The sheer destructive power of the Who scared the shit out of me as a kid. I was but a bairn when I first saw Jeff Stein’s classic rockumentary The Kids Are Alright, which opens with the group miming along to their hit ‘My Generation’ on American variety show The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967, until the song reaches its combustive climax: Roger Daltrey hurling his microphone into the air as smoke-bombs explode about the stage, Pete Townshend hammering his guitar into the amplifiers and Keith Moon ritually destroying his kit before the explosives he’d packed into his kick-drum ignite, temporarily deafening Townshend and setting his hair on fire.

It was terrifying stuff, especially to a five year old for whom Pop Music meant watching Madness goon about with the Phantom Flan Flinger on Tiswas, not amphetamine-eyed art-terrorists causing enough ballistic chaos to visibly unnerve hip presenter Tommy Smothers. Mum’s loud tutting from the kitchen suggested such dangerous recklessness was to be disapproved. However, the way Dad so joyfully hammered the arms of the sofa in concert with Moon’s frantic drum rolls let me know that it was alright to be at least a little thrilled by the auto-destruction.

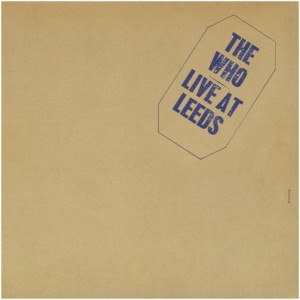

Some curious afternoon a few years later, bored with my Prince and Genesis tapes and rifling through the family record rack for something ‘new’ to listen to, I found Dad’s copy of Live At Leeds, the original six-track vinyl issue, wrapped in faux-bootleg hand-stamped cardboard. I think I paused a moment before lifting it out of the cupboard, the same kind of hesitation a soft lad has before stepping aboard a roller-coaster, or watching a scary movie: flinching in advance of the loudness, the forbidden heaviosity the album promised. But that was also part of its attraction.

Like that kid in Almost Famous, I slipped on the headphones and laid needle to crackly vinyl for my first spin of an album I’d later that evening dub onto both sides of a C90 and play endlessly on my walkman all that Summer, exploring so thoroughly every labyrinthine twist of a sixteen minute jam on ‘My Generation’ that I could probably hum every note to you today. I didn’t know it that afternoon, but I was about to discover what remains, to this day, probably the greatest classic rock album of all time.

As its title suggests, Live At Leeds is that most unfairly reviled of things: a concert album. A format that began life as a cheap cash-in to further fleece the faithful, as rock matured as an artform the concert album became the staging ground for some of its worst and most self-indulgent excesses, for aimless soloing and sloppy performances and muddy recording or – worse – enough studio overdubbing to polish the mess into a saleable but pointless product that sounded like someone playing the album to a roomful of overexcited fans.

Live At Leeds, however, was none of these things, but a perfect artefact that will spoil you for all other rock concert albums. Recorded at Leeds University on Valentine’s Day 1970, it captured a group who’d just spent months touring America where, every night, they played their epochal rock opera Tommy in full, along with some of their hits. Tommy had proved an unprecedented success, a consciously ambitious work perfectly timed for an age where rock was being taken seriously enough for something as pretentious, precocious or portentous as a double-album song cycle (including overtures and undertures) chronicling the life of a deaf, dumb and blind pinball wizard to fly. But while Tommy announced aloud the loftier visions of composer

Townshend, the 1969 album did so at the expense of the group’s natural brute force. In a mid-60s interview clip from The Kids Are Alright, a fevered Townshend can be found repeating the words "power and volume" like a mantra, but The Who had rarely captured their thunderous live din in the studio; blunt, staccato early blasts like ‘Substitute’ and ‘I Can’t Explain’ gave way to the more mannered pop turns of their second album, 1966’s A Quick One, and the psychedelic conceits of 1967’s The Who Sell Out. Tommy, meanwhile, executed its Grand Guignol concept with complex arrangements alongside the occasional power chords, adding French horns and trumpets to the palette, and recasting mad man Moon as symphony percussionist, manning gong and tympani.

