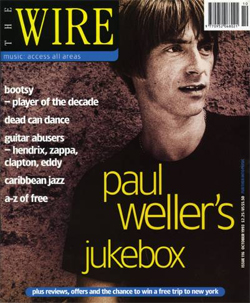

A feature on the musical landscape since the late 1970s, it can become all too easy to take Paul Weller for granted. Indeed, the popular perception of a gruff geezer stuck in some kind of 60s timewarp is one that does a disservice to a artist who has, over the course of his career, challenged himself as much as his audience. This, after all is the man who broke up The Jam – one of the most popular and important bands of their generation – at the height of their fame to pursue new ideas in a new realm. Certainly, the passage of time has served to obscure Weller’s sonic detours with The Style Council in the 1980s, while his early endorsement of house music evidenced not only a then lone voice on the wilderness, but an artist whose keen musical ear kept him excited by what music still had to offer.

2008’s 22 Dreams found Weller rekindling his muse as he explored the musical possibilities of folk, eastern influences and drones as well placing himself and other musicians well out of their comfort zone. The express intention seemed to be to find out what the unexpected results would be. It turned out to be the high water mark of Weller’s solo career to date.

Until now. With Wake Up The Nation, Weller is painting from a bigger palette and his constant striving to push himself has resulted in his most remarkable solo collection yet. It’s still recognisably him but by drafting in guest musicians such as The Move/ELO tubthumper Bev Bevan, session legend Clem Cattini, former Jam bassist Bruce Foxton and, most unexpectedly, My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields, Weller’s tenth solo album is his most sonically adventurous yet. Perversely, rather than stretching himself out again, Weller has compressed the songs into bite-sized two to three minute chunks that create a wonderful sense of urgency.

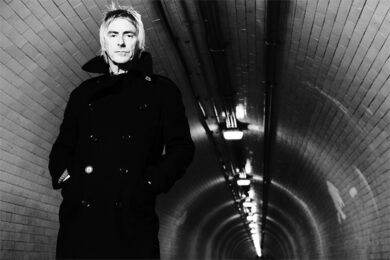

Meeting Weller in his changing room in the very bowels of the BBC ahead of his rehearsal for the following evening’s edition of Later… with Jools Holland, The Quietus is greeted with a hearty handshake and the words you’d least expect to hear from the lips of Paul Weller.

"Alright mate? Here, have you seen that documentary, Dig!? The one with Brian Jonestown and the Danday Wotsit?" he asks.

We sure have, replies your scribe.

"It’s fucking mental, innit?" he replies with a wide grin.

Contrary to his Victor Meldrew of Britrock reputation, Weller is a genial host. Tanned and given to much smiling and laughter, Weller brews up a couple of cups of strong tea and sits down to discuss Wake Up The Nation, the surprising influences behind it and why he feels compelled to carry on creating while avoiding the pitfalls that caught out previous generations of musicians…

What got you back in the studio so quickly after 22 Dreams?

Paul Weller: I was kinda thinking of taking a break and it was only really when [producer and song co-writer] Simon Dine sent me down about ten ideas – just some very loose things that he’d been working on in his studio in Manchester – and I got really excited by them and that was it; I was off and flying really.

You packed a lot of ideas into 22 Dreams and spread them over two discs. With Wake Up The Nation, you’ve packed almost the same amount of ideas into a much shorter time frame. What made you do that rather then expanding yourself once more?

PW: Well, I’d already done that with the double album and it was nice to have the luxury spread all those ideas and influences across 21 tracks but we were very conscious of not making 22 Dreams Part Two. I know that was very successful for us and all that stuff but were really trying to make some kind of departure of sorts. Sonically, Wake Up The Nation is coming from a different place. Some of it was conscious, some of it was just the way things developed with some songs being very short and it’s just the way things turned out, really. But I think there’s an awful – well, not awful – but there’s a lot of music in those two-and-a-half and three minute songs.

Are you worried that perhaps there’s too much information there and people might not stick with it?

