The basic facts of Arthur Russell’s biography will be familiar to anyone who has heard his music, and they go like this: He was born in Oskaloosa, Iowa, in 1951. From there he spent some time in San Francisco in the late 60s, absorbing Buddhist philosophy and developing his skills on the cello. He then moved to New York where he remained, consistently producing a wide range of music until his death from AIDS related illness in 1992.

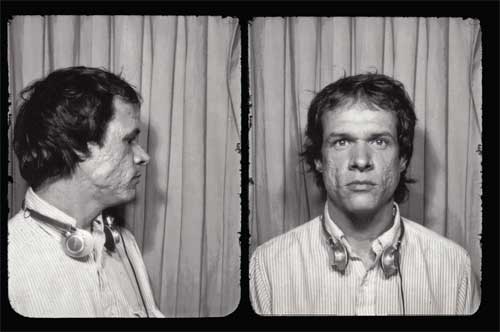

This much we know. But aside from his recorded music, he exists only in the hearts of those who knew him and the minds of those who have discovered him through his music. The 2008 documentary Wild Combination filled in many details of his life, told mainly through interviews with his family and loved ones, yet the man himself remained elusive. So the idea of a written biography of Arthur Russell is a daunting prospect – after all, the man can no longer speak for himself. Tim Lawrence handles the task masterfully, however, marshalling his extensive research, presenting accounts of events even where two seem inconsistent, and always avoiding the temptation to draw trite conclusions. The result is a fascinating book and an image of a deeply troubled, uniquely gifted artist.

We know now that Arthur Russell was one of the most exciting musical voices of the last century. His gifts were extraordinary. His work spanned mutant disco, minimalist composition, introverted pieces for voice and cello all bathed in echo, and propulsive yet delicate pop music. And despite being widely ignored until a series of posthumous reissues in 2004, Russell was dedicated to melody and rhythm in a way that is often sneered at in the world of sophisticated modern music. He was also a sensitive lyricist, who could draw whole worlds of emotion out of the smallest moments, a gifted and a disco producer with a unique sense of rhythm and groove.

All of the above could be said to describe the man adequately, but does it really capture the essence of the fellah? Not really. We need categories to make sense of the world, especially when describing something as ephemeral as music, but Arthur Russell’s music always seemed to exist somewhere else, beyond anything familiar, safe or easy. It comes to us today completely out of context. Through meticulous attention to detail and chronology, Tim Lawrence’s book manages to piece together memories, letters, and records to give a very real sense of who Arthur Russell was; while placing him firmly in the times and places he lived. From his work with Allen Ginsberg, to his influential role as director of the Kitchen art space in New York at the height of the Downtown movement, to his passion and natural gifts for dance music just as gay liberation spread through the city’s discos, Russell lived and worked through an incredibly productive time in New York’s musical history. While Colombia Records’ John Hammond wanted to make him the next Bruce Springsteen and Philip Glass tried several times to help him gain a foothold as a serious composer, Arthur seems to have been constantly torn between his desire for commercial success and his fidelity to music as a force for liberation, collaboration, and exploration.

As such, there are no easy answers here. The book reveals numerous opportunities that were presented to Russell; chances to seize the sort of success he craved. Whether he failed due to insecurity, self-sabotage, dedication to experimentation, chronic inability to finish work, or the naïve idea that the world was ready for him, is never clear. The book accepts the contradictions. It sometimes feels like peering through frosted glass, or listening to an old friend on tape. On other questions the book compensates for the ambiguities of Russell himself. Lawrence’s approach combines an academic’s attention to cultural context with a record collector’s passion for the details of the recording process. Parts of the text are likely to appeal only to serious fans of Russell’s work. Nonetheless, it is also a fascinating insight into the vibrant constellations of collaboration, politics and experimentation that were taking place, even as Russell seemed to confound them. It is also a tender book. As it draws towards its end, the sheer weight of the tragedy of Arthur’s death is difficult to bear.

