"In our ruthless search for prosperity,

We become the tools of our own oppression,

Forming the backbone of a society

That thrives on mass division."

"From enslavement

To obliteration . . ."

It was a big day for Napalm Death. John Peel’s producer, John Walters, had called drummer Mick Harris at his parents’ house in Birmingham to ask the question every up and coming band wanted to hear: whether the band could come down to London to do a session. They knew that Peel had been going crazy for their debut album Scum, and holding the DJ in no little reverence, they agreed. Too excited to be nervous they looked forward to a Sunday afternoon in the BBC’s Maida Vale studio, and the prospect of a free meal.

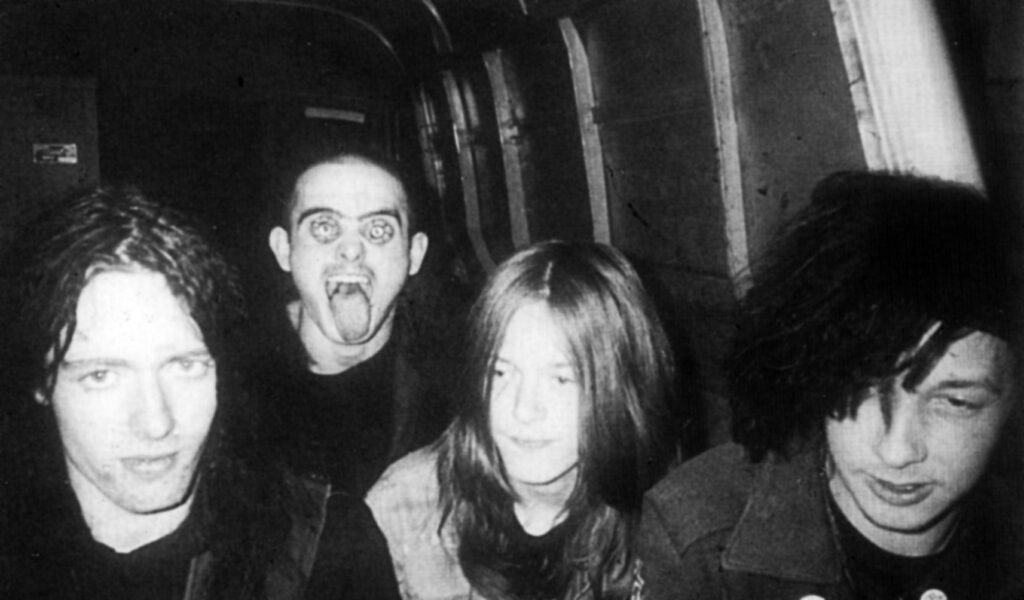

The teenage band – as ever – had to converge on Birmingham from disparate points: bassist Shane Embury came from home in Ironbridge near Telford, Shropshire and stayed overnight at Harris’s house. Bill Steer’s parents dropped him off in the morning (they still wouldn’t let the guitarist travel on his own by train from the Wirral). They piled into the rented van and picked up vocalist Lee Dorrian in Coventry, before heading towards their destiny.

Long-suffering Peel Sessions producer Dale Griffin was aghast. Harris had gamely presented him with the 12 song setlist that the band wanted to perform in their twenty minutes in studio 3, beaming from ear to ear, the hyperactive little shite as ever. But this was not the way things ran, Griffin explained: bands had twenty minutes divided into four slots: A, B, C and D. Yes, a band could get away with five, maybe six songs if they squeezed two into one slot, but twelve was out of the question. Harris had to repeat to yet another sound engineer how Napalm worked: that it would only take a few minutes: their songs didn’t last long. Griffin was perplexed as much as exasperated, but soon relented and stood open mouthed as the band blazed through their set in one take. Music had taken some very strange paths since he had co-founded Mott the Hoople in 1969, but this was something else.

