The War You Don’t See

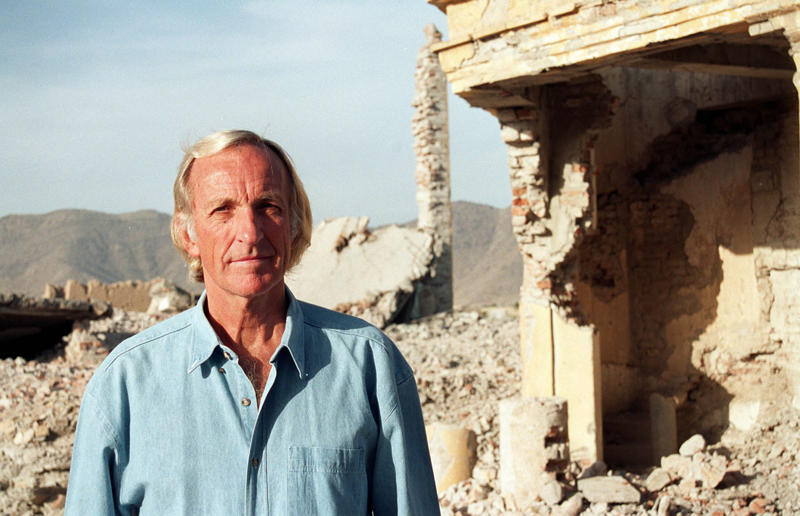

Journalists are a lot like people. They’re either complete bastards – hell-bent on showering the world in right-wing political ideology whilst reaching peaks of sexual glee over the impending Armageddon – or, like everyone else, they’re a bit misguided. The focus of John Pilger’s latest film The War You Don’t See is on the latter type of person/journalist – and more specifically, on how seemingly intelligent and free-thinking individuals (thankfully he doesn’t even bother with the Fox News journalists) make such a balls-up of reporting important news events on various wars. Though this makes for a fascinating exposé of how wars are reported, the expanding vastness of the topic is let down by the narrowness of its criticism.

Pilger criticises the practice of embedded reporting: this is when news reporters are chaperoned round frontline battle scenes by the army. This of course gives them protection and access to otherwise unobservable areas of battle, but the accusation is that their perspective of the war is restricted and what they report is monitored, so their coverage is bias, and what you have is effectively propaganda masquerading as news coverage.

Some of the most successful exposé documentaries often have three quite basic and optimistic assumptions: reveal the truth, or at least the dirty underbelly, of an institution and people will want to act; the problem has a solution; people’s actions can make a difference. Part of the success of Michael Moore’s documentaries is in this simplistic outlook – for which they are flawed and liberating. Even Al Gore’s dystopian present The Unbelievable Truth ended on an optimistic high: it’s simple… here’s what you can do. It’s clear that John Pilger believes the last point, but it’s not entirely clear where the problem of news reporting examined in The War You Don’t See even starts.

In speaking to a number of established news reporters and TV execs, the feeling is pretty unanimous – and was admitted by high profile figures Dan Rather and Rageh Omaar – that journalists weren’t asking pressing enough questions during the recent Iraq war on everything from reported WOMDs to the use of violence on the Iraqi people. But the blanked-faced response was equally universal. We were just reporting based on the information given to us?

So the buck gets passed down to the TV executives and those that head the news reporting. Shouldn’t they go to greater effort to make sure they collect more information to receive a more rounded coverage? Well, again the problem seems to be – as comments from people like Fran Unsworth at the BBC and David Mannion at ITV in the film seem to suggest – getting hold of information.

The question Pilger doesn’t ask, which is strange as it’s central to the whole point of the film, is where does accountability end? How are we in this mangled reportage juggernaut? Pilger’s examination of the structure of this practice is both important and fascinating, yet there are times when his barrage of inquisition at reporters seems somewhat superficial given the apparent size, depth and complexity of these mechanism that guide the route of events to television images.

Most of this issues, as they were covered in the film, seemed to rise out of the demands of 24 hour coverage. As stations need a constant stream of information, they’ll take it from where they can get it. But the Iraqi people don’t have a PR machine, so they can only take that information they have from government and military sources who, as the film shows, carefully select and distribute information. All the news channels can do is question the evidence, yet without evidence to the contrary, they have little purchase with which to make a sufficient rebuttal. Are we to abandon 24 hour news coverage as an inherently flawed medium, or can it be rescued with some light shuffling? This question isn’t answered and no positive alternative is suggested.

