Superficially, one could be tempted to align the music of arcane avant-noise instrumentalists Wooden Veil, an art-collective from Berlin, to that of the post-rock variety. However, that would be a facile comparison as Wooden Veil manage to harness a compelling degree of conflict in their often tumultuously mystical sounds which elevates their music above the more proverbial recordings of the aforementioned genre.

Whether it be in the menacingly distorted, death jazz feedback and tribal drumming of the epic 12 minute track ‘I Love You So Much’, which uses vocal and instrumental carnage as a metaphor for desire, or ‘Wooden People’ which sounds like one is being dragged through a waterfall backwards while hearing a foreign language for the first time, their music holds a primal primacy which is arresting.

What also gives Wooden Veil’s sound its magic is the ability for copious experimentation to occur while a smidgen of rhythmic structure remains so that the sound teeters on the cusp of sonic apocalypse, never quite cascading into it.

The Quietus spoke to the band’s Christopher D Kline about topics ranging from the enormity of nature to ceremonial balloon explosions.

Why did you call yourselves ‘Wooden Veil’?

Christopher D Kline: For each of us the name means something different; to me I always imagine a veil being woven like lace out of wooden thread all wound around bobbins… a kind of impossibility. This sort of allows us to let Wooden Veil create itself, and we’ve found that it really does go where it wants, manifests itself how it will, somehow out of the control of any of us.

Your sound is so diverse, like psychedelically industrial music for nomads, as if urban technology has clashed with archaic rural practice and the results were Wooden Veil’s recordings; how would you describe it?

CK: We had a real problem trying to describe our sound because it comes so natural to us, and all of us come from very different places and situations and influences, so we decided to ask friends to describe it instead. Usually the comparisons surprise us… we’ve been compared to Jodorowsky films, Shinto Kagura music, The Residents, Yves Klein, Joy Divison, The Vienna Actionists, Immortal, Moroccan music, Stockhausen, Amon Düül II, Gregorian Chant, Portishead, Swans, which are all great, but who we never would’ve noticed as influences. Most of our descriptions, like yours, have to do with another time and place, another way of being and living. We don’t really think about it, just let it form itself.

You are a collective that ‘creates a microcosmic world which only Wooden Veil inhabits’ with its ‘own symbols, clothing, food and shelters.’ Do you feel that you have an anarcho-primitivist aesthetic?

CK: There is certainly a primitive element to Wooden Veil in the way we try to get to the root of the abstract vision we share, generally eschewing musicality or academic nuances unless they’re really elevating that vision. But our aesthetics are also disposable, something we wish to hold, not be held by, and so they’re always changing. I don’t think we’re harboring any romantic delusions about hunter-gatherer life or a "simpler" time, though our superstitions and beliefs may be more similar to another age when these things were more nebulous.

Half of your song titles possess links to natural imagery. Indeed, your music would in many ways fit an eco-paganistic soundtrack. Several of your videos occur outside. Do you harbour a strong connection with the natural world which you like to convey artistically?

CK: I suppose each of us in the group have a different connection with nature, but most likely not a very different one from other people who live in a city. There’s a need to get out and there’s also a need for that quietness, that lurking potential energy which you feel in a forest or looking at the ocean. There’s this serenity we take for granted, but also the knowledge that this gigantic thing can come in and just destroy you, destroy whole cities. I think that being in nature has a way of putting things in perspective which things like watching the news just can’t accomplish. You might see disasters and death and starvation in the newspaper, but then you continue on, read your horoscope, check the weather, do a crossword puzzle. It’s just information, even if it saddens you. But spending time out in the woods, sleeping there, can bring the true fragility of things right into your face, the sort of terror and chaos that goes along with beauty.

We don’t really try to convey anything so tangible, but connections are always there slinking around in the shadows.

All of your tracks seem to have a sinister quality to them, whether they sound child-like (‘Moon and Hamburg’) or visceral (‘Shiverings’). Is a sense of something ominous impending intended in your sound?

CK: There is something uncompromising which sinks into our songs, and I think it happens in a similar way to this natural order and chaos I mentioned before. There is a sense of almost inevitable threat in creating something beautiful, just as with falling in love or swimming in the ocean, but the object is not to live in fear, but to harness it and transcend it. We never try to insert anything sinister into our music because if you’re really taking risks, avoiding cheap-tricks, then some kind of purer human darkness creeps in very naturally.