By design, Tommy‘s modest orchestrations seem positively baroque compared to the sound of Live At Leeds. If the success and acclaim that greeted Townshend’s "rot opera" threatened to overshadow the earthier talents of the group who’d recorded it, then Live At Leeds was vivid and forceful restatement of those traits, paring their sound back to its purest elements: voice, guitar, bass and drums. In place of Mike McInnerney’s psychedelic-Escher pop-art sleeve for Tommy, Live At Leeds was wrapped in cheap plain cardboard, hand-stamped with the artist and title in the top-right corner to resemble one of a series of bootleg LPs then appearing on the market, illicit live recordings and half-inched out-takes by artists like Bob Dylan, Led Zeppelin and The Who themselves forming a lucrative black

market operated beneath the counter of record stores. While their

contemporaries were grumbling about these stolen recordings – offering rock fandom the chance to hear their heroes’ off-cuts or dud nights, possibly-unflattering raw material that had yet to be okayed for public consumption – The Who responded with the ballsiest move of all: they bootlegged themselves. Live At Leeds‘ faux-Bootleg ruse continued to the labels on the disk itself, with its hand-written track-listing and notes to the pressing plant that any "crackling noises" were "O.K.", and a plea, "Do NOT correct!" ‘This is us, unedited and unadulterated, warts and all,’ Live At Leeds seemed to intimate. ‘We The Who, and we are unafraid and most worthy.’

The thing is, in its initial form, Live At Leeds was edited, with that night’s 33-song setlist (including the obligatory complete run through Tommy) hacked back to a mere six tracks. In this initial form, Live At Leeds is more than faultless. The LP’s excerpted 40 minutes found no space for any numbers from Tommy, nor the majority of the group’s run of inventive 60s singles, nor any extracts from previous albums A Quick One or The Who Sell Out.

On this evidence, The Who walked onstage in Leeds that February 1970 night and played six numbers: three Townshend originals, and three covers. The tracks ultimately selected for release on the album were clearly chosen with the group’s back-to-basics agenda in mind. The covers were performed as loving doffs of the cap to the group’s primordial influences – and all three songs pointedly dated back to before the psychedelic era, to an innocence and brutish simplicity before acid hit rock – but they were by no means respectful. Opener ‘Young Man Blues’ was a cover of ‘Back Country Suite: Blues’, originally penned by Mose Allison, who Townshend acknowledged as a "blues sage". Droll, urbane Allison was a Mississippi jazz pianist and singer whose original recording of the song played its generational ire as hip, ironic pose, revelling in the gap between its fiery rhetoric and the narrator’s laid-back delivery, over coyly studied boogie-woogie. By contrast, The Who played Allison’s drollery entirely straight. Townshend opened the song with a riff as sincere as a thunderclap, before slamming headlong into a wild tantrum of bass and drum tumult; as the scree died away, Daltrey hollered the hook – "Well a young man ain’t got nothin’ in the world these days" – into the vacuum, before Townshend fired up the riff again, and ploughed into another wall of noise. This was how The Who sang the blues: stirring up some revolution between slagheap blasts of trainwreck cacophony. 90 seconds in, however, and the group rocket away from this simple blues, into the first of a sequence of inspired excursive detours.

It’s in these moments that they become The Who of legend: a

remarkable, feral beast of fierce creative discipline, treating

songcraft as a silly putty to be torn apart by explosions of dynamic invention. Though he’s never sounded better than on Live At Leeds, Roger Daltrey’s never been the reason anyone listens to or loves The Who: no, it’s the power trio behind him that make this album, three musicians who all perform like lead soloists, sharing a keen simpatico that keeps them hitting mercurial crescendos together in perfect sync. ‘Young Man Blues’ set the tone for what would follow: rock’s feted opera composers returning to the form’s base elements, and investing them with fevered, high-wire invention. Daltrey’s profane sign off –

"He’s got sweeeeeeet FUCK all!" – bled into a taut blast through

perhaps the most perfect of Pete’s pop songs ‘Substitute’, switching up the riff on the second verse, finding a delicate new tension. Two more covers followed, Eddie Cochran’s ‘Summertime Blues’ and Johnny Kidd And The Pirates’ ‘Shakin’ All Over’; rock’n’roll standards both, the former was a giddy and joyful rumble through the old favourite, Entiwstle clearly relishing his baritone interjections. The latter, meanwhile, invested Kidd’s classic with a sultry, sluggish heaviness, sounding as though Daltrey’s "quivers down the backbone" could plot seismic new faultlines across the plates of the Earth.