Dorrian and Harris took their positions to overlay the vocals, credited on Scum for "lead growls" and "caveman screams and growls" respectively. Once they started Griffin had to be fast to stop them in their tracks, half-laughing and half-crying he ran out and brought back avant garde punk vocalist Danielle Dax who had been recording in the adjacent studio. They started again, before Dax exclaimed, "You can’t sing like that! You’ll damage your vocal chords, boys!"

Napalm Death’s first Peel session, recorded on 13th September 1987, is the most extreme recording by one of the most extreme bands Britain has ever produced. Because it was for Peel, they made it special.

The shock-and-awe ferocity of its execution is remarkable even now, when hundreds and hundreds of bands since have tried to supplant them. It’s at once a terrifying, hilarious and totally life-affirming encapsulation of their determination to push and push and push the boundaries of rock music; its sheer physicality and visceral, shit-kicking energy attests to a sort of human triumph. Precision and control, calamity and chaos are poised on a knife edge. Napalm Death arrived that day with a bass guitar, a pair of drumsticks and Mick Harris’s trusted Pearl drum pedal (used since his first gig on drums with a band called Martian Brain Squeeze) which he regarded superstitiously as the only one capable of letting him unleash the supersonic beats which made Napalm Death legend. Force of a hurricane, fast as lightning: the art of ‘blasting’.

The first three-track section of the session holds within it all of Napalm’s mercurial madness. ‘The Kill’ starts straightforwardly enough with a searing guitar tone and a three note up-and-down riff before the snare fill kicks it into warp speed: a white noise, sheet metal firestorm overlaid with screaming, syncopated vocal ravages. It lasts less than twenty seconds: musical conventions of rhythm and melody are seemingly destroyed. ‘Prison Without Walls’ is slightly slower, which by any other standard is very fast, but without being flat-out it lurches drunkenly around the beat, Dorrian sounding like he’s sending himself up. But the wayward delivery is abruptly counter-punched by ‘Dead’ (here, sardonically, ‘Dead, pt. 1’), two seconds that razes the opening section to the ground.

Throughout the session, the traditional order of instrumental prominence is upended: the drums dominate, given space to reverberate in the mix. Napalm’s signature blast beats – Harris’s super-tensed peppering of the ride cymbal and alternate striking of the crash – solidify to a terrifying wall of noise. ‘Lucid Fairytale’ even unveils the bass, hardly discernable as anything but buzzing, the distortion more prominent and potent than the melody it adorns; a subsonic abrasiveness that led Harris to dub this new musical form grindcore. The session goes on in squalls and flurries, violently probing the boundaries of what constitutes the acceptable.

And then there’s ‘You Suffer’: notorious for being barely over a second long, here (concluding their little joke)’You Suffer Pt. 2′. Like a stinging blow it comes and passes, and the shock sinks in as it echoes out in the mix. It’s as if one of the denizens of the cave has broken his shackles and dares to look out at the outside world which has hitherto only been reflected on the wall by firelight, and seeing the horror turns and barks one of the most vital questions of the Twentieth Century: ‘You suffer…But Why?’

Napalm Death’s ferocious new form of music developed within a fecund ecosystem of tape-trading and one-upmanship within the punk and metal scenes of the mid-to-late eighties. Its DNA was threaded together by a small, close-knit community that crossed the Atlantic and had roots in Scandinavia. Napalm’s debut album, Scum, captured a sound stretched in one direction by the velocity of punk and in another by the down-tuned heaviness of metal; it was the culmination of an arms race in which speed was the most sought-after weapon.

But grindcore’s visceral intensity is also a product of its era: the years of Thatcherism which presented non-negotiable tenets of governance as opposed to a coherent ideology, pitting working men and women against each other in confrontations which scarred the country forever. Napalm Death is the sound of political thought disengaging from itself, and dissolving into nihilism.