PW: Hopefully that’s not the case. I think it takes a few listens to digest it all because there is so much going on but I think that even though there are more experimental edges to the record, it’s still got a pop sensibility. So I think it’s still accessible and challenging but that’s a very good and positive thing.

Some artists are afraid to challenge their audience but you’re not and it’s not the first time that you have, is it?

PW: No, but I do think that I’m in a very fortunate position at the moment. It’s probably harder for bands just starting off [to experiment and challenge] maybe, because they don’t get too many chances anymore, do you? You have to make that first record of yours a success or there’s a fair chance you’re gonna get dropped. There’s no room for development these days unless you’re signed to a Domino or a Bella Union or some independent label.

So I guess it doesn’t really make for a very good climate for creativity, I don’t think, and I think it makes everyone kinda nervous about losing their jobs and their gigs and sort of sticking with what they know whereas I’m – how can I say it? Obviously I want people to like what I do because there’s no point doing it otherwise – but I’m not chasing anything other than making good music. I’ve done all that, do you know what I mean? It’s not like I’m a kid starting out so I’m in a really good position to do what I want to do and I can make what I want to make.

But like I say, I hope people do like Wake Up The Nation and come with me.

The album is characterised by some really interesting influences. You’ve got My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields on there which strikes me as the most unlikely Weller collaborator you can get. How did that come about because I seem remember to you saying years back that you thought the Velvet Underground were the most over-rated band ever and Kevin Shields comes from that lineage…

PW: I’m gonna have to back track if I did say that because I must have said that without ever hearing The Velvet Underground and they’re one of my favourite bands now. I got into their music about two or three years ago through my daughter buying their first album and not liking it and then passing it on to me and I thought, what have I been missing all these years?

So with Kevin and My Bloody Valentine, I think it was through my eldest daughter that gave me some of their stuff and I’d seen him about but I guess I knew his playing and style more through Primal Scream which I really liked – a dissonant wall-of-noise sound. Maybe my head’s in a different place from where it was few years ago, I dunno. But I’ve opened up to so many forms of music and I think the older I’ve got the more open-minded I’ve become and I just wanna hear everything these days because there’s so little time and I just wanna hear as much as I can really.

Keith Richards once said that the older he gets the more intrigued he is as to how far he can go. Are you adopting that approach to music?

PW: I think so, yeah. I think it’s something that’s naturally happening to me but I also think that you reach a certain time of life when you realise how quickly it’s gone. And if the next 10 or 20 years go as quickly then I’ve got to try and do as much as I possibly can. Obviously, you’ve got to have some quality control there but I just think that my mind’s opened up to all sorts of possibilities, really; the more that I listen to or whatever, the more that I see my own possibilities.

I also think that 22 Dreams being a success and people liking that record has been very encouraging as well. When I was making that record I wasn’t expecting anything; I thought it was very, very indulgent and that people were either gonna love it or hate it and fortunately it was the former. But you need those little pats on the back sometimes to push you forward, I think.

I can detect some African influences on the album, particularly at the start of ‘Fast Car/Slow Traffic’. Have you been listening to much of that at all?

PW: I haven’t even thought about that to be honest with you. I have heard African music but I couldn’t talk about it for any great length about it but I have listened to a lot of Ethiopian music and there have been some really great compilations over the last few years. There’s this series called Ethiopiques and there are loads of them and all the ones I’ve ever bought are worth having. There’s a great station that me and [guitarist Steve] Craddock used to listen to in New York when we were on tour – it’s an Ethiopian station – and they just played music all night that was fantastic. So I kinda listened to that but I wasn’t really conscious of that, really. All music’s African really, isn’t it? You can trace it all back to there. Well, most of it is, anyway.

There are some very adventurous pieces on the new album and one that really springs out is ‘Trees’. How is that you’ve managed to pull off a five-piece suite of music in just over four minutes without sounding like a complete cock?

