1978- Rough Trade has moved into manufacturing and distribution. The logical next step is founding their own record label.

Steve Montgomery: Metal Urbain had sent us their first single, ‘Panik’, which we played in the shop all the time and loved. They came over to England and wandered into the shop. They played me a demo tape of ‘Paris Maquis’. Geoff was in New York, hunting out new music and also he was supposed to be having the first real break he’d had since the start of Rough Trade, which he deserved, and I just thought it would be nice if we presented him with our first record on his return. So, after the gig on Friday we rushed off to a studio in Sussex, recorded the track over the weekend, got it all ready, and somehow I was on the station at King’s Cross, Sunday night, waiting to take a train to the boat to Dublin, where it was cheaper to have the records pressed.

Jo Slee: I met Steve at the station cafe, where I drew a circle on a sheet of A4 using a cafe plate and did the ‘artwork’ for the record label. I was still finishing it off about three minutes before the train was due to leave. On the record label outer edge there’s a circle with a jagged rip in it. That was my little joke about Rough Trade being a vicious circle (working ourselves into the ground while trying to change the world).

Steve Montgomery: I took all the money for the record out of the till. We were still a wholly cash organisation. I went the cheapest route and had ten thousand copies pressed up, when perhaps two thousand might have been enough. I think unsold boxes of that record provided foot support under desks for most of the workers up until the company went bust in 1991.

Richard Scott: Everton da Silva was a friend of Augustus Pablo and he walked into the shop one day and asked if we wanted to put out Pablo Meets Mr Bassie. I have a vivid memory of going to cut the record. When we arrived, the cutting man was finishing off his last job – cutting an album of that year’s F A Cup final. When he wasn’t looking, Everton unplugged all the V U meters on the machine, turned everything up full tilt and then switched everything back on. The engineer freaked out – but Everton was right. Played on a good machine that track sounds fantastic.

Peter Walmsley: George ‘Porky’ Peckham often used to cut the records and I think he sometimes couldn’t believe what we asked him to do. I remember turning up with a cassette tape of the Electric Eels single – that was all we had got to work from. I think he used to find it amusing.

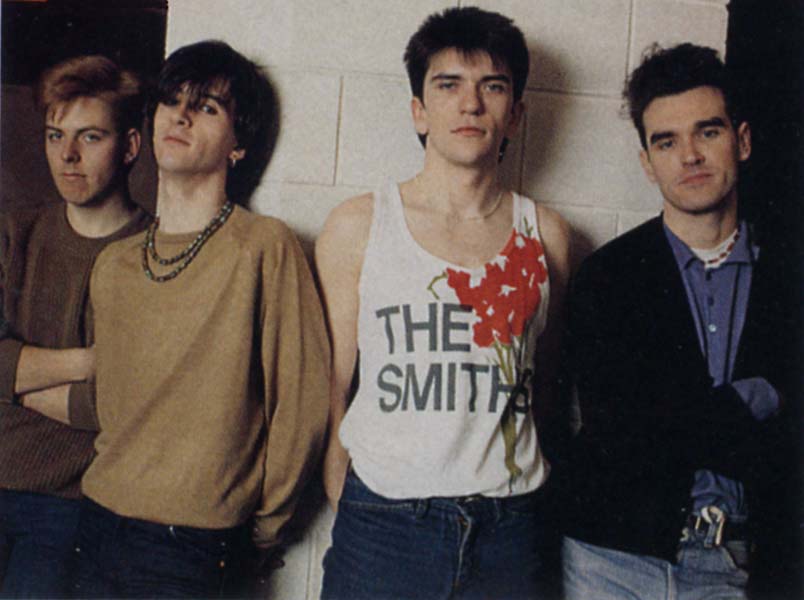

1985- The Smiths are now a huge rock band, a long way from the co-operative ideals that drove their record label. In Europe the fan and some excrement become acquainted, and the talent becomes disenchanted

Mike Hinc: I’d booked them on the European tour. Italy was difficult, not least because the promoter had lied, basically, and didn’t provide what was promised to be provided. He didn’t meet hospitality requirements for band or crew, which would have included hotels, and one gig was meant to be in a theatre and the theatre turned out to be a large tent.

Jo Slee: The next morning I was flying home and they were flying to Spain to play a massive festival. I was in the hotel lobby, sitting next to Mike Joyce, when my anger poured out I said I felt that if I couldn’t do the job properly, I might as well quit. He turned around and said, ‘Well, if it’s not you it will be someone else.’ Coming from the drummer, that told me everything I needed to know. They were pretty arrogant at that point. Too much too soon? I don’t know.

Peter Walmsley: The Smiths arrived in Spain. Their Spanish licensee had done a tremendous job. They were in the charts in Spain and Portugal.

Mike Hinc: We went to a venue where there was a catwalk leading out into the audience, which Morrissey was supposed to walk down. No way. I got the promoter aside and explained that he wasn’t a model and that The Smiths had had a bad experience in Italy. The promoter suddenly stood up tall – he looked like something out of the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, with hair down to his arse – loudly clicked his heels together in military fashion and said, ‘We understand you English because unlike the Italians we are both military nations.’ After that, everything went smoothly on the Spanish tour. I was pleased, if a little nonplussed. At this time, nothing was likely to be good enough for the band, in spite of everyone promising them the world. I think they knew what they were doing – getting themselves into a situation and then poking it to see if it moved.

Geoff Travis: They never specifically said to me that they wanted to leave – that wouldn’t be their way. Even when a problem first became apparent, I didn’t take it too seriously because I knew that they were always surrounded by the utmost chaos and this was likely to be another example of it. They had made a legal move, by sending us a solicitor’s letter, and that in turn called for the correct response. If I had felt that Rough Trade had let The Smiths down in any fundamental way, I’d have probably said, fine, goodbye and good luck. But I was convinced we had done a brilliant job for them – not always in the most ideal of circumstances in the sense that there was always an absence of management, which meant we were often their unpaid management by default.

Jo Slee: It took a lot to make Geoff angry, but when he was angry you knew about it. And in this case he was very decisive. Morrissey demanded of us everything that needed to be done to support their success; he absolutely fought for all we needed to do, and he was right. Whereas Johnny, I think, in those days was susceptible to flattery, Morrissey was different – he knew he was born a queen bee.

Johnny Marr: What Rough Trade and the band were trying to be was the biggest guitar rock/pop band on an indie label with no experience of having worked a big guitar pop band. So, you can’t be too unkind to them. The main thing was that studio time was always at a minimum, and for me that was a bit of a problem. John Porter and I were always leaving the studio at 9 or 10 a.m., really under the gun, having to mix two or three songs, one of which was expected to be a big hit, following another big hit, in the night. Sometimes I felt we were trying to scale greatness while someone else was worried about . . . us getting out the studio the next day

DP Steve Montgomery – manager of the RT store, now a decorator in New York

Jo Slee – former housemate of Geoff Travis, long time RT employee, now an artist and healer.

Richard Scott – employee of RT records, now an artist.

Peter Walmsley – RT employee, now lives in Berlin.

Mike Hinc – booker at All Trade, RT’s agency, now an artist based in France

Geoff Travis – founder, still leads the present incarnation of RT

Johnny Marr- formerly guitarist in the Smiths,

‘Document and Eyewitness- An Intimate History of Rough Trade’ by Neil Taylor is published by Orion at £14.99. It’s far more interesting than you might expect from a history of a shop, though it’s hard to keep a straight face at most of Green Gartside’s delightfully pompous contributions, which make Bolaño’s ‘Savage Detectives’ sound like Richard Allen.