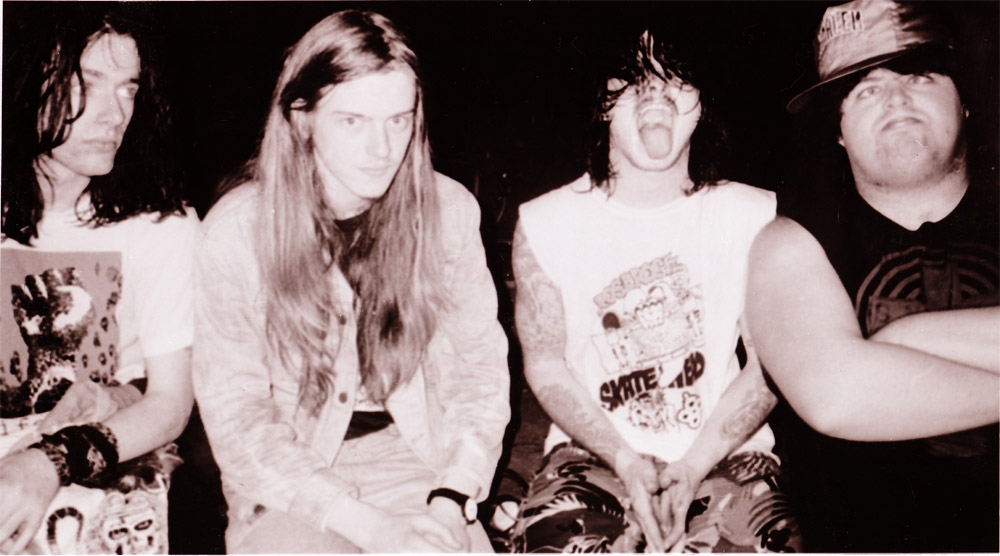

Mick ‘human tornado’ Harris played his first gig on drums for Napalm Death on 18th January 1986, supporting anarchist ‘crust punk’ stalwarts Amebix. Joining vocalist and bassist Nik Bullen and guitarist Justin Broadrick, the floorboards of the Mermaid pub vibrated, bowing under the pressure of the blasts which were met with bemusement and derision. The pub in Birmingham’s Stretford Road, in the poor Sparkhill area of the city, was the furnace of the hardcore punk scene in the Midlands.

Harris used to come and watch Napalm as part of hardcore all-dayers held from midday until late at weekends, convened by promoter Daz Russell. First witnessing the band in the summer of 1985 he saw a group in thrall to the fast, politicized hardcore punk of Chaos UK, Disorder and Discharge (harder, heavier and faster than the likes of the Sex Pistols, The Clash and The Buzzcocks) but also heavily inspired by the desolate, melodic coldness of Joy Division. That would change.

This little guy with the psychobilly haircut intrigued Bullen and Broadrick so much with his velocity that he replaced drummer and founder member Miles ‘Rat’ Ratledge in November 1985. In his bedroom at his parents’ house Harris holed up with Broadrick, his Premier drum kit and a small amplifier, and began a process of pushing Napalm to its limits which lasted for the best part of five years. Harris loved to play fast and craved more speed, more energy, needing to stress the tensile limits of musicality. At the Mermaid he got locked into a week-by-week showdown with the drummer of Nottingham band (and fellow Peel favourites) Heresy: Steve Charlesworth similarly felt the need for speed, but who was soon outgunned by Harris.

Two bands could be heard looming large in Napalm’s new sound: Boston’s Siege, whose 6 song demo recording and 3 contributions to a classic 1985 hardcore compilation called Cleanse The Bacteria (re-released together in 1994 under the title Drop Dead) was thrashy and unwieldy hardcore, and the early crossover of Flint, Michigan’s raw-throated Repulsion, whose January 1986 demo The Stench Of Burning Death (recorded as Genocide) roared and grooved and blasted in tight arrangements rarely lasting longer than two minutes. The demo set the tape-trading underground alight, and Napalm soon lifted the opening riff of the title track to play as an introduction to the live and session versions of Scum‘s ‘Deceiver’.

In a one-bedroom flat further east in the midlands, in Nottingham, Digby Pearson had dropped out of studying medicine to focus on putting out bands that attacked and inflicted noise on the society around them. He called his label Earache Records. Slightly older than the teenage Napalm, in his early twenties, Pearson is a pivotal and controversial figure in the grindcore story. He saw his role as friend first, facilitator second and then as obsessive evangelist for the nascent hardcore punk and extreme metal scenes, pushing tapes of anarcho-punk bands at metal gigs and vice-versa.