That Arthur Russell should have finally found recognition in the decade now ending makes a lot of sense. The internet has to some extent rendered the old categories of music and commercial modes of distribution quite meaningless. Artists are now free to cross boundaries without sacrificing recognition. Russell’s music embraced technology while remaining deeply concerned with simple human emotion – It continues to speak to us; it remains relevant. Lawrence does not eulogise or wax romantic about Russell’s belated acceptance. This book is a vital document of the man and the times he lived in. It is nothing less than justice being done.

Excerpt from Tim Lawrence’s Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-1992

World of Echo

The Lama Ngawang Kalzang had been meditating for twelve years in various caves and retreats in the wilderness of the mountains of Southern Tibet. Nobody knew him, nobody had heard of him. He was one of the many thousands of unknown monks who had received his higher education in one of the great monastic universities in the vicinity of Lhasa, and though he had acquired the title of Géshé (i.e. Doctor of Divinity), he had come to the conclusion that realisation can only be found in the stillness and solitude of nature, as far away from the noisy crowds of market-places as from the monkish routine of big monasteries and the intellectual atmosphere of famous colleges. The world had forgotten him, and he had forgotten the world. This was not the outcome of indifference on his part but, on the contrary, because he had ceased to make a distinction between himself and the world. What actually he had forgotten was not the world but his own self, because the ‘world’ is something that exists only in contrast to one’s ego.

Lama Anagarika Govinda, The Way of the White Clouds

Having filmed Sun Ra in the late 1960s, Phill Niblock decided he didn’t want to repeat the exercise with anyone else, but Arthur’s not-quite-ofthis- world persona gave Niblock second thoughts, and he ended up filming Arthur performing a selection of his voice-cello World of Echo songs at the Experimental Intermedia Foundation on two separate occasions in the autumn of 1985—both times without an audience. “Arthur had this strange lighting setup with a bunch of cheap lamps and filters and a dimmer board that Steven Hall was manipulating,” Niblock recalls. “The lighting changed dramatically from moment to moment, so it was all quite interesting.” Shot on a single camera and without breaks, the first video was marred by interference while the second ran smoothly. As far as Niblock knew, Arthur was planning to release the second performance, provisionally titled “Terrace of Unintelligibility,” in a video-only format, but the filmmaker had come to appreciate there was little point asking Arthur what he was going to do with the tapes.

Arthur continued to perform songs from his solo, voice-cello World of Echo project during 1985, more often than not at the Experimental Intermedia Foundation, where cheap wine could normally be found in a corner. “Phill’s loft was a much more relaxed hangout than the Kitchen,” notes Arnold Dreyblatt. “Phill may have been less critically curatorial than some of the directors of the Kitchen, and it’s true that he did not present some of the more provocative acts that appeared at the Kitchen, but it is not an accident that Arthur became friends with Phill and ended up performing at this very off-the-mainstream space.” Arthur also liked the audio tracks of Niblock’s videos so much he resolved to release a World of Echo album. “We would start at eight or nine in the evening and go on at least until 3:00 a.m.,” recalls Eric Liljestrand, who confirms the songs were recorded almost always at night. “Arthur always tried to maximize the time, so we did everything in a rush. It’s not like Arthur did endless takes of the same thing, but the tape was continually running and the sessions were pretty blurry to me.”