On your Bio, there are physical instructions for how ‘to understand’ your music. When hearing your sound, it is very texturised. Do you encourage the audience to have as interactive, almost tangible, an experience as possible with your music?

CK: All of us appreciate a certain physicality, a tangibility in our creations. This is why we do a lot of performances that don’t involve playing music, because we want to bring something new to people, the many-sided prism that contains Wooden Veil. The reality today for most of us is digital music, but we consider our LP to be the "real" release of our album. It is this beautiful and colorful and complicated object which you can hold, and you put it somewhere, and you see it later, and you turn it around, it feels like it has something to do with you, it has entered your life and space. And this attitude of placing importance on three-dimensionality, on real experience is something that carries over, perhaps subconsciously, into everything we do.

Our sounds and efforts being reduced to 1’s and 0’s in a thousand Ipods is all the more reason for us to put more into our performances, our artworks and installations, to work in a way that allows people to see the movements, the processes and rituals which are really integral to understanding what we are doing.

Your album artwork is a photograph of a young girl with her face-painted as (please correct me if I’m wrong) what looks like a bear. Can you explain the inspiration behind it?

CK: Hanayo is a really great photographer because she has a very non-intrusive way of capturing the world around her on film. And if you know her, her photos make even more sense because there is something ethereal and nostalgic about her vision, and this candid beauty comes across in her work. The photo is of her daughter Tenko, who is amazing in her own right, at a moment which can’t really be described. I’m not sure what animal it is supposed to be. We chose this photo together because it somehow managed to get across the exact feeling we wanted to convey with the album, all of its subtleties and ins and outs. I can’t really explain it any deeper than that since the photo speaks for itself so well.

As your music is so diverse, one of the common threads seems to be an other-worldliness created through dissonant, sometimes operatic, lullabye-style vocals, shamanic beats and often electronically-transmutating layers. Was this otherworldliness part of the hermetic, as your biography suggests, ‘microcosmic’, realm you aim to create or did it happen naturally as you recorded? Generally, is your music very studiously composed or are there any improvised moments in it?

CK: We generally write by improvising and then revising…our music can be very pain-stakingly composed at times, and we follow a fairly tight score which we all write down in our own ways to remember. Our notes are a combination of drawings, German, Japanese, English and numbered diagrams labeled with our own language. The otherworldliness isn’t as much of a choice sometimes as a necessity. We run into so many communication issues that the only place we’re all on even-ground with a mutual understanding is when we leave our bodies and egos and enter into this neutral place. It can be like speaking a foreign language, when you start thinking too hard you begin to stumble and get nervous, so it’s best to let some part of you go and bring what you can to the thing being created in a very pure, human way.

When creating your music, is there a part that you often start with or is it predominantly different each time?

CK: It is generally all about the feelings of sound for us. We each choose what instruments and equipment we bring to rehearsal and then offer up various sounds and ideas to each other, almost as small gifts. Often we agree that our initial "jams" are our best music and that as we start to structure the songs and solidify things they risk losing some of the spirit. But so much is possible with composition… with simply knowing exactly when someone else will stop or change their part, which sounds obvious, but we’ve been lucky to really get into a deeper abstract level of understanding with how our songs form.

It’s usually a long and difficult journey from the improvisations to the recorded song because we’re all very critical. It takes a lot of time and patience in unexpected ways. We have a huge archive of practice recordings which we would love to edit and produce into an album or two one day, because they really capture us at our best, our essence.

Was Wooden Veil something that you had planned in some way for a long time or do you feel that it was freshly created when you all met? All five of you have been involved with projects aside from Wooden Veil. Do you think that some of your influences from those can be heard in the music of Wooden Veil?

CK: Wooden Veil is something which could only happen with this combination of people. And I don’t think that any of us could’ve foreseen this combination since it’s quite an unlikely one and we’ve all gotten to know each other mostly through Wooden Veil. We all balance each other in different ways, some of which we only realize years later.

