If quantum theory is be believed then there’s no doubt a film about Lemmy doing the rounds in a parallel dimension. On hearing the news he’s been kicked out of Hawkwind following a drugs bust on the Canadian border, our hero books himself into rehab before embarking on a life of recovery, returning to anyone he’s ever harmed to apologise for his evil ways. This goosestepping, 12-stepping totalitarianist is eventually lead into the arms of the Almighty, while the overriding themes are redemption, devotion, and rocking it for Jesus. Lemmy himself isn’t in the film but for sepia footage and homilies from Harry Secombe and the former Archbishop of Canterbury Ronald Runcie. Lemmy Kilmister was sadly knocked down and killed by a VW Beetle careering down some granite steps near Morecambe seafront in 1988. Because only the good die young.

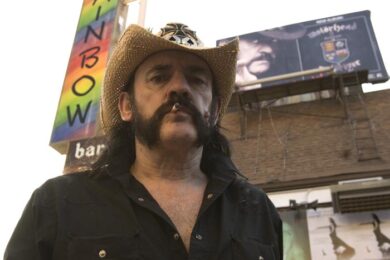

In many ways you know pretty much what to expect from this film, back here in our own bizarre dimension, all about an eccentric expatriate who dresses like a bounty hunter from 2000AD despite the fact he’s 65. Lemmy lives in LA, he smokes a lot, he drinks a lot, he frequents the Rainbow on Sunset Strip a lot, he collects authentic Nazi memorabilia and he loves fruit machines… a lot. He also plays in the loudest, scuzziest rock’n’roll band in the world.

‘People assimilate,’ drawls Joan Jett, disappointed. Lemmy does what he likes though. ‘That’s attractive because people don’t do that any more.’

For all the constant drug and alcohol abuse over the years, he remains remarkably sharp, with an armoury of one-liners for any occasion like an evil Bob Monkhouse. And he sails through life with a myopic determination to indulge in unfettered nihilism. Or that’s what you’re supposed to think.

Lemmy may be a renegade, a one-off, an uncompromising motherfucker at the gates of dawn who takes no prisoners etc, though for somebody who a tired and emotional Dave Grohl refers to as the ‘baddest motherfucker in the world’, you can’t help feeling that leading a life that uncompromising can be a little limiting.

From the early days of rock, through the Beatles and Hendrix, punk and metal, right through to the present day Lemmy has somehow been present, looming in the shadows, one of the few constants in a woefully fickle business, surviving against the odds as his comrades fell one by one, succumbing to the perils of debauchery. He’s led a life like no other, and this film attempts to celebrate that. He’s smart and insightful at times, and yet there seems something sad about his existence too, though following somebody around with a camera all day will do that to them as one of the talking heads in this movie Ozzy Osbourne has shown. Making a fry up, or playing a computer game or staying on a fruity all night or watching endless episodes of Family Guy on a tour bus just doesn’t seem that badass. The Devil makes work for idle hands, and most of it involves sitting on a stall.

Interspersed with Lemmy going about his business is a cast of what seems like hundreds with their own take on the legend. There are funny turns (Scott Ian from Anthrax’s story about finding Lemmy in ‘Daisy Dukes’ is hilarious), and then there are lots of big names who don’t really have that much to add: Dave Navarro, Billy Bob Thornton, Slash, Henry Rollins, Nikki Sixx, that terrifying dude from Twisted Sister. Even Jarvis Cocker makes an appearance. Then there’s Dave Grohl, who is frankly embarrassing. At one point he goes into a rant attacking Keith Richards for still being alive and sleeping with supermodels. It seems that surviving is somehow faking it unless you’re Lemmy.

Kilmister on one hand is self-deprecating. He calls a radio jock a ‘romantic fool’ when he becomes dewy-eyed about the bassist’s Rickenbacker. He says he’s only slept with 1,000 women rather than 2,000, which he doesn’t think is that much given the amount of years he’s been alive. He doesn’t want to talk about drugs, because he’s lost too many friends along the way. On the other hand you get the sense he’s married to his legend, and there’s never been much room for anybody else, or at least until now. His son Paul Idler makes an appearance and the dynamic between the pair is an odd one for the viewer, unused to seeing Lemmy express affection. The most touching moment in the film is when he is asked what is the most precious thing to him in a room that makes Steptoe and Son’s yard look like Wayne Hemmingway’s kitchen. ‘My son,’ he says, as quick as a flash. ‘Because he’s the only one I’ve got’. There’s a moments silence. Then he remembers he has another son but he never sees him.