PW: [Laughs] One review called it a ‘mod ‘Bohemian Rhapsody” which I thought was quite smart. I’d like to take credit for that but I can’t; it really was Simon Dine’s idea but it was one of the rare occasions on the album where I had written the lyrics beforehand as most of the others were written on the spot – there was a lot of spontaneous and stream-of-consciousness stuff going on.

But ‘Trees’ was written more like a poem or a piece of prose and Dine had the clever idea of how as each verse takes you through a different character and a different time in that person’s life then the music should change accordingly to make a condensed lifetime which I thought was a brilliant idea and I’m glad it all worked out really.

I’d love to say it was my idea but it wasn’t!

It’s not really an obvious Weller thing to do, is it?

PW: I dunno. I don’t really sit around the studio thinking about what an obvious Weller thing is. I guess that’s part of it; I treat every record as if it’s my first record, really. And whatever you’ve done last time, you’ve gotta forget all that and not do it again and I think my approach has always been like that. Definitely more so in recent years, anyway and I don’t really think about what records Paul Weller should be making, I think about what records I want to make as an artist.

Do you ever get annoyed that Paul Weller the Artist is sometimes sidetracked by Paul Weller the Modfather?

PW: I don’t really give a fuck, to be honest with you. I don’t really mind how people perceive it; I’m only interested to see if they get it. You can’t really stop people’s preconceived ideas, can you? We all do that; it’s human nature. But if people take the time and trouble to listen to the music then it’ll come over differently, I think.

Opinion was split in The Quietus office when this interview came up. The naysayers were sucking air between their teeth and muttering about laddism and beery bonhomie which kinda misses the point…

PW: Well, it’s fair to say that some of it is but quite a lot isn’t. People are more multi-faceted than being some kind if one-dimensional creatures and it’s like what I listen to at home or in the car and I go through a variety of different music. I dunno if you do but that’s just an extension of my character really. There is that sort of laddish side and there’s another side that isn’t that at all.

What’s floating your musical boat at the moment?

PW: I’ve really got into Broadcast. I bought their album, Broadcast and the Focus Group Investigate Witch Cults of the Radio Age just before Christmas and I really, really love that so consequently I’ve gone out and bought all their other records.

I bought some new records yesterday. I bought The XX which liked, a compilation of Celtic folk music which I’ve not heard yet, I bought The Drums. I bought about 10 albums yesterday and it’s the same thing that I always do; I go to buy one or two records that I’ve heard about and then walk out with about ten other ones! And, you know, some of them end up in the bin because they’re shocking and some have been a real revelation. And Broadcast was that for me and it’s weird because they’ve been around for a long time.

What is it about them that does it for you?

PW: Well, they’ve got that sixties thing to them, I think, and there’s a bit of the Velvet Underground in the songs but I like the experimental freeform thing they’ve got going on as well. And I really like the Erland and the Carnival album as well – it’s great.

Neil Tennant reckons that the reason that people like you, Siouxsie, The Fall and Nick Cave are turning in some of their best work of your careers is because you’re all punk rockers at heart. Is that a view that you subscribe to?

PW: It’s something that I could subscribe to but I don’t know if for me, personally, that’s the reason why I’m still creative and need to make music. I think that the thing for me – without naming names and upsetting people – is that my childhood heroes made fantastic music in their youth but they’ve lost it for me after that. They’ve kinda got stuck in one sort of groove and they never see to move on or they become very much like a parody of themselves and all just went downhill and it sounds as if they’ve all lost interest in music and stopped being fans. Maybe it’s because they did so much and burned so brightly in their youth because they were pioneers who delivered so many classics but only up to a certain point.

If anything, I’m very conscious of that and with my age group we’ve had 45 years or more to look back on and learn from; we have all that history to look back on so it’s easier for me in some ways but the people I’m talking about, they were charting a course, they designed the map and we’ve got that to follow now. But I think that a lot of them got very distanced from their audience as well and I’m very conscious not to do that and to keep my feet firmly on the ground.

But you’re adding to that map now yourself, aren’t you?