Still, all of us bring something of our past with us, and also a lot of what we’re going through presently. Marcel has a large part in the aesthetics of our sound, especially giving it some texture and secret life. His range of solo music from tape work to drones to music concrete and sound installations has been a great asset to the group and there is a lot we have all learned from him. Hanayo has a lot more experience than anyone with music and collaborations. Much of her past work is very different than Wooden Veil, including dance club hits and a solo album on Digital Hardcore, but her voice is unmistakable and her influence and input has really shaped our sound into something unique and unrepeatable. She’s also the most experienced performer, so we’ve learned a lot from her when it comes to performing without playing music. Dominik, Jan and I have all been playing in fairly unknown endeavors for years, some which are in a similar mode to Wooden Veil, and others which run the gamut of styles from soul music to electronic.

All of us are artists or writers as well, so our other projects and practices tend to influence Wooden Veil in unexpected ways. I think that at heart we are more of an art group that also makes music than a band because our process is more like how you create an exhibition than how you write a song. It’s always very visual and poetic and thoughtful.

Berlin has a rich history of pioneering variety in music; it has given birth to the live origins of Krautrock with the Zodiak Free Arts Lab in the 60s where Tangerine Dream often performed, Einsturzende Neubaten are from Berlin, Eno and Bowie collaborated there and Liars, another iconoclastic band, were in the city to record their third album. Did this lineage make you feel more attracted to the German capital?

CK: All of us have ended up here in different ways. Marcel, for example, grew up in East Berlin and Hanayo moved here in the 90s. I think that it’s not so much a matter of what comes out of Berlin as it is what Berlin makes people do. I moved to Berlin without ever having visited, and perhaps knowing about its music and art history could have affected that choice. But I think that Berlin has something intangible which makes some people love it or hate it, a certain feeling to it that is unlike anywhere else which draws or repels. This of course is due to its insane history, all of the different strange Berlins of the past layered together. And here certain things make a lot of sense which might not fit anywhere else in the world. There’s a pervasive attitude and feeling here which allows for a certain magic that, for example, New York or London couldn’t nurse.

Do you feel that your recording environment affected your sound in any ways?

CK: We recorded a lot of the record ourselves in Hanayo’s old flat above Basso where we used to practice onto my 8-track and a stereo recorder Marcel had. Sometimes Tenko would be sleeping in the next room or doing her homework. The weather in Berlin is a very real effect. The winter sky presses you right into the ground, but the springtime is more alive than anywhere.

Two of the songs on the album were recorded live with a single stereo mic. One was at our very first show in an old Ballhouse before we even had a name and one in a big installation we did in a huge old church while we were wearing our first set of costumes. We were lucky to have our friend Simon Engerer help out with a bunch of recording and mixing, then we went to work with Rashad Becker at his Clunk studio. We recorded the second half of the album there and he mixed and mastered everything else we’d done. He’s an amazing guy, very kind and smart, with a lot of ideas in the world of sound. The studio was very low-pressure, though hours and days of us listening and playing were exhausting. I think that when we record again we’d like to go out of the city somewhere in East Germany and live in a house for a few weeks… it’s difficult to get everyone together unless we plan something like this.

In your video ‘Live in Berlin, 15/05/2007’ Hanayo is using what looks like a mangle to blow and/or hit a cymbal. Within the variety of instruments – glockenspiel, violin, banjo, bells, keys and more -that you use, do you use any perhaps more esoteric instruments that you can tell us about?

CK: Dominik has a hammer dulcimer that he brought back with him from Turkey which is played at many shows and on the album in "Birdshaped". He was taught how to play it in Istanbul by a man with no face. I’ve been collecting orphaned wooden instruments for a while here, smashed up mandolins and zithers and bella-laikas with their own stories and impossible tunings. I play just a normal handsaw and jew’s harp quite often as well.

Hanayo always assembles a percussion kit with things she finds. Her favorite is this huge dog food container which she’s played at every show we’ve had. She once tried to rig up this plastic gas container to a kick pedal, but it smelled so strongly of petrol that no one would let her use it in the practice space. The mangle you mention is actually a bell wheel I found in the woods.

Marcel has a big collection of all kinds of things used to make sound… old toys and tops and basically anything he likes the sound of. He also has a library of field recordings he’s made. One of our performances was made using only the sounds of a burning building he came across late one night alone on the street.

I’ve seen live footage of you using projections as a background to your music. You also describe your sound as ‘visual’ on your myspace page. Is the creation of a filmic, enveloping experience important to you when you play live?

