Whether it’s thanks to a stoner friend or a broad, liberal arts education, most of us have at some point encountered the surrealist film Un Chien Andalou or at least know what those Pixies were on about. But Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel’s eyeball slicing short was not the first surrealist assault on celluloid. That honour normally goes to Germaine Dulac’s La Coquille et le Clergyman, (The Seashell and the Clergyman) produced a full three years before.

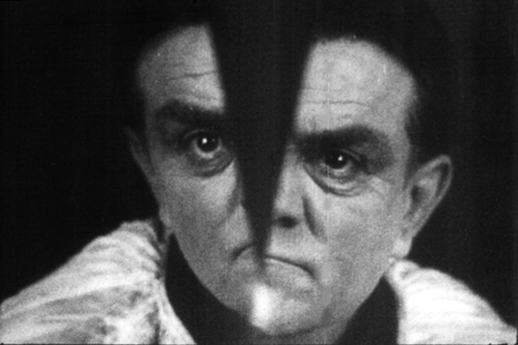

The plot, or rather the driving momentum of the film, comes from a naughty priest who fantasises about killing a General so he can grope the General’s rather frigid wife. In this standard surrealist template, straight out of Freud, it’s fuck the mother; kill the father; sexual liberation = political revolution. The basic dynamic is of course beautifully obscured by lots of fantastic castle-mirrages, heads in bowls, piles of broken glass and, seashells.

The film was scripted by Antonin Artaud, creator of ‘The Theatre of Cruelty’, who was also, originally, slated to play the eponymous clergyman. Artaud’s brand of Surrealism was more extreme and confrontational that that of Breton and Dali: he thought the theatre should infect and transform the audience like a cleansing plague. Needless to say, the film version disappointed Artaud and he is said to have shouted out “Dulac is a cow” at the film’s premier.

Since women were more frequently the passive objects rather than the subjects of surrealist art, it’s interesting to think how a female filmmaker would have coped with the almost dogmatic sexism of her peers. But while in other surrealist art, the men are tormented and feral in their libidinal urges, Dulac paints her protagonist as a bit pathetic – and creepy. Despite Artuad’s complaints, La Coquille in many ways goes further than Un Chien… because here there’s even less connecting tissues between physical locations or even events (no wonder that commenters on youtube were disputing the order of the parts). It’s also punctuated with flashy visual effects and filters which makes it more psychedelic than surreal Its In many ways it’s more like a music video – which is why it has been frequently scored by modern musicians.

This Friday will be the first time it has received a vocal only score by London based singer and composer Imogen Heap. Imogen was kind enough to take time out to chat with The Quietus about the film and her approach to composition.

Could you start by explaining a little about how the project came about?

Imogen Heap: Well basically, a few years ago, Rachel [Millward] who is the director of Birds Eye View, got in contact with me to do a piece of music for a silent movie… a 10 min piece that I wrote on the piano as a compliment to this silent movie. So I did that and really, really enjoyed it, just played piano along with the film and loved it. It was a quick thing that maybe took me a day or two to write and then I came on and performed it. It was so short and sweet but I love this magical thing that happens when you play music to pictures, which I hadn’t really done before. Obviously I’ve seen films but don’t often see films or think about films without their music or music with a film and this magical thing happens when it comes together.

There’s so many times in this new piece that I’ve written when I’d be, y’know, singing along with the characters on the screen and then it’s almost as if at certain moments the film goes, ‘Now this is working’ and you get that shudder and that tells you, ‘This is what’s right.’ It’s easier in a way to write when you have this confirmation of a feeling you get when you see it work and if you didn’t have the picture. I find it reassuring.

Did you choose this particular film. Do you know much about surrealism?

IH: I didn’t choose the film on either occasion actually. I know nothing about about silent movies. I’ve probably watched about three in my life. But what appealed to me was – just recently, I did a film score for a very current collaborative project called Love The Earth with all my fans sending in footage of nature and creating a 32 minute film purely out of their HD footage of nature – and I scored an orchestral piece to this. So I love the dynamic between doing something for a very current project which hadn’t even existed – was kind of bringing itself to life as I was making the music – whereas this film has been around for, well not quite a century. I always like to jump from one project to another which is very different.

But I did watch it and initially I probably thought, ‘This is the strangest thing I’ve ever seen in my life.’ I mean, I’ve seen some contemporary films that are… but this is a very, very odd movie for me and this was the challenge for me to produce something.

Since you’ve obviously watched the film several times, I assume, are there any particular bits that were your favourite or particularly interesting to compose for?