He also exploited Thatcher’s desire for a vibrant enterprise culture within a free market Britain. He raised £1000 (mainly selling off his own record collection) so he could be entitled to take advantage of the Enterprise Allowance Scheme. Unemployment had peaked at 3.2 million in 1985; once the government grew sick of counting the growing cost of benefits it made it less easy to qualify for unemployment benefit and then cooked the unemployment statistics, counting only those defined as ‘unemployed and claiming benefit’. Unemployment promptly fell below 3 million in June 1987, and the allowance of £40 a week that Pearson collected was another way for the government to claim that more people were in work and self-employed. In fact Pearson did nothing with the money he was given and it was only the imminent end of the scheme after one year that galvanized him to start putting records out. And Harris kept telling him to come and see Napalm play: "I’ll be even faster next time, Dig…"

Napalm Death recorded the first twelve tracks of Scum in August 1986, using Rich Bitch studios in Birmingham, whilst taking advantage of its 12-8am ‘evening rate’ of half price. The recording cost a total of £120. The songs buzz with Broadrick’s razor-sharp guitar tone, overdriven with an MXR distortion pedal provided by local thrash band Sacrilege. The opening of the album tingles and rings not unlike the opening of Robin Trower’s ‘Bridge of Sighs’ before Bullen roars into the vortex: "Multinational corporations/Genocide of the starving nations." It’s at once mantra, decree, and condemnation.

He rails against the "Forms of escapism/And entertainment" that "disable thought" (‘Caught . . . In A Dream’), fed through a television screen, the ‘Siege Of Power’ within the land and its inhabitants’ minds, rendering them helpless; the "fascist control" that has made its way into everyone’s heads. The sentiments are typical of the anarchist punk mindset: rebels in search of a cause, railing against the system to satisfy their need to lash out against something, anything even.

The songs shift gears from urgent mid-tempo, up to fast, and up again almost impossibly further, to very, very fast. Harris unleashes hell during ‘Polluted Minds’ (which even crams in a rare, dive-bombing guitar solo) and ‘Sacrificed’. Somehow the songs become more agonized – ‘Born On Your Knees’, ‘Human Garbage’ – before one of the shortest songs ever written, ‘You Suffer’, completes the set. Increasingly from the start it feels like there is an overpowering force at work, a chaos which threatens to spill out and destroy the musical order. But this first half of the album is still recognisably hardcore, albeit bolstered with moments of incandescent speed and fury.

The recording was given to Pearson but even at that early stage he knew he wouldn’t be able to successfully put it out with twenty minutes of music alone. But the emerging sound couldn’t tolerate any impediment to its progress. It seemed to have taken on a life of its own: a wild animal straining at its leash and then dispatching any unwilling handlers.

Broadrick was tempted away from the Napalm guitar position to play drums with fast-rising and frequently touring group Head of David in October 1986. According to Harris, Bullen began to arrive to rehearsals extremely drunk, which for the largely sober drummer was simply not good enough. It was a manifestation of a deepening lack of interest in what Bullen perceived as Napalm’s use of speed for speed’s sake. He had been worn down and made way for new blood in March 1987. Harris’s message to them both in the sleeve of the finished album is plain: ‘Keep Your Heads Together’.

What became side two of Scum was recorded in May 1987, on a primitive 8-track, all the instruments miked up live in the studio. Under the aegis of Pearson, Harris had recruited Bill Steer on guitar. Steer had just left school. His main concern was the pioneering death metal band Carcass, formed with childhood friend and drummer Ken Owen and bassist/vocalist Jeff Walker. Their early lyrics dealt entirely with the destruction of the human body, wryly subverting the cartoon-like blood & guts imagery of the genre by rendering it in medicalized minutiae, making it more real than reality. They spawned their own subgenre: goregrind (or even better, hardgore). Steer always perceived his role in Napalm as a hired gun. Harris speaks highly of him today as the "permanent stand-in" who was at the heart of the band.

