This article was originally published on 6th January 2010, republished 6th May 2020 to mark the passing of Florian Schneider

There are many terms that always crop up during discussion of the bewildering variety of leftfield rock and electronic music that came out of Germany in the late 60s and 70s. The most commonly occurring nomenclature is the only partially useful and slightly disagreeable umbrella name of Krautrock. Probably the second most popular term is the much more useful motorik. The word, which literally means ‘motor skill’ in German, was originally coined by journalists to describe the minimal yet propulsive four four beat that underpins just a small amount of the music from this time and place. However, if this non-existent genre has anything approaching a definable quality, then this beat is it. It was a hallmark of Klaus Dinger’s drumming for Neu!, although he rejected the term, preferring to call the rhythm the ‘Apache beat’. This metronome was first used in this context by Kraftwerk on tracks such as ‘Ruckzuck’, and Can on the blistering ‘Mother Sky’.

This beat was the war drum of modernity, pushing the listener forwards into the future. It is often associated with the great transport networks of Germany, the railway lines and the autobahns. In fact the rhythm even mimics that of a car speeding along the open road or a train clattering along the rails: fast, measured, travel never ending. It was the rock beat stripped back to a glittering chassis. It was the minimalist framework on which improvisation could take place.

Of course, say this to Neu!’s guitarist Michael Rother and he laughs before stating that the rhythm was inspired by something altogether less mechanistic and more fluid: a game of football.

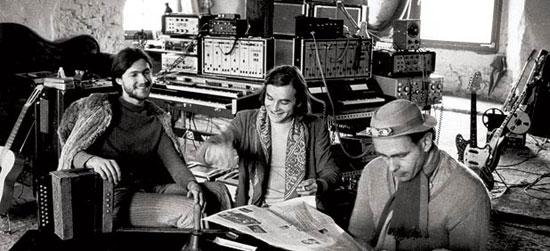

Given that he was an early member of Kraftwerk as well as Neu! and Harmonia, he is in the ideal position to judge. He was recruited between the release of Kraftwerk’s first and second eponymous album. ("Ralf Hutter was the first musician I had met who was on the same harmonic and melodic wavelength as me. We really understood each other without talking.") It was then that he met drummer and future musical partner Klaus Dinger. It was during this intense period of creativity that the motorik beat was created – the thumping rhythm that would power the new German sound out of art galleries, universities and communes into the charts and the global consciousness. There was a hint of it in the aforementioned ‘Rucksuck’, which featured on Kraftwerk’s 1970 debut album. The song is barely recognisable as being by today’s synth titans with its heavily phased flute solo and fuzzy freak-out guitars. But the metronomic beat is unmistakably taking form. The first clear cut example of this rhythm however is on ‘Hallo Gallo’, the opening track of Neu!’s debut album. (Kraftwerk would later complete the circle by adapting the rhythm back for the closing section of their break-through song ‘Autobahn’.)

But when I talked to Rother he insisted that football was the main inspiration: "I’m not sure that we thought it had anything to do with transport. I remember that Klaus and I never really talked a lot about theories we just both really enjoyed playing soccer. You know football, running up and down and everything. We even had a very good team with me and Klaus and Florian [Schneider, Kraftwerk] – he could run very fast. I remember on one tour there were some British bands there at a festival and we met them on the field. I remember we played against Family [UK hippy blues rock band] at one festival. We all loved to run fast and this feeling about running fast and fast movement, forward movement, rushing forwards that was something that we all had in common and the joy of fast movement is what or part of what we were trying to express in Neu!"

At the time football and music would have been prominent in the minds of a lot of young men in Germany. As the first generation who had grown up after WWII amongst the rubble of once great cities destroyed, and in the grey concrete neubauten (or new buildings) rebelling against parents who had often been involved in the Nazi war effort, solace was often sought in these two forms of entertainment. Football was one of the few arenas where young people could display any kind of national pride without the burden of guilt. Franz Beckenbauer had just become head of the national squad and he would take the country on to become European champions (1972) and then World Cup winners (1974).

With music, though, things were not so clear cut. In the 1950s and 1960s American and UK rock & roll dominated the landscape. US troops were stationed in many German cities, and they had English speaking stations to play the G.I.s chart hits from back home. Radios blared out either this or the inoffensive home grown pap known as Schlager (or "hit" music). It was perhaps unsurprising that all of this was creating conditions to fuel a peculiarly German avant garde revolution in sound.

Recalling the heady time Rother says: "The first Kraftwerk album was released in 1970 and when I joined them this album was starting to become quite a big success. People were crazy about ‘Ruckzuck’. I remember Conny Plank saying that on the heavy drug scene in Munich they listened to Kraftwerk all the time. Everyone was on drugs apart from us guys!"

