A die-hard Manics obsessive once attempted to describe their complex relationship with the band to me thus: "it’s like with your family: you can moan about them all you like yourself, but if anyone else insults them you’ll defend them to the death."

This fierce sense of tribalism has helped fuelled the mythology which propelled Blackwood’s glam insurrectionists to stardom, but in the decade and a half since the disappearance of rhythm guitarist and lyrical talisman Richey Edwards, it’s also arguably represented an albatross around their necks. The central conflict running through each new Manics release can be summarised using an analogy from the world of politics: to appeal to the party faithful or the floating voter? If last year’s excellent but unflinchingly bleak Journal For Plague Lovers was a cathartic tribute to the former, then this tenth album is a direct and unrepentant pitch to the mainstream. Or as James Dean Bradfield sings on ‘All We Make is Entertainment’: "I am no longer preaching to the converted, that congregation has long deserted".

Opener and current single ‘It’s Not War (Just the End of Love)’ bursts from the blocks in a headrush of string-drenched bombast; a euphoric blast of FM rock to rival ‘Australia’ or ‘You Stole The Sun From My Heart’. This brash melodic confidence is maintained with the title track, a robust anthem full of richly vivid imagery which sees the Manics caught between a romanticised past and a defiant present ("this world will not impose its will, I will not give up and I will not give in" James sings, to a coda half-inched from Queen’s ‘Somebody To Love’.) Less impressive is ‘Some Kind of Nothingness’, a bloated collaboration with Echo and the Bunnymen frontman Ian McCulloch (the title possibly a cheeky nod to James Dean Bradfield’s flop Kylie collaboration ‘Some Kind of Bliss’?). Presumably conceived as a classic duet in the mould of ‘Little Baby Nothing’ or ‘Your Love Alone Is Not Enough’, McCulloch’s contribution just sounds superfluous, whilst the deployment of that most hackneyed of rock clichés, the gospel choir, merely serves to drown out a potentially stirring melody.

No matter, though, because the next two tracks are uber-pop gems, as commercial as anything the three-piece have recorded to date. ‘The Descent (Pages 1 and 2)’ is a giddy psychedelia-tinged stomp which channels both ELO and Bowie, while ‘Hazleton Avenue’ is a Motown-inflected nostalgic reverie which harnesses the melody of ‘Song For Guy’ by Elton John to the riff of ‘It Ain’t Over ‘Til It’s Over’ by Lenny Kravitz and somehow still manages to sound like quintessential Manics. The band have frequently railed against indie snobbery, but it’s still something of a surprise to witness such shameless pillaging of MOR influences. ‘Auto-Intoxication’ veers into more familiar territory, a tautly-constructed and sonically adventurous rumination on social breakdown driven by a menacing motorik beat.

As befits a man hitting his 40s, Nicky Wire’s twin lyrical themes on this album are a misty-eyed nostalgia for a past slipping beyond the horizon and a disillusionment with the drudgeries of modern existence – specifically the internet (‘A Billion Balconies Facing the Sun’), the liberal-left elite (‘Golden Platitudes’) and meaningless corporate sloganeering (‘Don’t Be Evil’). Wire’s transition from angry young man to grumpy old curmudgeon has been effortless, without apparently feeling the need to try blissful mid-life contentment on for size. His righteous polemics are amplified by some of James Dean Bradfield’s most muscular riffs since Gold Against the Soul. As if to re-assert the band’s Rock ‘n’ Roll credentials, ex-Guns ‘n’ Roses bassist Duff McKagan even crops up on ‘A Billion Balconies…’ to rudder the album’s most straightforward dose of rock classicism. Amidst all this fiery vitriol, the mandola-led ‘I Think I’ve Found It’ feels strangely revelatory; a wistful, gently lilting soft rock anthem conveying sentiments of uncomplicated joy ("I think I’ve found it… and I think I love it").

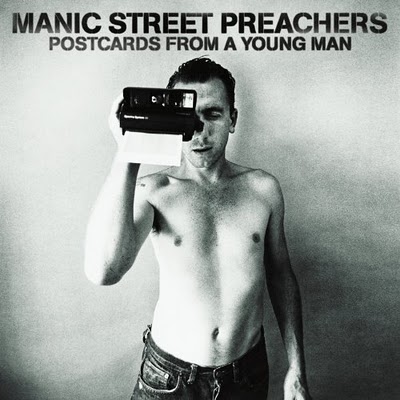

The much-trailed Wire line about this record representing "a last shot at mass communication" hints that this might be the Manics’ swansong, although we’ve learnt by now not to take such rash statements at face value. What is abundantly clear is that, on this form, they retain both the ambition and the fire in their bellies to take on all-comers. The essential contradictions which run through the heart of the Manic Street Preachers are still very much in place, but you get the impression that, ten albums in, they’ve at last reconciled themselves to the impossibility of being all things to all people. Postcards From A Young Man is the sound of a band shedding the baggage of a turbulent past, and in the process thrillingly rediscovering their incendiary spirit.