Side Two closed out the album with the show’s encore, ‘Magic Bus’

morphing from tripped-out Bo Diddley blues stomp into one final

glorious riffout before the cathartic feedback climax. But the set’s true highlight – and a sixteen-minute extended peak, at that – is Side Two’s ‘My Generation’, which followed the combustive anthem with a thirteen minute detour of riffs and segues and fragments, revisiting themes from Tommy and other Who songs like ‘The Seeker’ and ‘Naked Eye’ between other, less familiar vignettes. What impresses is both the discipline of this heavy-rock pocket-symphony – the way it never meanders, even as it rambles, its passages between brutish assault and pastoral chime obeying some invisible, infallible internal logic – and

its on-the-hoof, improvised nature: they played the song different every time, rearranging some elements and adding new other elements, undertaking this scattershot instant-composition before roomfuls of people every night, an act of without-a-net bravado with the threat of disastrous failure making every step it puts right all the more electrifying.

Townshend’s reputation as a scourge of guitars (he’s sent many into splinters over The Who’s lengthy career) unfairly obscures his guitar herodom. Legendarily cowed by his first exposure to the axe pyrotechnics of Jimi Hendrix, and seemingly disinterested in the blues-worship of Eric Clapton, by 1970 Townshend had distilled a style all his own, a dramatic, dynamic spiel that developed an emotive vocabulary for over-driven and frighteningly loud amplifiers. For just as Link Wray gave rock guitar its growl by stoving a pock-axe through his speaker cone, Townshend proved erudite in his use of feedback and distortion of varying texture and violence. What’s so compelling about Townshend’s guitar is its very physical, kinetic energy, a speeding restlessness. Not for Pete extended solos that showcased his ability to skilfully embroider a blues scale: instead he hurtles at ADHD pace through a slew of tricks and ideas and ace moves, ricocheting between volleys of staccato riff, 10 second blurs of shred, chasm-causing power-chords and blue-veined screams of feedback, one ear ever cocked for the next hairpin turn.

Beside him, Moon’s carnival drums and Entwistle’s buckshot bass plot their own paths, but always hit the same destination. Keith Moon isn’t keeping rhythm (Entwistle’s percussive bass lines often providing that) but rather ever geeing-up the songs’ energy levels with octopus-on-speed drum rolls and sky-caving cymbal splashes. Pete Townshend isn’t just playing the tune (Entwistle’s melodic basslines often proving Big John could achieve more with four strings than many guitar heroes even attempted on six), but plotting new directions for the songs with every windmill-armed kerrang. There are no traditional roles within The Who when they perform live: its every man for himself, or, to grok the more utopian vibe of the times, three separate bodies sharing one mind and purpose.

This is where much of the thrill of Live At Leeds lays: the interplay between these three musicians. With its extended instrumental detours, its multi-part excursions, it anticipates the coming of Prog every bit as much as Tommy did. But Live At Leeds finds The Who unconcerned with finesse, with the precise mathematics of Rock In 7/13 or whatever, delivering something more emotive, more ‘flesh and blood’, more forceful: like in the sequence in ‘My Generation’ where the group retrace Tommy’s ‘Underture’, all tension and explosion, sounding positively elemental. There was something precious and unique bubbling between Townshend, Entwistle and Moon, a magical simpatico that eluded even their most stellar contemporaries. Spin the heavy-medley version of ‘Whole Lotta Love’ Led Zeppelin cut on their bloated-but-intermittently-brilliant 1976 live album The Song Remains The Same, for instance, and you’ll hear John Bonham and John Paul Jones laying down a powerfully convulsive groove for Jimmy Page to extemporise over; on Live At Leeds, however, all three musicians are grasping for that spotlight, ditching the script and improvising off the rails, but still somehow making wonderfully alive, effortlessly coherent music together. It’s not jazz by any means, but it’s entirely free.