Harris excitedly showed Steer the new riffs he had been coming up with on the two string guitar he had tuned so he could play bar chords with one finger: condensed, simple, the bare components of music. Steer was a flair player, a devotee of classic rock who adhered to groove, but in Napalm he played it straight and took instruction. His dirty, muffled guitar churns up the bedrock of the second half of Scum, which begins with a song-as-question, ‘Life?’, and blizzards throughout, restless and insatiable.

New lyricist and bassist Jim Whiteley bluntly interrogates everything around him: "Where is your success gained from?/What of the lives you’ve shat upon?" (‘Success?’), "When will you see? We’ll never be free" (‘Parasites’), "Not your problem/ Why should you care?" (‘Stigmatized’), "Is this the price we’re gonna pay?" (‘M.A.D.’).

Rather than aim its sights at amorphous international corporations, it sarcastically baits those who would unquestioningly accept the status quo ("Uniformity/Conformity/How long can you hide the truth?" – ‘Pseudo Youth’) in a world where the fate of humanity itself is sealed and atomic genocide is assured. One question remains at the end of the record: will you "accept the end?"

However, the lyrical content of Napalm Death is problematic, because language itself is destroyed in new vocalist Lee Dorrian’s delivery of the songs. He was so fresh to the material he had one rehearsal the night before to learn it and went into the studio carrying sheets of newly scrawled lyrics he’d worked on with Whiteley. He even had to be cued in during the recording, which contributed to its abrupt, ragged, near inhuman vocal emissions. If the symbolic order of the world is preserved by language, here it dissolves into incomprehensibility.

When he was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2006 artist Mark Titchner cited Napalm Death’s creation of "a language that ceases to function and ceases to be able to communicate in a normal way". For him the album passes from having meaning and a message in the first half to something deeper that functions on a primal level: an emotional engagement that obviates clamouring systems of belief and operates by a new, indefinable set of rules. On the second half of Scum, the incomprehensible rushes in: a nuclear wind of the guttural and the unutterable.

Scum was released in July 1987, a month after the Conservatives were re-elected with a majority of 102. The socialist and anarchist agenda of hardcore punk was wiped clean by Napalm Death’s grindcore. In its sarcastic rebuttals to music and order itself (the second Peel session of March 1988 starts with a version of ‘Multinational Corporations’ so over-the-top it seems to mock the song’s strident lyrical assurance) it behaves similarly to that other wild animal: free market capitalism. It held a mirror up to Thatcher’s stance against state interference in favour of individual freedom.

Napalm Death’s debut emerged after some of the most pivotal years in recent British political and social history. The miner’s strike, and particularly the Battle at Orgreave coking plant near Rotherham on 18th June 1984, had pitted two titans against one another. On one side, the President of the National Union of Mineworkers, Arthur Scargill, a radical Marxist who believed that capitalism produced contradictions only resolvable by a change in society: "I hope that people do regard me as a dangerous man, in the respect of changing society. I’m certainly a danger and a threat to those who support the capitalist system. And I’m very proud to be a threat to the capitalist system and I hope – by being a threat – we’re able to bring about a fundamental change in society and create a new order." The Marxist view of Thatcherism was that it was an ideological campaign, tailored for and by the rich and powerful capitalists, to lord itself over the wretched and underprivileged working man.

On the other side was Thatcher, a Prime Minister who perceived the Marxists’ belief in state ownership to be a form of enslavement: "the corrosive and corrupting effects of socialism". The victim of this clash of ideals was the working class, divided between the police and miners at flashpoints such as Orgreave – torn apart from within. Napalm Death blazed through this harrying of the British social and political landscape. Their sonic assault whipped up the ashes in its wake.

Dan Franklin works for Canongate Books and listens to Electric Wizard

For more information on Loops, featuring essays from top Quietus scribes Kev Kharas and Frances Morgan, and dark lords of the art Paul Morley and Simon Reynolds, click here.