Resurrection is both a mystifying and illogical practise, capable of evading all logic of human understanding. The art of letting go comes buried deep amongst raw grief and sadness. Yet we have a choice to celebrate the dead by continuing to live. But under what circumstance can we exonerate those that dare to exhume dead, forgotten, and decaying bodies?

Within a musical context, the current trend of remastering and re-releasing classic material continues unabated. The process is ultimately a licence to print money poorly concealed as a pure, altruistic dedication to the fans. Or the record is now just being released the way the band would have wanted to hear it, but the technology at the time of recording was lacking. Or the technology now is so vastly improved that it brings out the subtlety of the original tapes so a new generation can appreciate it. Etc.

So, what is the accepted length of time before someone can claim a record is a classic? The vast majority of people would perhaps say a record can be labelled ‘classic’ on first listening. Remember how long it took the NME to deem The Arctic Monkeys’ debut Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not a classic? It became almost immediately worthy of inclusion in the top 10 of their 100 Best British Albums List. So why did this young, ‘classic’ British group look to California’s Joshua Homme to produce their last record, Humbug?

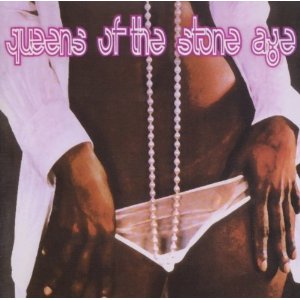

With Queens Of The Stone Age’s eponymous debut out of print for some time now (it was originally released on RoadRunner back in 1998), Domino Records and Homme’s own label Rekords Rekords have united to re-release the band’s record. The word ‘band’ is a little misleading here as, much like Homme’s Eagles of Death Metal, the album’s content was created by only two people. In this case, it’s Homme and Kyuss drummer Alfredo Hernandez (Homme doubles as the bass player with Nick Oliveri appearing only on a distorted voicemail message to close the album). Not simply a straightforward re-release, this polished, updated version features three bonus tracks from the posthumous Kyuss / QOTSA EP, interspersed amongst the original tracklist, and a full remaster courtesy of Brian Gardner at Bernie Grundman Mastering (Garnder also handled mastering duties for the last Homme vanity project, Them Crooked Vultures).

Early fans of the band that already own the album will want to pick up the new version for the warmer and thicker twin guitars that drive the record. Mercifully, Gardner was not drafted into the loudness war, and keeps the overall volume similar to the original and has selected to carefully boost the thin, upper-mid frequencies whilst retaining many of the original analogue dynamics resulting in an altogether punchier sound. Of the three bonus tracks presented here: ‘The Bronze’ takes the form of a late night trip through the desert ripped on acid; ‘These Aren’t The Droids You’re Looking For’ is a chaotic instrumental featuring spacious signature dropped snares; and the dusty tramp of ‘Spiders and Vinegaroons’ is reminiscent of the early Desert Sessions records and all three are worthy of inclusion. If that isn’t a rarity for re-released packages with exclusive bonus material, I don’t know what is.

Those coming to the album afresh might be a little perturbed by Homme’s wavering vocal on opener ‘Regular John’, but those forgiving enough will be rewarded by this worthy document from the band’s catalogue. If anything, it’s quite possible to argue that this is QOTSA’s finest album. Though songs like ‘If Only’, ‘How To Handle A Rope’ and ‘You Can’t Quit Me Baby’ hint at the band’s MTV friendly capacities, there are heavier and more experimental moments that Homme came to harness throughout his career alongside Oliveri before finally losing grip some time after Songs For The Deaf.

The albums that followed after Songs For The Deaf – Lullabies to Paralyze and Era Vulgaris – both displayed a lack of cohesion and an incapacity to reach the harmony of earlier albums, and QOTSA’s live shows sadly became less engaging and less fun with each tour (visible through the Over The Years And Through The Woods DVD). It’s little wonder that Homme finds himself looking to revalidate his early musicianship in order to reassert himself as a snarling, reckless performer and writer. Now a family man, could Homme’s finest Robot Rock moments behind him? In this particular case, it doesn’t matter. Long live the resurrection.