Cologne had been the birthplace of electronic music, its womb, its matrix; and Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge, realised at the studios of the Nord-West Deutscher Rundfunk in the mid-fifties, was its first acknowledged masterpiece. In the 70s, a certain local tradition would be preserved by two of Stockhausen’s former pupils, Irmin Schmidt and Holger Czukay, who (along with rhythm section Jaki Liebeszeit and Michael Karoli and a succession of unhinged vocalists) were improvising hypnotic locked grooves along to tape loops under the name Can. At the same time, Conny Plank, producer for many of the ‘Krautrock’ bands – and later several British synthpop groups – built his studio in Cologne. In the 80s, with Czukay and Plank still based in Cologne, and the Neue Deutsche Welle taking German electronic sounds into the pop charts, acts like DAF (Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft), who recorded at Plank’s studio, would maintain the Kölnische continuum.

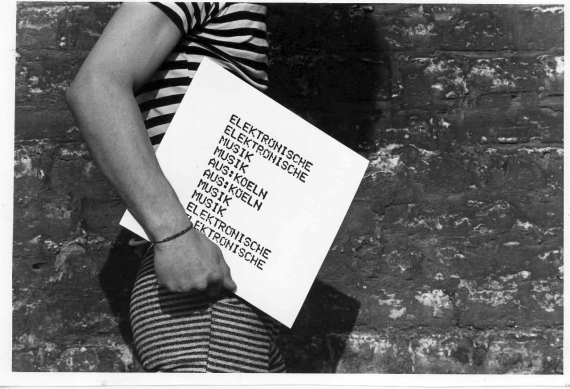

Inseparable from these developments, and yet somehow apart from it all, was the small group of synthpop enthusiasts who gathered in the basement of the Hört Hört record shop to make music under the name Elektronische Musik aus Köln (EMAK). "I somehow fell exactly between two generations," says Matthias Becker, who ran the 8-track studio there, launched the Originalton West record label, and, along with Kurt Mill, Michael Filz and Klaus Stühlen, composed and produced the tracks on the albums EMAK, EMAK2, and EMAK3.

Between two camps in more way than one, EMAK’s name was intended to cock a snook at the presumption of Stockhausen in laying claim to the name Elektronische Musik. One day Becker would write a history of electronic music, and it would be a history not of people, but of machines – of the vintage analogue synthesizers that had so inspired his own music-making. At the same time, Becker and his cohorts clearly felt little affinity with the NDW acts. He dismisses Nena as mere "teeny bopper stuff", claims it was only Conny Plank’s production work that made DAF interesting, and the best he can say for Trio or Andreas Dorau is that they were "funny".

"We tried to weave the influence [of NDW] into EMAK 2," he says, but "it didn’t really work." You can hear it in the simple synth melody to ‘Tanz der Vampire’, which moves almost entirely in intervals of a third, and in its brief ska rhythm breakdown. But on the whole EMAK 2 is the least represented of the three albums on the new Souljazz compilation. "The following album, EMAK3," Becker describes in retrospect as "a more earnest approach to electronic music again." It was EMAK 3 that featured their first ventures into the world of computer music and MIDI, with tracks sequenced on a Commodore 64, hooked up with samples from an AKAI S612. The tracks from this third period, ‘Aranea’, ‘Sein und ‘Schein’, and ‘Traumreise’, stick out for their lush atmospherics, their more deeply layered sound.

"Cologne is not an island," insists Becker, and whilst many UK synth artists were looking east, and dressing in ‘European grey’, EMAK would take their influence, less perhaps from their own countrymen than from across the channel. Amongst the first pieces of electronic music Becker remembers hearing are the early records of Pink Floyd and the first two albums by the White Noise, a project initiated by David Vorhaus in collaboration with his friends from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Brian Hodgson and Delia Derbyshire. The "Special Sounds" (as they were listed in the credits) Hodgson and Derbyshire created for Dr Who and other BBC radio and television programmes, would have a subterranean influence on generations of British electronic musicians. When Becker talks about his love for the music of John Foxx, it is his "special sounds" that he refers to.

Something of the playfulness, as well as the drama, of Radiophonic Workshop music filtered through into the sound of the first EMAK record, particularly perhaps in the sweeping drones and siren pulses of ‘Filmmusik’, which was briefly a club hit in the local area. Becker and his friends would frequent the clubs in Cologne, but he admits: "I mostly did not dance but stared at the ceiling and listened to the music." The experience is documented in the lyrics to ‘Wenn Mr Reagan es Will’, a track whose angular guitar riff and phasing electronic drift ice evoke the Berlin period of Eno and Bowie.

One German musician for whom Becker has nothing but kind words to say, however, is Oskar Sala – a man out of time, perhaps, as much as Becker himself. Born in Greiz in 1910, Sala studied composition with Paul Hindemith and became a master of Friedrich Trautwein’s pre-Moog electro-acoustic instrument, the Trautonium, presenting it to the public for the first time at a concert organised by the Berlin Musikhochschule in 1930. Sala subsequently signed up to three years of physics at Berlin university – knowledge he would put to work in developing variations of Trautwein’s invention, such as the Volkstrautonium, the Quartett-Trautonium, and most famously, the Mixturtrautonium. When Alfred Hitchcock required spine-tingling electronic sounds for The Birds, it was to Oskar Sala that he turned.

Becker first met Sala as a journalist in 1992. For five years, Becker had been writing a column on vintage synths for the German magazine, Keyboard. Two years later, he would arrange for his Originalton West label to re-issue Sala’s classic (1970) LP Resonanzen. "From the first moment we met, I was overwhelmed by the power of this old man [he was 82 at that time] who still was so full of enthusiasm for his music and his instrument, and had such a positive attitude towards life in general" says Becker. "I met him several times during the following years and each time it was like meeting an old good friend. I never will forget the night – must have been in 1994 or 1995, I suppose – when he, Florian Schneider and me had a drink in the lobby of the Maritim Hotel in Cologne at two o’clock in the morning. Talking about the Trautonium, the art of cooking asparagus and life in general. Sorry that he is no longer with us." Sala died in 2002, and without having taught anyone else to play the Trautonium, he carried his expertise to his grave.

The three albums released by Becker, Mill, Filz and Stühlen between 1982 and ’88 represent an important and much neglected chapter not just in the history of electronic music in Cologne, but also in the history of the art school influence on pop music. Most of the friends who gathered beneath Hört Hört were graduates from the local art college, and Kurt Mill, in particular, carried his interest in the Neue Sachlichkeit over into the minimal sounds and arrangements he brought to the EMAK records. As Becker quotes the English performance poet, Pete Brown, finally mocking even himself: "The old art school dance goes on forever."

EMAK is out now on Soul Jazz Records