PW: I’m not too sure what I could say about that, really, but I’m enjoying it though. I may have already said this but I think that there are endless possibilities really. With some of my past work when I got stuck in my own little rut I realised that it’s only yourself that can cut you off from your own possibilities. The more open-minded I’ve become the more possibilities open up to me as well. I’ve a got real ‘the sky’s the limit’ thing going on at the moment. I’m already looking forward to doing the next record but I haven’t got any proper ideas for songs yet but I’m just excited by where else I could go to.

How surprised were you to find yourself working with former Jam bassist Bruce Foxton again?

PW: Well, I’m still adamant that The Jam will never reform; that’s a God-given even though I’ve been asked about it every day for the last 28 years. But as for working with Bruce, it was the right time to do it and it felt right and we did it for musical reasons but we also did it for personal reasons as well. It didn’t feel weird at all – we were just two musicians making a track and we didn’t sit around reminiscing or opening up old wounds. We just got on with the job in hand and it was fun from that point of view. I put a drink in his hand, he got his bass on and that was it really and we both had a good feeling coming away from it but I wouldn’t want to get my old band back together. There’s load of bands doing that anyway. There are bands that split up just a few weeks ago who are getting back together; it’s mental, isn’t it?

But I thought Blur getting back together was good and as long as it works, you know? I think that that country needs a Libertines reunion and I know monetary reasons might be behind that but sometimes these things can work. It doesn’t work for me when it’s not the original members but so much of these things are just a marketing ploy.

But I’m not really one for nostalgia; you just can’t recapture those moments. They’re fleeting enough as it is at the time.

With the passing of your dad and Bruce Foxton’s wife, how much impact has mortality had on your work?

PW: For me – and I can’t speak for Bruce, obviously – I suppose I just I think that I have to carry on to do bigger and greater things really because that’s what my old man would’ve wanted me to do. But I don’t know if it had any bearing on the new record. A lot of people have thought that I might have written him a song on the new album but I didn’t because I think that it’d be a too obvious thing to do really. And if I was going to write something for him it’d be something celebratory like a drinking song or something.

I think getting to 50 a few years ago has something to do with it; that was quite monumental. You know, I’m half a century now! But more than anything is how quickly it’s all gone – it’s like the blink of an eye, it really is. I suppose that if anything, that makes you think, You’d better get your finger out, son. I’ve to crack on because time it short so if mortality does anything at all it makes me want to work as much as possible.

There’s fair amount of righteous anger on Wake Up The Nation that been missing from your work for a while…

PW: Well, I can’t really win, can I? Because when it is in there I get accused of being a grumpy old man – which I’m not saying that I’m not – and when I don’t put it in there I’m accused of being mellow. And I think, Well, what am I supposed to do? But there is a bit of that in the new record. That came about from talking in the studio about whatever the topic of the day was the lyrics coming from those things.

But I do think that it’s a very bland time – whether we’re talking about the media or politics or music – but it’s all seems very homogenised and very safe and I guess it’s just me trying to wake and shake people up and put a bit of fire back in our bellies and stop sitting around like pussies and accepting it all. You know, the fact that one million took to the streets against war in Iraq and the government ignored everybody and still went in.

I think that as English people, we’ve really come along in the last few years to become a modern, forward-thinking race but I think that the politicians and the people controlling us are out of step with the rest of us. And you’re going to change that, I haven’t got a clue; I’m just a musician but I’m still voicing my opinions. That’s what folk music is about and pop is modern day folk music, I think. Music’s always done that. It’s always been there to inform and entertain and that’s what pop music has done for the last 45 years.

Are you trying to shake up other artists to actually say something interesting?

PW: Yeah. I’m still waiting for a wave of new bands to come out and react against what’s going on – politically and culturally. We need a bit of that back in there really. It’s important for young bands to talk to their generation and it’s a tradition that needs to be kept going. There’s a generation out there who are looking for that. These things go in cycles and it’ll happen but it’s a bit overdue.

Wake Up The Nation by Paul Weller is out now