by the fact that whatever room you walked in, whatever street you walked down, people noticed your difference. And that difference affects every single relationship you ever have, whether it’s with people, places, or the art that ensues. The only difference between you and the natives is that you’ve been forced to acknowledge the gaps and gulfs and guilt inherent in art, the way that as expressions of personality they’re always expressions of identity whether sexual, cultural or racial. Your blackness, your brownness, are monoliths within you and your life is spent in resistance, reflection, rapture in those genes, you’re a walking wounded cenotaph to notions of integrity and certitude. But in comparison to your own frantic attempts to find out who the fuck you are, the confidence of your white peers in their birthrights and THEIR nation, can feel surer, steadier but never enviable. Because Christ, if you felt at home your whole life, who the fuck would you have ended up as? That grit in yr cells, that reaction against, IS you. And Coventry, as a place of resistance, as dazed dead-end, as an experiment, as good a place as any, suits you from the top of your head to the soles of your feet. My mum’s feet are jungle-hardened, slipped in the unfamiliar snow and broke her arm carrying me, took her to Boots and asked for shoes. Coventry took us in, slow-cooked me in both honest ill-will and serpentine ‘understanding’ and I sit now, in the room my father died in, hearing the trains scream their midnight prayers to the rails, the sirens zero in on their target, and this song makes it plain that in this world, I won’t find a home, only a refuge. Fine by me.

Cov gives me what little pride I have. Proud to have stayed in the wonderful city that gave my wondering parents a home, proud to be from a city whose only constant is it’s constant racial change. Crucially, now that your old project, the industry that your empire took worldwide, that bought me these black plastic lifelines and reels back to my story, is in free-fall and ruins, these exit-strategies and homesicknesses aren’t just my problem any more. Energy and entropy aren’t just battling in withered old shells like me, every generation has it’s own battlegrounds to stumble over. We need to see how we’re going to escape you from the narrowing cul-de-sac that’s squeezing out the dying breaths of Western pop. And to do that you’re going to have to take your medicine, taste the brackish backdrop to your own proud history. Summer’s coming and the factory’s dying. Hear the city grinding it’s eyes open? Hear the birds in the black trees? Pretty soon the world out there will be awake. We need to make plans before dawn. I’m staying right here. You’ve got to move. The next time I speak to you, we will say our farewells.

This was the penultimate part of Eastern Spring. The final section will be on the Quietus next Friday