Nobody understands reinvention better than Josephine Foster. After a youth spent working as a funeral and wedding singer as well as a short-lived attempt to make it in the world of opera, she started to record and release her own material. Each new Foster album marks a radical departure from the last one, whether it’s the gentle folk of her 2001 debut There Are Eyes Above, the psychedelic rock of 2004’s All The Leaves Are Gone which she recorded with her backing band The Supposed, or the bizarre A Wolf In Sheep’s Clothing from 2006, which features unorthodox re workings of songs by German composers such Franz Schubert and Johannes Brahms.

Now, Josephine has released possibly her most ambitious record yet. Graphic As A Star takes 26 poems from the 19th century American artist Emily Dickinson and sets them to a backdrop of sparse, twinkling orchestration. The meshing of the sparse backdrop and Dickinson’s words is both haunting and soothing: a desolate landscape populated by images of love, loss and isolation.

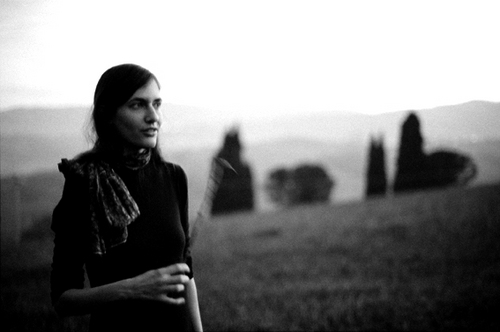

The Quietus caught up with Josephine to discuss the art of reinterpretation, people’s fears of poetry, and the importance of solitude.

How did the idea for the project come about?

Josephine Foster: The idea came last winter reading her poems, and later reciting some which brought some melodies out. The recording is material drawn from those initial readings.

It’s a big departure from your previous album This Coming Gladness, and especially some of the more psychedelic folk/rock work you’ve done with the Supposed. How hard was it to make such a big leap in style?

JF: Singing alone eliminates the filters between you and the song. I love arranging songs with other musicians as well, there is no disadvantage either way.

One of your previous albums, A Wolf In Sheep’s Clothing, took inspiration from the compositions of Brahms, Schubert etc, so looking to the past for inspiration isn’t something new for you. What appeals to you about working in this way?

JF: To me there is no difference in being attracted to singing an old song or a new song its more about a good song or work of art really feeling attractive. There is something liberating about using older material however in that the rules are loosened up considerably.

How much familiarity with the work of Emily Dickinson did you have before you started the project?

JF: It didn´t have a deep effect on me when I read a few poems of hers in school, although I didn´t dislike them. It just wasn´t the moment and more recently things turned out to be much different.

Did you feel kind of affinity to her as a person or artist? A lot of her work deals with loneliness, isolation, death…

JF: At the time of writing the melodies I happened to be living a pretty secluded existence, but beyond that I don´t identify with her personality or have that kind of affinity. What I identify with and deeply admire is her reverence for nature, her understanding of love, and most of all perhaps how she steps into and explores points of view of other beings far outside herself. Of those themes you mention, after reading her poems I´d say that death is certainly a big theme but those others you mention seem minor. Her work so outsizes the imagination that I don´t even think about her physical form, especially as this typical image of a small brooding woman.

Do you feel a sense of nervousness in setting her words to music, because she’s such a celebrated figure?

JF: No, because I don´t intend to make a final statement on her poems. They are of a caliber that if hundreds of people read or sang them there would arise infinite possibilities. I can only hope that my melodies hold their own with the poem and reveal some authentic perspective or possibility hidden in the poem-not overstepping her words yet not being so self-effacing as to have no identity. In a way song settings are a coloring of the skeletal black and white text, voice and melody and rhythm flow through the prism of the poem and give it the flesh and blood of music.

Musically, the album’s very stripped back. It’s bare and sparse. Was that a deliberate attempt to give the words room to breathe?

JF: It was as simple as working with the means and environment I was living. Also I was drawn to these particular poems perhaps for their lightness and colloquial language, their brevity and immediacy. The magic thing to me is that by setting a poem to a simple melody it facilitates the memorization of the poem. Once the melody was there, the poem became a more tangible object to meditate on.

Your remote setting while writing the album obviously had an influence in you choosing her work. Is the creative process always a lonely one?

JF: Solitude is useful for many types of work. Its not lonely at all however, its the opposite. Its a communion with the deepest parts and in effect you are cultivating something to be shared-which connects you to the world. A rural setting to me is ideal because there is an element of rapture while singing or writing that only occurs outdoors.

For a lot of people, the concept of poetry is immediately alienating, even though a lot of poems – whether it’s Blake or TS Eliot – are given so much more depth when read aloud. Why do you think that is?

JF: I think its reading aloud our favorite poems, even singing them, learning them by heart and sharing them with others that give life to poetry. Just passively reading poems seems incomplete, like reading a score of music without playing it. It’s a sad state of affairs that many people’s experience of poetry is dissecting poems from books on an intellectual level. To me a poem best be heard to be felt and spoken to be experienced.

Stemming from the idea of poetry being alienating, is one of the reason’s you chose Dickinson her simplicity?

JF: Her poetry is so full of rich mysterious layers of meaning, while remaining generally short and to the point-its the work of a master.

When you were younger, you worked as a funeral and wedding singer. What was that like?

JF: It happened almost by accident, and I ended up singing in this long cabin wedding in the Rocky Mountains. I loved being a witness and a part of these strange rites of passage and being privy to the various religious subcultures surrounding them. Without an awareness of death I’m not sure that a romantic state could be possible – love of life is the feeling of its shortness precious value. Its not clear to me why that would be unnatural or morbid whatsoever.

You also used to want to be an opera singer. What kind of influence did it have on your work?

JF: Whether or not I mastered the art of operatic singing (I didn’t) as a musician I´m very grateful to have explored techniques which now form a part of how I express myself in sound. In classical music there are many song forms and music which I absolutely love, and there is something riveting in operatic singing to me -perhaps just the very strong direct vibrations which I believe very positively effects both the singer and listener.

Josephine appears at Cafe Oto tonight to play solo material from her 2008 solo album ‘This Coming Gladness’. The show starts at 8pm, and tickets are either £10 in advance or £12 on the door.