IH: I loved that the film was very graphic. I loved the angles that she chose and I thought, well, in those days, pretty much everything you were doing had never been done before and how she had to think so much in advance of how you were going to piece things together and how hyper-creative it must have been to physically get your hands on the film. That really excites me to examine this woman doing that.

One of the moments I love was the scene with the chequered floor; of him walking with his big, long, elongated coat, walking through the hallway of this buidling that they were dancing in. The image is one of the strongest things I’ve seen and thought it was really stunning so that really stuck with me.

Also I was kind of worried about writing for one bit because it meandered around for quite a long time. The scene when he’s on the boat and there’s this half-water-half-castle thing that he’s holding in his hands. I just thought that kinda went on for a bit! But I’ve never had to do this before so I really learned so many things about how to problem solve. So on that occasion I chose quite a simple choral song – it’s quite melancholic, it’s not busy, it’s actually fairly long and the pauses are very long – and time passes quicker than it would have done if it was something more frenetic.

And when they go dancing – I love that section where you see the women, and the dudes, and it goes to this dream-like section where the dancers… some of them have their tits hanging out and we’re like, ‘Is it real?’; ‘Is it not real?’; ‘Is it is it in his mind?’; ‘Are they actually there naked, just dancing around?’

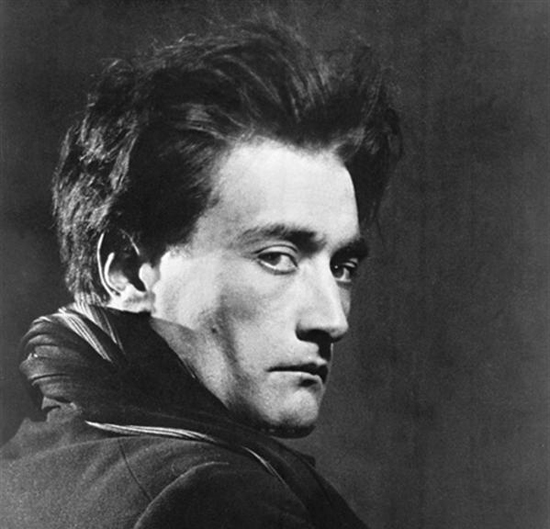

And I loved that whole section where it’s kind of speeding up and slowing down and speeding up and slowing down. In the beginning I was like, ‘Oh right, I can do a kind of waltzing thing.’ But the more that I took the rhythm out of it, the more it became dream like. But I didn’t want to make sense of the film because there was a point, about 15 minutes into the score, when I was kind of realising, ‘I don’t know if I really get this film!’ and I want to know that I’ve done my best to understand what this is really about. So I went online and spent a lot of time researching Antonin Artaud, who wrote the script and discovered that he really disliked it because for him, she interpreted it with too much narrative.

Yeah, that’s an interesting point. She made it into a dream when I think he, sort of, wanted the boundaries blurred. But, y’know, Artaud was crazy!

IH: I took a picture of him into my studio when I was writing. He was quite handsome as well then, when he was 30 at the age he wrote it. I just kind of wanted to know what he was like because I felt bad for him. This was the first time he had a foray into film and he kind of, I guess, realized that maybe this was the thing which was going to continue and represent his life and his work when he was gone. This was because it was visual and would exist after him. And it made me even more angry that he had not been able to realize his idea with someone else’s interpretation. I wanted to try to make the music not follow a narrative and not be descriptive. Sometimes is is very instinctive for me to have actual ‘swoooshing’ sounds – like the sea.

That’s a good point. You’re not trying to be too “literal” with it because it’s very easy to soundtrack it to say, ‘Here’s what’s going on.’ Can I ask why you chose to do a vocal only composition because I know you’re used to working with these found sounds and lots of different textures.

IH: Well, a) because I’ve never done it before and b) Rachel, every year she’d be like, ‘Can you do some music?’ and I kept turning her down even though I really wanted to accept. But I knew how long half an hour of produced music takes and I just didn’t have the time. So I said, this year I’m really going to do it, but I’d just done an orchestral score and I really didn’t want to do another. She said, ‘What about a vocal score?’ and I immediately agreed. I literally thought it would take me a couple of days and but unfortunately, because you’re so limited with your palette you have to be really, really extra-creative and as a result spend a very long time trying to figure out all these tricks of how to make you feel like you weren’t just listening to the same choir for 30 minutes. So it really tested to me to be able to try and keep that interest but I think I’ve managed it!

For more information on Friday’s screening and to buy tickets, click here