The internet eats my time, and probably yours too. (You’re reading this, after all). There’s so much of it, saying, ‘look at me!’ ‘no me!’ ‘no meee!’ Countless Facebook updates, blog comments to trawl, pages of tweetstream to swim, and all the responses you need to leave people so they don’t think you’re a dick – it gets paralysing.

But even ignoring all of that, all the other news and links and people, there’s still way too much music – and too much good music – out there. So what to listen to? The perennial complaint of anyone lucky enough to write about music in a public forum is of having too much to listen to, too many promos to sift, too many links to click. Music may be infinite – anyone can create and get the word out – but the time to filter stuff isn’t.

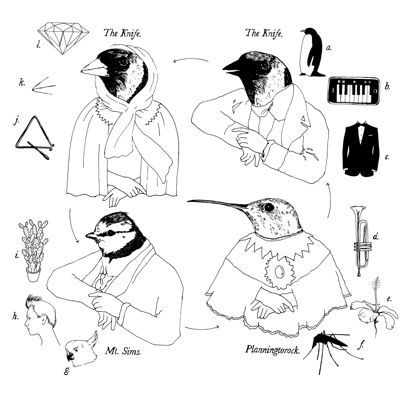

So far, the Knife’s Tomorrow, in a Year – their opera about Charles Darwin, written in collaboration with Mt. Sims and Planningtorock, commissioned by Danish theatre collective Hotel Pro Forma – has gotten mixed reviews, partly for these reasons. Some people love it for its experimentation (The Knife claim to have only seen one opera, a performance of Verdi’s Aida, as research), layers of voices and samples, and subject matter; a lot of people think it’s difficult, overlong, tedious, pretentious. Tomorrow, in a Year demands 90 minutes of your listening time, preferably a few times over, plus some internet research, but for what it delivers, it’s a valid trade-off.

I used to write for Plan B before it closed, and in every issue they used to run a feature called singles club, where a few writers would get together in the office and listen to the month’s singles while having an online chat session in real time. I was very bad at this, because someone else usually had quicker-flashing synapses and faster fingers so they’d be riffing away while I’d sit there just trying to process. Some of the singles that sounded great in that context sounded grating a week later, while some others were slow burners that rewarded patience, but only the eighth time around. But by then, the conversation was over.

So in this environment of constantly churning information, what does it mean to make an album that’s part of a larger project that demands your attention in longer, more concentrated stretches? Or just in stranger concepts and fiddly formats? Over the last few years, to name a few, we’ve seen Dirty Projectors’ cassette version of Bitte Orca, Joanna Newsom’s triple album, the Flaming Lips’ triple album, Fiery Furnaces’ triple live album and self-covers album – even projects like Damon Albarn’s OTT Monkey: Journey into the West opera. (The Magnetic Fields’ 69 Love Songs was a test shot in 2000, but that was a decade ago, when Napster and AOL were too niche to hide behind a spreadsheet.) All of these projects are kind of audacious: they say, this is worthy of your attention, and your concentration, give it here.

Most of these musicians are in their late 20s and older, and came of age in a time when music was listened to and written about in a much slower, earthbound fashion. Distribution channels were expensive and full of friction, and there was also less recorded music around. But creating work that is demanding by length, concept or complexity isn’t some kind of retrograde move.

The last huge moment for triple albums and forays into the full-on operatic, beyond the valley of the avant garde, was probably back in the glory days of prog – at least if you follow the logic of Prog Britannia and similar documentaries. That school of rock history, which tells of old guards overthrown and annihilated by whatever is newer (and therefore better) is a judgement driven by a marketplace that runs on churning up anxiety about neologism and acquisition. That’s hard to play if 1) there’s a near-infinite amount of new music and 2) everything old is available (and it’s also new to a lot of people who might not have had access to it before.) How do you even set up oppositions when the next wave of whatever is already there, and there, and there, all at once? Anyone working now, especially anyone making tricksy albums, is aware of the situation and asking these questions.

Or to get Darwinian about it: how do we select music? What survives, what is fit?

The Knife ask the question by creating work around the guy who asked the question first, and kept asking it. On the Origin of Species was edited and updated several times. ‘Survival of the fittest’ isn’t even Darwin’s phrase, but the philosopher Herbert Spencer’s, added in to the fifth edition. The idea of whatever the ‘fittest’ means is arbitrary. It’s not a value judgement of moral right or possibility; all it means is that something is better equipped to survive within a particular environment or set of circumstances, however crap those circumstances may be. Environmental constraints may be social, technological, or just plain bizarre.

