The Soft Boys came into my head in Cambridge, in the hot, dry summer of 1976 while punk was being conjured up by a small group of artists and villains in London. My idea was to concoct a tribe of translucent, bloodless man-things that had awesome powers but were largely invisible: stalkers of the hypothalamus, erotic guerrillas that would transform people’s thoughts in a different way from the bludgeoning M.O. of UK punk. The front man would be a robot, for good measure; being the songwriter and lead guitarist I would supply the material and direct the music, while he, Golem-like, would be the cyber-darling of the crowds. I saw The Soft Boys as upmarket versions of Morlocks from HG Wells’ Time Machine crossed with William Burroughs’ slithery boys on bikes. At my table in the Portland Arms, where at the folk club each Saturday I tormented the local bluegrass community with my three-song floor-spot (the MC Nick Barraclough once introduced me as "Cambridge’s answer to music"), I hunched over my Guinness and sketched out my plans.

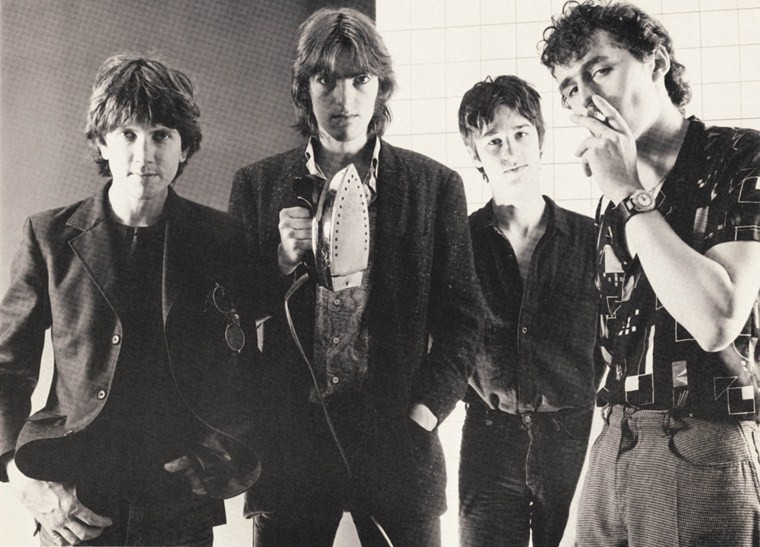

When it came to the actual birth of the band, the reality was a little different. My friend James ‘The Great One’ Smith had pointed out to me some of the great local players who were already on the ladder to professionalism. On his advice, I met Morris Windsor in his dark eyrie, where he gave me some coffee and we leafed through copies of Creem magazine together, not saying much. Then I found Kimberley Rew, appearing through a trapdoor with shoulder-length hair and an ironic (or was it?) grin; he seemed amused that I was me and he was him. Could it have been the other way ’round? From my performance-art perspective, living for my weekly spots at folk clubs, these guys were like Ringo Starr and Eric Clapton, as yet unused. Matthew Seligman smiled charmingly at me across an empty plate in another medieval chamber, and Andy Metcalfe loomed out of the shadows to play bluegrass mandolin at the Portland Arms occasionally.

I could see these people but I couldn’t get at them. The true Soft Boy is almost invisible, only appearing at twilight. But courtesy of Rob Lamb (half-brother of Charlie Gillett, DJ and man of great taste, who sadly died earlier this year) I eventually recruited them all at different points into the band. The early Soft Boys featured Alan ‘Wang Bo’ Davies on guitar and was light in touch; we were crystalline guitars over a nimble rhythm section. Our first EP Give It to The Soft Boys (1977) shows us trying out whatever we thought would work, and on that record it did. When Kimberley Rew replaced Wang Bo, our sound mutated into a ferocious kind of folk-metal, not the easiest of wares to peddle to a UK audience in 1978, which had only the year before been brutally shaved of whiskers and bell-bottoms and converted to punk.

What did we play back then? Bowie’s ‘Station to Station,’ Lennon’s ‘Cold Turkey,’ Cream’s ‘Sunshine of Your Love,’ and Rob Lamb’s ace, the John Cale arrangement of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’. There was always a hard rock element to the SB’s, but we were innocent of marketing at that point. We played what we felt like playing. Gradually my own songs developed: ‘Give It To The Soft Boys,’ ‘The Face Of Death,’ ‘Where Are The Prawns?’ and ‘The Pigworker’. We spent a month arranging a group composition called ‘Hear My Brane’ which was always a favourite. Morris and Andy inclined to The Beach Boys and Steely Dan; Andy, Kimberley and I were big into Fairport, Richard Thompson, and The Albion Band; while I was magnetized by Syd Barrett and Captain Beefheart, but we all loved the Beatles, which marked us out, irrevocably, from the permitted heroes of punk. As we learned to play electric music, we festooned it with harmonies and booby-trapped it with odd time signatures. Meanwhile, Sham 69 were singing "If The Kids Are United, They Will Never Be Divided".