In the years that have passed since Live At Leeds’ initial vinyl

release in 1970, subsequent reissues and remasters have restored the 27 missing songs from the setlist. Some of those tracks are excellent: the world could always do with another high-octane dash through Townshend’s Tommy pre-amble, the ribald mini-opera ‘A Quick One While He’s Away’ (even if this version doesn’t match their performance on The Rolling Stones’ Rock’n’Roll Circus); energetic blasts through early singles ‘I Can’t Explain’, ‘I’m A Boy’ and ‘Happy Jack’ further illuminated the Who catalogue, as did obscurios like ‘Tattoo’ or Entwistle’s bruiser of an opener, ‘Heaven & Hell’. Certainly, Tommy never sounded better than when the group ditched the horns and the overdubs and invoked its absurdist oedipal messiah fantasies in the earthy medium of their live show. But listening again to the 2001 double-disk reissue that reinstated the Tommy performance, I have to be honest: it’s pretty exhausting. And the group have seen fit to rerelease the album again for Christmas, in the kind of ultra-super-deluxe package that lets us all know, y’know, we’re not all in ‘it’ together, with replica seven inches and replica vinyl and

the bushel of 14 pieces of replica memorabilia – press pics, posters, invoices for fireworks and a legal summons demanding the return of a guitars, a bass and an amp to Jennings Musical Industries Limited – that accompanied the earlier release.

What’s gotten Who fans all rabid over the rerelease is the

also-included recently rediscovered, restored double-CD of The Who’s performance from the following night. Live At Hull was the show the group originally intended to release, preferring their performance that night, and the acoustics of the larger Hull venue; however, technical difficulties (not least the fact that Entwistle’s basslines were absent from the first reel) scuppered this plan. By transposing the bass parts from Leeds for the first four tracks, studio magic has now delivered us this concert, which adds no further songs to the setlist, and misses out ‘Magic Bus’.

The effect is akin to finishing the best steak dinner you ever ate in your life and being asked if you’d like to eat it all, all over again. And yet, such gluttony is rewarded here: one benefit of the disciplined freedom with which The Who of 1970 tackled rock’n’roll – all vigour, no cynicism – was that they’d play these songs differently every night. It’s a question of degrees, perhaps, poppier fare like ‘Substitute’ differing rarely from the Leeds takes; but on tracks like ‘Young Man Blues’, when the power trio motoring this quartet veer off-road and jam, they discover fresh landscapes of riffing and dynamism, grabbing hold of new ideas in the moment of birth and running with them. It’s electrifying stuff.

Again, it’s ‘My Generation’ that’s the highlight, and again, this is thanks to the song’s lengthy detours. In Hull, they sound looser, more ragged, less gargantuan; they take different paths between the common crescendos compared to the previous night, underlining the fearlessly improvised nature of the epic it had become on the road. Somehow, though, the Hull take isn’t as satisfying, though that could be because I’ve listened to it a fraction as many times; when it diverges from the Leeds version, I’m most struck by how the earlier take’s many random shifts make more sense and hit a more lucid flow than Hull’s various adjunct left-turns.

Certainly, it’d be churlish to discard any of the extra tracks Leeds’ various rereleases have latterly delivered: many of them find the group at their transcendent best, and only increase the set’s value as a historic artefact of what this group were really like at this point of time. The best live albums released by this era of rock mega-stars serve to strip away the surrounding distractions of legend and offer an unerring and often candidly truthful insight into how each group worked. So The Rolling Stones’ Get Yer Ya-Yas Out reveals the group as surprisingly sloppy, swaggeringly rough, but finding an evil groove in

their looseness; similarly, Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains The Same reveals a group who regularly flitted between mercurial genius and turgid self-indulgence (‘Moby Dick’ for fuck’s sake) but who, for all their faults, happen upon moments of rare brilliance along the way.

This surfeit of Who liveage only helps paint a larger picture of what this moment in this monumental group’s story was really like, and thus for the rock scholars among us [pushes glasses up to the bridge of the nose], it’s indispensible. But Live At Leeds is more than a snapshot; it’s a statement, one made

best by the original six-track LP. In a swaggering mere forty minutes, The Who proved that their invention, their power, their genius, wasn’t a chimera conjured by the loftier ambitions of Tommy: strip away the horn sections, the concepts, any pretentions to anything more than loud, dynamic and dramatic rock’n’roll, The Who could still deliver a noise that was inspiring, infested with ideas, and alive with an auto-destructive energy that swung like a dervish among the ashes. And

with Live At Leeds, they offered their succinct epic, a truly

breath-taking act of high-wire rock’n’roll, lightning caught in a

bottle.