This kind of selection is something Carl Sagan explained in the television series Cosmos, using the example of the Heike crab: a Japanese species whose shell markings sometimes resemble a human face. Generations ago, fishermen would catch these crabs and throw back the ones that looked like they had a Samurai face on their back. Over time, the surviving crabs were those that looked more human, and specifically more Samurai-like; over hundreds of generations, guess what you get?

The crabs that survived did so because they evolved to suit some completely arbitrary ideals made up by some bored fishermen with a bad case of pareidolia. It makes me wonder about how the five-minute darlings of the music blogosphere get there (and where they disappear to). In the New Statesman last month, Daniel Trilling made a compelling argument about Lady Gaga’s suitability for soundtracking the gym. It would be a bit ridiculous to claim that’s the only reason Bad Romance is a monster hit (and he doesn’t), but if that’s a context where a lot of people experience music, it can’t hurt either.

So what if you make a record – and not just a record, but an opera – that calls into question what the parameters of selection should be? We’re humans, and unlike the Heike crabs we have a bit more agency here – we can shape the social systems that push us toward one choice or another; we can decide how we design technologies and how we use them,

Instead of acting in opposition to the bitesize download, Tomorrow, in a Year might be part of a dialogue, asking us to take a break. To stop for a second and think about how format drives function. Why else was the eleven-minute ‘Colouring of Pigeons’ released as the first track from this album? It’s the anti-single. It starts with sparse drums and forest noises. When the vocals come in, each part shifts from vocalist to vocalist, knitting together lines about cocoons and the sky with the lightning and the water", smiling, spoon-grabbing children and connections: “tail-habits-proof". The song spans a vast planet of discoveries before Karin Dreijer Andersson sings about “the delight of once again being home" in a voice that sounds cobweb-creaked with emotion. Another minute or so of vine-swinging percussion follows, which is in turn followed by a further minute of scrapey, metallic e-bow drones.

It’s the kind of song that, four decades ago, would have had chapters. In an earlier interview with The Quietus, Karin mentioned that she was into Laurie Anderson, whose ‘O Superman’ and ‘Big Science’ this song echoes; you can hear the influence in the sluices of violin, and repeated “ah"s. But Laurie Anderson’s songs clock in at 8:27 and 6:25 respectively, and while ‘O Superman’ made it to number two in the UK charts it did so thanks to the help of John Peel, that master crab fisherman. An easier single would have been The Knife’s next track, ‘Seeds’, with its minimal skips and twinkles that could soundtrack timelapsed photography underground or skittery popcorn exploding, hinting at Autechre.

It may be anti-single, but this album is not anti-internet. Other links are traceable, and it’s almost a game to spot them. Tomorrow, in a Year is a few generations removed from the primordial stew of the operatic and the experimental, with stops along the way at minimalism, music concrete and free jazz. Tracks sample birdsong from across the world, or turn to electronic assault: ‘Variation of Birds’ is a squall of dogpiling car alarms. The emphasis shifts from plate tectonics, sonic disruption and observation of huge shifts wrought by natural forces, to songs built on a more specific, human scale: mourning, loss, the wonder of observation.

Throughout, the vocals are often unintelligible at first listen, thanks to operatic singing styles, oblique phrasing, and English-as-a-second-language accents. ‘Upheaved’, about land mass movement, could trace its lineage to Klaus Nomi’s ‘Cold Song’ by way of Diamanda Galas. Each staggered syllable gasps and jags like cracks in the earth, cracks in ice. Lyrics didn’t come with my promo copy, and I had to track them down on Lyric Wiki) – again, deliberate or not, this is another way that Tomorrow, in a Year demands engagement, if not participation (who put those lyrics online, anyway: the musicians, or sharp-eared fans?).

The songs about Darwin’s letter to Henslow about daughter Annie and the box of her keepsakes Darwin kept after her death by scarlet fever, aged ten, and the mentions of wife Emma, known for her patience and care for the ill, including her husband and sister – those who were all too human and fallible, but helped to survive – and Erasmus Darwin (which could refer to either Darwin’s intellectually curious physician grandfather or several later descendants) don’t presuppose knowledge; they demand a nose around Wikipedia. It’s not pretentious to tell stories about things that are a click away; it’s lazy not to click.

Better yet, the whole thing’s released under a creative commons license, so anyone who wants to mix it up can, another reward for listening, and maybe a way for this album to spread seeds of influence further. You can be observer and selector, everything is here to unpick, and twist into new things – but Tomorrow, in a Year demands you step back and slow down to do it.