This said, the young musician felt that Kraftwerk lacked the necessary drive and direction and he left soon afterwards, taking Dinger with him to form Neu!: "When the atmosphere wasn’t right, the sound wasn’t right. I think it was quite terrible and apart from those good times on stage there were a lot of arguments, especially between Florian and Klaus. They were arguing a lot. So we tried to do the sessions for the second Kraftwerk album in summer of ’72 and that failed because it was quite clear that we were dependent on some rough live atmosphere to make us create that enormous noise and heavy beat that we did. So it was just natural for us to separate. Klaus and I, we had the idea that our aims were closer so we should carry on together. So we got in touch with Conny again and so in December we recorded the first Neu! album."

The name Neu! was suggested by Klaus whose girlfriend was working in advertising. It fitted neatly with their relatively stark modernist sound and broke from all of the rock traditions of the past. But after the release of their fantastic debut, which sold 35,000 copies on release, and a poorly received follow up, things started to disintegrate. (The pair ran out of money recording ‘Neu 2’ and the B-side is made up of tracks from the A-side recorded at different speeds. The techniques used to make the second side can retrospectively be claimed as far-sighted but at the time people felt a joke was being played on them.) The arguments that had spoiled their time in Kraftwerk were now beginning to affect Neu! Whatever fueled the animosity between Klaus and Michael (it was arguably drugs as Michael is fairly clean living and Klaus has gone on record saying that he is proud of his consumption of over a thousand LSD tabs) it caused him to seek a hiatus and while visiting "Kosmische" electronica band Cluster (his friends Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius) at their studio in Forst, Rother had such a good time he ended up moving in with them. It was during this period that the trio conceived of the group Harmonia. This would all but signal the end of Neu!

It is often said that there was little musically to link Can to Guru Guru to Amon Duul II to Frumpy to Kraftwerk to Popol Vuh and so on, but Roedelius makes the point that there were important ties that bound them: "There was a similar spirit. We were all children of the time. We were all part of the so-called flower power generation. We all worked in the same mood. Most of us worked in communities. Most of us tried to live a healthy life. It split afterwards; when the others like Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk got really famous. Then it became something else but in the beginning at point zero, there was the same spirit." He laughs when he recalls playing as part of Kraftwerk at a festival and concludes: "We were all jamming together on stage. We had all of our equipment set up together. It was fun and it sounded very loud but I don’t think it was so nice for the audience!"

Recalling the period, Rother says he "fell in love" with the music of Harmonia and that he considered it then to be his main project. He recalls his Farfisa beat box saying: "They were designed to be like metronomes for practise or for people playing dance music, like when elderly people get together for a tea dance. You know, um cha-cha um cha! Um cha-cha um cha! That was fun doing the equalising and doing the filtering and adding delay and putting it through a wah wah peddle and other machines to chop up those rhythms to make them sound more interesting… Mine was very simple, it had pre-programmed beats but you could put several of those on top of each other and do several variations but you have to use good manipulations to make them sound good."

The process of turning possession of the motorik beat over to the machine had begun in earnest.

Of course there were other groups around in Germany using electronics (Cluster and Tangerine Dream to name but two) but Kraftwerk had an edge in that they could see the bigger picture with greater clarity. They eventually built their own studio Kling Klang, they owned the records and tapes that they made and licensed them to EMI, ensuring that they kept complete control of the design and artwork. In this respect they were a very DIY, ‘punk’ outfit. It is perhaps unsurprising that they hailed from Dusseldorf the design and fashion capital of Germany, given their masterful control of their own image.

At the dawn of the 70s Ralf Hutter (an organist) and Florian Schneider (a flautist) met through a jazz improv course, quickly forming then disbanding the jam collective called Organisation before creating Kraftwerk. What they committed to record at the time feels austere and unfocused, but this perhaps can be put down to how much fun the group appeared to be having when playing live. At one gig in 1971 the pair, so it seems, were hosting what we would nearly 20 years later have considered a rave. Speaking to The Face magazine in 1987, Hutter recalled: "I had this little drum machine. At a certain moment we had it going with some loops and some feedback and we just left the stage and joined the dancers." The pair would stay in the crowd dancing to the proto-house beat until the primitive equipment stopped working or burst into flames.

In 1973 they recruited Wolfgang Flur, who had originally played in Rother’s teenage rock band, Spirits of Sounds. He was so disgusted with the childishly small drum kit the band expected him to practice on that he ended up building his own set of electronic drums, becoming in the process probably the world’s first electronic drummer.

Recalling the genesis of the track that the new album would be built around, Schneider said: "We were on tour and it happened that we just came off the autobahn after a long ride and when we came in to play we had this speed in our music. Our hearts were still beating so fast so the whole rhythm became very fast."