Wang Bo gave way to Kimberley and The Soft Boys spread in a very light film across Britain. Outside of Cambridge where we had incubated, and London where we had first crawled after hatching out, we found ourselves in a bleak and alien land. Huddled at the foot of a slag heap in Grantham (birthplace of Margaret Thatcher) in the drizzle, then watching Kimberley pad through Scarborough in his striped blazer, I wondered how long we could go without being beaten up. Would we be mugged for our cucumber sandwiches and thermoses? After a gig in Sheffield one person clapped and one person told us to fuck off. We finally got an encore in Yorkshire in late 1980.

As we sharpened the guitar sound we started delving back into Steeleye Span and Fairport Convention, whilst picking up the odd droppings from Pere Ubu, whom we supported in autumn 1978. This further polarized listeners; most couldn’t stand it, but the occasional fellow (it was mostly fellows) would become apoplectic with joy and go into spasm. Having spent months and thousands of pounds trying to record ‘Sandra’s Having Her Brain Out’ and other songs of mine from that era, our record company dropped us before the deal was even signed. No one rushed to take their place, so A Can of Bees was released on our own label in spring 1979. Whilst it was a hit with neither the press (apolitical, impenetrable and 3-part harmonies to boot – sorry, lads) nor many of our listeners, it was the best approximation yet of what we were playing at the time, and it did make its way to a swathe of US record shops where young musicians working there behind the counter would listen to it in amazement, sometimes putting it on to clear the shop at closing time. I’ve worked with a few of them since. The Can of Bees tour was a demoralizing experience: long silences in the van punctuated by Kimberley sighing, "Looks like rain."

At this point, Andy Metcalfe left to be replaced by Matthew Seligman, who had played in the band in autumn 1976 for a few weeks. Matthew had a breezy pop funk approach and was folk-proof. The proto-jigs and 9/8 monoliths that I had created for us to play receded into the compost, and I began to work on the more pop end of my notebook. Now I felt like I was writing songs as opposed to just words and tunes that needed making over. The band still arranged the songs, brightening them with harmonies and garnishing them with hooks, but now I was bringing them in whole, line-caught. Whether the others remember it that way is a moot point, but the new songs like ‘Queen of Eyes,’ ‘Kingdom Of Love’ and ‘Underwater Moonlight’ were straight ahead and of a kind with each other, so we finally developed a sonic identity. These were the first songs of ours in two years that people seemed to enjoy.

We were lucky enough to run into Pat Collier, the former Vibrators’ bass player who had just opened a 4-track studio under the railway arches of Waterloo East. Pat shared our feelings about 1960’s pop and loved recording the way the Beatles had: bouncing the bass and drums onto one track, the vocals onto another, and then re-bouncing multi-tracked harmonies as they were recorded so that the mix was essentially done as the recording progressed. Add some spring reverb, plate echo and compression and – voilà! – we had Underwater Moonlight.

Richard Bishop formed the now highly collectable Armageddon label just so he could release our next record. Out of the eye of the mainstream music business, we were developing our own ‘niche market’ and the clubs began to fill up again. Richard’s enthusiasm got us to New York, even. We played Maxwell’s in Hoboken twice in 10 days and at hipster perches like Danceteria and The Mudd Club, with its stage front that rolled up like a garage door. Another foundation stone was laid for the future; I’ve since met more people claiming to have attended those first Soft Boys’ US shows than could possibly have seen us – the audiences weren’t that big.

Armageddon released Underwater Moonlight in June 1980, and it has been released many times since. It was A Can of Bees‘ attractive younger sister; the dissatisfaction that many felt with our first album was melted away by the new arrival. Following our US visit we had the busiest UK calendar ever, a spot at the nascent Goth festival Futurama, and a slew of London shows. John Peel hadn’t previously been a fan but he played a lot off Underwater Moonlight. The Soft Boys were more there than we’d ever been.

But it was never in our nature to be very there. Just as every season contains the seeds of the one that replaces it, so many things were calling ‘time’ on the Soft Boys. For one, Kimberley had been amassing songs since his old band, the Waves, foundered in late 1977: he joined the Soft Boys on the understanding that I was the singer-songwriter, but his frustration was palpable, nonetheless, at having no outlet for them. For another, I hadn’t seen myself as a Soft Boy for a long time and my frontman’s ego was rising to the fore: when Richard offered me a chance to make a solo album I knew that was the way I wanted to go. Matthew too was being courted by other acts, the Thompson Twins among them.

So in February 1981, with Spandau Ballet in the ascension and John Lennon two months dead, the Soft Boys dissolved.

We all had more ‘success’ outside of the walls of fortress Soft Boy.

Kimberley rejoined the Waves, added Katrina, and scored an eternal number one with ‘Walking On Sunshine’. He has also done very well with songs supplied to The Bangles and more recently, Celine Dion.

Matthew joined the Thompson Twins and then Thomas Dolby, whom he had long championed, for Thomas’s pop era. He has played sessions for many from Donovan to Morrissey.

In the mid-1980’s I regrouped with Morris, Andy and others as Robyn Hitchcock and The Egyptians. A decade later I reverted to being a ‘psychedelic troubadour’ (thank you Mark Ellen), with a floating cast of accomplices, often including old Soft Boys.

All of us toured America and got our noses in the rock’n’roll trough in a way that had seemed impossible for the Soft Boys. There have been reunions, even a new record, but the Soft Boys remains, for me, what it always was – a chimera: like a breeze, felt but never seen, from a time long gone.