Basically, the problem seems to just spiral out of control as Pilger tenaciously grasps to the surface issues of the actual reporting. Of course reporters must be held accountable for what they report, but they surely can’t be blamed if the very mechanism that constrains them is faulty. This is the truly interesting aspect to come out of the film, and also the aspect that never gets a proper investigation. As he shows, government controlled reporting has been an issue in both World Wars and Vietnam, and just about every war in which Britain has been involved. But if you can’t show why this keeps happening, you can’t posit a solution and you’ve merely complained about the symptoms of the problems as opposed to the root cause.

It’s not like the horrendous devastation isn’t being reported. Some of the most disgusting scenes in the film are of American news reports in which the public and reporters speaking with rampant excitement and pride about the sheer destruction of American weapons. If that’s a reflection of mass public opinion, how do you go about correcting it? Showing the destruction would surely only fuel the problem.

Towards the end of the film, the only solution seems to be that nations should stop being of the mindset of which they would want to even have wars which could be then reported. That, however, is a hefty topic by anyone’s standards.

Cuckoo

By far one of the most miserably conceived, poorly executed and lacklustre shambles of a film produced for a good while, this British psychological drama fails in being in any way dramatic, gripping or entertaining. Its attempts to be profound and meaningful are instead dense and clumsy, and Cuckoo eventually falls on its arse, which is a shame as it stars Tasmin Greig, who’s usually great. Yet her confused desperation is palpable as she attempts to struggle free from the constricting one-dimensional skin of her character, Simon.

Right from the off, it’s obvious what the creepy-crawling tension they’re going for is meant to be, yet the first clue in the opening few seconds that this is going to misfire horribly is the awful cod-horror piano music, as if someone had been handed the Halloween soundtrack and told to produce something similar but without the affecting dynamics or any recognisable melody. It tried to say, ‘Don’t sit too comfortably because this is going to freak your paradigms"; instead it said, ‘sit more comfortably because the exit is a long, awkward journey away.’

Polly (Laura Fraser) works as an assistant in a medical centre with the overly eccentric Professor Greengrass (Richard E. Grant). When she starts hearing voices, she talks to her sister, Jimi, who consults Professor Greengrass. The main content of the film then splits into lots of shots of staring at nothing in a dark room and being horrendously patronised by Professor Greengrass’s scientific explanation of hallucination. Most of the time you feel stuck in one long shampoo commercial with it’s over explicit cries of ‘Here’s the science bit!’

These are characteristic of the simplistic over exposition. Every character might as well have massive neon badges with ‘I’m the wacky one’, ‘I’m the analytic one, but I don’t know about feelings’ stuck to their foreheads. All the over-knowing dialogue and dramatised staring gets so uncontrollable that Cuckoo becomes a parody of itself, having the unintended effect of actually being funny. But it’s not terrible or consistent enough to achieve that cult-bad status such that in years to come people will be trying to get hold of it on VHS and giggling along to it at terrible film parties; Cuckoo is just bad.

Loose Cannons

One of the more surprisingly enjoyable movies for a while. Though it sounds like a dour tale of family rifts and sexual liberation against the backdrop of a small, judging Italian town, Loose Cannons is a sweet and quietly absurd story of a rich bickering family. The father, Vincenzo, owns a large business and has hopes for his sons to follow in his footsteps while his bored wife Stefania looks after the home and servants (imagine a parody of I Am Love). Youngest son Tommaso comes back from Rome ready to confess his sexuality to the family, knowing full well it will mean being ostracised by his father and from the business. However, at a large meal with town dignitaries present, his older brother Antonio beats him to it and boldly proclaims he’s gay. Due to the shock of the news to his father’s health and to the social repercussions suffered by his mother, Tommaso feels he cannot let his secret out so agrees to cover for his brother in the family business, while Antonio goes into hiding. Enter the sexy lady and business partner Nicole, with whom Tommaso’s father is constantly attempting to set him up, and you’ve got yourself a good old-fashioned farce. Everyone’s lying to everyone, hiding from someone or is just drunk.

Things get complicated when Tommaso’s boyfriend turns up along with a troupe of very gay friends, resulting in Birdcage-esque silliness as they try to hide their screaming sexuality under thinly disguised macho behaviour. The father becomes borderline insane with excitement at having young men round to chase the town’s women, and his unhinged behaviour mimics his unwavering bigotry and, on a broader scale, take a shot at sexual intolerance in general. The running message of Loose Cannons is made with terrific oddness by the grandmother, in a stultifying ending, that it’s better to go with your heart. And there we go. Nothing original or tremendously exciting, but it’s a harmlessly enjoyable film sprinkled with a touch of the absurd.