The group took to physically driving up and down motorways recording noises as they went and then trying to recreate them on synthesizers and locking the grooves in place with their first ever sequencer. The eventual 22 minute long, eponymous track was the first definitive statement that Kraftwerk had made and (in a mainstream sense at least) it marked the birth of synth pop and techno as we know them today. It was a staging point because it combined the new electronic rhythm of the motorway as well as, in the closing minutes, the motorik beat.

The motorik sound represented a metaphorical journey speeding away from the recent past – a high velocity transit away from the recent horrors of Nazism and World War II. The autobahn was inextricably linked with the dominance of the Nazis in the 1930s and early 1940s. The new roads provided links between all of the major cities in a manner that only previously been dreamed of. Hitler promised that he would eradicate unemployment and through the building plan he nearly achieved this goal. The middle classes had better transport links and the mercantile classes had an abundance of new markets that they were able to reach. And for Hitler himself he had achieved what he had always wanted: "Totale Mobilmachung" or total mobilisation for the troops of the Third Reich. By 1939 he was responsible for 3,000 km of new road. As soon as the war was over he planned that the people would be able to drive wherever they wanted in the Volkswagens he had promised to every family. It took a band as forward-looking as Kraftwerk to rescue the liberating nature of the autobahn back from the fascists. As soon as you hear the child like refrain "Wir fahr’n, fahr’n, fahr’n auf der autobahn" ("We are driving, driving, driving on the autobahn.") you realise that Kraftwerk have won an important victory. The song is as much a riposte to the previous generation as it is a nod of respect to The Beach Boys and American road music. (It may or may not be coincidence that the rhythm to this refrain is that of ‘Barbara Ann’.)

When discussing this theme at the time Hutter said: "We were born after the war . . . it is not much of an incentive to respect our fathers." Speaking about The Beach Boys he said: "In their songs they managed to concentrate a maximum of fundamental ideas. In a hundred years from now when people want to know what California was like in the 60s, they only have to listen to a single by the Beach Boys."

After the release of the album Kraftwerk enlisted Karl Bartos so they could tour the States and the classic line up of the group was complete. On this wildly successful visit the group talked to legendary hack Lester Bangs. Hutter explained to him: "After the war German entertainment was destroyed and German people were robbed of their culture putting an American head on it. I think we are the first generation born after the war to shake this off." Bangs’ piece at once reflects his undeniable genius and his tendency towards childish idiocy but ignore some of the daft blow job jokes and snide Nazi jibes at the band’s expense and you have a prescient feature, showing how the further he got away from mainstream American rock, the more devastating his

critique became. By saying that "the Germans and the machines" were the future of rock and suggesting that they were responsible for his favourite rock music as they’d developed amphetamines during the war, he was toying with what would become one of transgressive rock’s favourite pastimes of the next few decades: exploring the link between totalitarianism and music. And out of all of the acts who would visit the fascist dressing up box, it was David Bowie who would get his fingers burned the most. But just before this happened, he (along with Iggy Pop) would get name-checked on the title track to Kraftwerk’s very next album Trans Europe Express . . .

Speaking to the Quietus last year about this 1975 tour of the States and how they became an unlikely cult concern amongst black fans of funk and proto disco, Bartos said: "This happened not too long after my first encounter with Ralf and Florian. In 1975 we went over the Atlantic and spent 10 weeks on the road. We went from coast to coast and then to Canada. And all the black cities like Detroit or Chicago, they embraced us. It was good fun. In a way apparently they saw some sort of very strange comic figures in us I guess but also they didn’t miss the beats. I was growing up with the funky beats of James Brown and I brought them in more and more. Not during Autobahn or Radioactivity but more and more during the late 70s. We took some black beats into our music and this was very attractive to the black musicians and the black audiences in the States. In a way probably it reminds me of what The Beatles did. They took some Chuck Berry tunes and they transferred it to our European culture before taking it back to America and everyone understood that. In a way that was probably what we did with black rhythm and blues. But we mixed it of course with our own identity of the electronic music approach and European melodies. And this was good enough to succeed in America."

He said it was some time before he actually realised that they’d had a direct effect on black dance music producers: "Well it happened [some years later] actually when we were in New York and we were in the street and we saw a record shop full of our records and black people stood in front of them making jokes about the covers and about how strange we were looking, but people were making loops out of ‘Metal On Metal’ and dancing to it. These loops were going on forever! Made from just these heavy metal sounds! They were break-dancing to it. Then we were aware that we had access to this culture."

The phenomenal success of ‘Autobahn’ both signalled the rise of Kraftwerk to international prominence and the end of the genre’s imperial phase elsewhere. But on the world stage the long and fruitful history of electronic dance music was only just beginning.

MOTOR SKILL