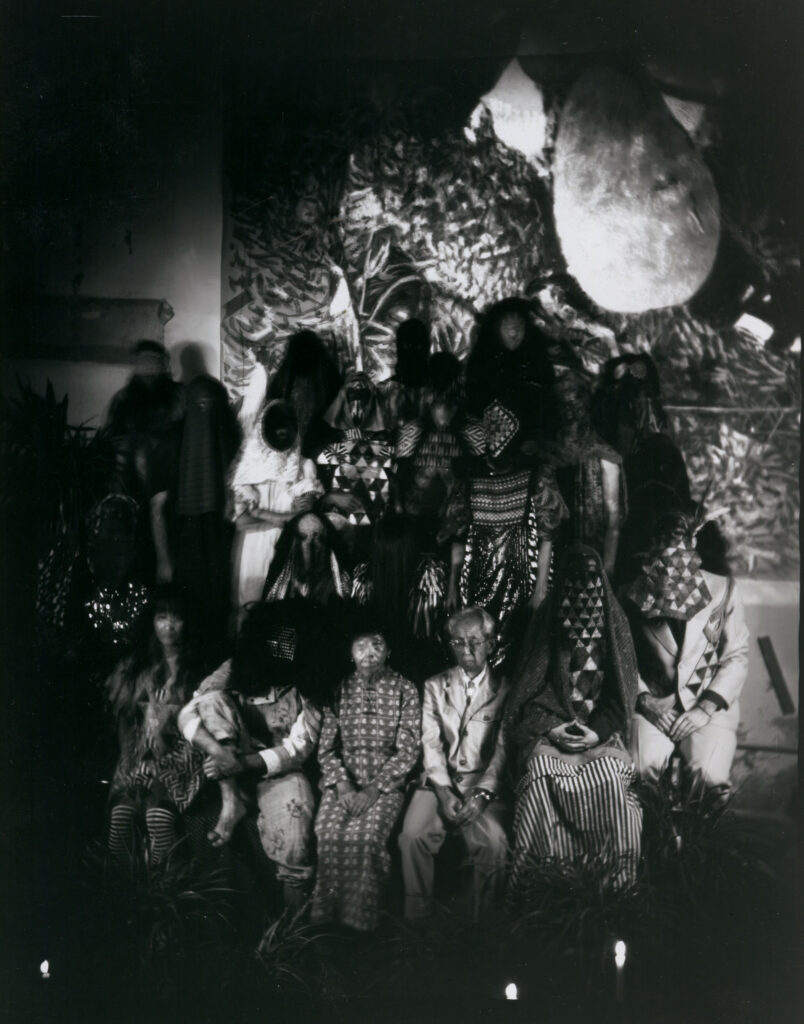

CK: Our record unveiling ceremony this past November was probably as enveloping as we can get. It took place in an old 1960s space-age brewery in Neukölln with these six huge copper vats running up to the ceiling. We had 15 of us in ritual dress, all around the room doing various actions and sounds, like 10 rituals all happening at once, overlapping, attention shifting from one corner to another. Rashad turned the vats into huge speakers and had them resonating at their natural frequencies by feeding their own sound back into themselves with contact mics and coils. Our friend Kakawaka did a portion of the ceremony where he inflated a huge balloon on the sanctuary until it was about two meters wide and exploded, echoing through the cathedral-like hall. The whole ceremony took about an hour and a half, and even while I was there performing at times I’d walk around and see these actions going on, materials being moved around, and just think, "My god, this is insane. What’s happening? What have we created?" It’s something that is impossible to document. You can see photos of a few people at a time, or of an action, but to have the feeling of this extended performance and offering, walking around to find all of the secrets, materials, meanings, you just had to be there.

We’d also like to do more exhibitions and installations in the future where we aren’t present at all, just our works and evidence, or perhaps come in once a day and do a simple action.

Your videos, for example ‘Gravity Problems’ and ‘Moon and Hamburg’ that accompany your music are often very conceptual. Do you feel that they are they just as important as the music?

CK: Certainly. And as we grow and have more resources we’d like to make longer and better films as well as books or other types of projects which all work to inform each other. We’ve really enjoyed working with the video artists we’ve already collaborated with.

Are you going to be coming to the UK anytime soon, to play live?

CK: We’ve all been traveling this winter, living in The Canary Islands, New York and Tokyo, among others, but come spring we hope to start touring and playing more international shows. If anyone wants to invite us, please get in touch!