"1989!" roars Chuck D at the beginning of ‘Fight The Power’, which shimmies and seethes with all the controlled, incendiary rage and intent of Public Enemy at their height. It’s set in the immediate future tense, a condition of permanently impending insurrection, as signified by that steampipe loop, not unlike the kettle-at-boiling point squeal of ‘Rebel Without A Pause’ two years earlier. And, of course, it’s a hostage to calendar fortune. Even when it appeared as the concluding track on Fear Of A Black Planet, it sounds unfortunately dated. Yet 30 years on, Public Enemy still feel closer to the Afro-future than whoever or whatever is left of their descendants in 2020.

Perhaps, in retrospect, Public Enemy were a one-band revolution. Subtract them from the cultural equation back around 1990 and you’re left with KRS-1, Ice T’s ‘Cop Killer’, the appallingly scatological Geto Boys and the nascent gangsta delinquency of NWA’s ‘Fuck Tha Police’. But back then, in tandem with Spike Lee, for whose Do The Right Thing was the theme tune, and the political likes of Louis Farrakhan, Public Enemy felt like a full-on, troubling resurgence of African-American militancy. They brought enough noise to make it feel that way, came on like the equivalent of 20 or 30 crews.

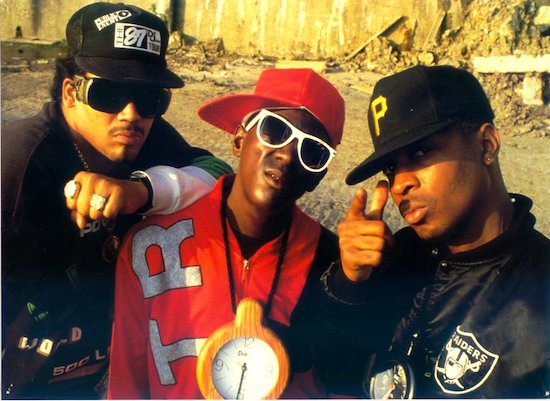

Many people rate It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back as their greatest album but Fear Of A Black Planet is the one that truly catches them at the top of the world. The cover sleeve sees Chuck D, Griff, Flavor and The Bomb Squad poring over a globe as if planning a campaign of pan-continental domination. The concept that drove the album was that of Afro-centricity, which as re-applied by Chuck D meant simply this; all of humanity is of African origin – blackness is the condition to which all humankind will eventually return. The white race was merely an offshoot of that. "Caucasians only make up 10 per cent of the world’s population. So why should the Eurocentric worldview be so dominant?" Chuck D remarked, when I interviewed him in 1990. He dismissed as "irrelevant" the "European aristocratic point of view" and suggested that its extinction was inevitable. Hence the mooted Fear. Public Enemy were scornful of Martin Luther King’s "dream" – they promised reality. "We’re going to come to town with rallies, information and press conferences!" threatened Chuck. It was time to lay low those citadels of misrepresentation, the government, media, Hollywood (‘Burn, Hollywood Burn’ was a keynote track on Fear Of A Black Planet), time for African-Americans to wrest back their destiny.

As well as this supposed historical impetus and radical intent, Public Enemy were embroiled in controversy. White liberals were energised by their emancipatory rhetoric but alarmed by their homophobia ("the parts don’t fit!" reasoned Chuck D, contemplating male homosexuality when I questioned him about this, while he also repeated the story that AIDS was created deliberately as part of a biological warfare project – hence the track ‘Meet The G That Killed Me’). Then there were Professor Griff’s remarks in an interview that the Jews were "responsible for the majority of the wickedness across the globe", which saw him suspended from the group by Chuck D. That said, ‘Welcome To The Terrordrome’ still made the album, with its unfortunate, Christ-killing connotations ("Crucifixion ain’t no fiction . . . they got me like Jesus"). In addition, there were suspicions, in the wake of tracks like ‘Sophisticated Bitch’, that Public Enemy’s attitudes towards women were a touch unreconstructed, and that their emphasis on male dominance of the hip-hop struggle reduced women to the second rank. PE addressed this concern to an extent on ‘Revolutionary Generation’ (‘I’m tired of America dissin’ my sisters’) but it was never possible for the average left/liberal to feel entirely comfortable about PE, though, perversely, this added to their frisson, the un-easy listen they represented.

Still, PE did drop some direct bombs on Fear Of A Black Planet. ‘911 Is A Joke’ saw Flavor Flav drip scorn on the less than rapid response of emergency services to black neighbourhoods, while ‘Who Stole The Soul?’ was an angry post-mortem/inquisition into the commodification, marginalisation and ruin of black popular culture.

PE were white hot in 1990 – and yet, their decline was precipitate and somewhat ironic. I recall, following our interview, Chuck D enthusing about how hip-hop was developing in strongholds all over America ("they’ve even got Atlanta hip-hop!") I nodded politely but, staggering to recall, this all seemed to me to be delusionally sanguine in 1990. He was right, of course. Not only did hip-hop saturate America, it went global. However, Public Enemy themselves were not to share in much of this success. Instead of insurrection, the 90s brought the relatively tranquility and uneventful prosperity of the Clinton years, a temporary End Of History. Nothing much changed for African-Americans, for better or worse. Granted, in 1991 there were the LA riots that followed the acquittal of the cops caught on camera beating up Rodney King but these didn’t prove culturally pivotal. PE were supplanted in favour of gangsta, Gin & Juice, Snoop, Dre and a hip-hop fantasy narrative in which tales of obnoxious murder, misogyny and bling worship were explained away as ‘telling it like it is’. The increasingly, remotely opulent video world of hip-hop and r&b was exclusively peopled by African-Americans but this represented no black planetary racial triumph or emancipation, merely a disinclination to engage with the white hegemony the way PE had. As for Chuck D & co, they continued in the 90s and Noughties to ply their message. But whereas in Birmingham in 1990 I’d seen them play to a largely black crowd (who were very receptive to Chuck D’s Afrocentric message), their appeal dwindled over the years to a point where in 2005 they were playing in Sweden to an audience of 250 – all white.

But – whose loss is that? What was proven by all this? Play Fear Of A Black Planet now and it still hits you like a hip-hop hurricane. The power of the Bomb Squad production team, Terminator X, Hank Schocklee, remains undimmed, gathering up and bundling in loops all the funk and metal flying about in the 80s/90s air, from the squally metal riffs of ‘Brother’s Gonna Work It Out’ to the ‘Funky Drummer’ backbeat that motors practically every track, tangled with ripped off rhythm fenders, restored and looped shards of JB brass, amid a white noise chaos of fragmentary media chatter, phone-in shows, garish incidental music, circuit bent samples hurled at you and impacting like the exploding cathode of a TV set tossed to the street during a riot. This should have happened, outside the speakers and the headphones. For a few years, Public Enemy didn’t just take the temperature, they raised the temperature. It’s simply a shame others didn’t rise with them. That was what time it was, that’s the time it is now. Never mind some of the bollocks they talked, PE were essentially right. Fight the power in 1990, fight it today.