Because he was the only instrumentalist in the sessions, Arthur realized he could break with the standard practice of playing in a quiet, isolated room, and so he set himself up in the control booth in order to hear exactly what the engineer was hearing and tweak the sound according to his own taste as he played directly into the mixing board. Then, when he was done with singing or playing, he would cut, re-equalize, and manipulate the recordings, weaving them together as if he were a time-traveling tapestry artist. During these sessions it became standard for Arthur to splice together separate tapes, and he would regularly grab a track from one tape and fly it into the multitrack of another while his onlooking engineer tried to stay calm. “We would be mixing on a piece of tape, and I would see a splice go by,” recalls Liljestrand. “It was all very confusing. I could never really tell what we were working on until it was done.” The ghostly accidents that arose from Arthur’s insistence that they re-record over old tape became an integral part of the sonic fabric. “There would be leakage of an old track into a new track, which drove me bonkers,” explains the engineer. “But it didn’t seem to bother Arthur.” Arthur was more concerned with Liljestrand’s habit of double-checking every time Arthur instructed him to record over an old multitrack, and on one occasion he “got really mad,” re members the engineer. But as their working relationship deepened, Arthur relaxed and took to standing over Liljestrand’s shoulder, clenching his fists and rocking backwards and forwards in a virtually imperceptible motion as the material was played back to him. “It was almost like he was dancing inside, and only a little bit was coming out.”

Working into the early hours, Arthur and Liljestrand studied a series of recordings that showcased the startling complexity of Arthur’s amplified cello—an instrument that, in terms of Arthur’s releases, had been restricted to playing orchestral scores and making cameo appearances on twelve-inch singles. Arthur had started to amplify the instrument in San Francisco, but it was only when he combined an MXR Graphic Equalizer with the Mutron Biphase box (a hundred-dollar piece of equipment that generated resonance by combining the technology of phase modulation with the wahwah pedal) that the electric cello sounded (as he put it) “really beautiful.” “The result is that a very new road is opened to me with the cello bringing it a long way from its traditional orchestral role,” Arthur wrote to Chuck and Emily in 1977. “I don’t think anyone plays this instrument this way, amplified with such a clear sound.” Arthur went on to acquire a bewildering number of other effects boxes, which he would combine as he searched for a “deep and shifting feeling” that resembled an “undertow current” (in the words of Hall). “He took his cues from heavy-metal guitars, and was looking for the same depth of sound and impact,” notes Hall. “He was fascinated by their huge, monolithic soundprints and studied various metal guitarists in his quest.”

Arthur’s playing was directed toward sonic range rather than virtuosic skill. When his fingers flew up and down his cello’s neck in darting, athletic movements the instrument twanged like a funk bass, yet when he bounced his bow on its strings or tapped out rhythms on its wooden body, the sound was percussive. On some songs Arthur’s cello reverberated with electrostatic intensity as the bow screeched over the instrument’s strings, while on others it rumbled deep and threatening, or generated a modulated bleeplike signal, or even shifted between a series of affects. “Echoing the chance operations of John Cage and Jackson Mac Low, he loved constant, random modulation,” adds Hall. Indeed the cello only sounded like a cello when Arthur played pizzicato, sending off gentle, acoustic sounds of such subtle detail that even the movement of the air around the strings seemed to be audible. And although feedback was an ongoing curse that could result in chaos, by the time of the World of Echo recordings Arthur had come to

describe these untameable waves as “feedback harmonies.” Arthur’s voice discovered a similar freedom during these insomniac sessions. Having taken vocal lessons at the Ali Akbar College of Music, where he let go of the objective of clear pronunciation and started to slur his vowels, Arthur continued his studies in New York with the vocalist and composer Joan La Barbara, who taught him how to utilize the bones in his nose to get a droning, nasal sound. “Arthur was a dedicated musician with lots of ideas,” recalls La Barbara. “His time at the Kitchen was very rich and meaningful for the downtown music community.” As with all her students, La Barbara went through her basic physical warm-up exercises with Arthur, “because a good singer is like an athlete and sings with the entire body.” Then she ran through tongue exercises, because, as La Barbara notes, the back of the tongue is connected to the vocal cords, and the exercises help bring blood directly into the area and warm it up in preparation for singing. Finally La Barbara moved on to working with vocal sound. “I always do a lot with resonance and with placement of the sound in specific areas in the face and head, focusing on specific bones such as cheek bones, the fore head, and, of course, the wonderful nasal resonances where one can make extreme sounds.”

On the World of Echo recordings, Arthur’s languid voice discovered a freedom of movement that had not been available in the comparatively formal settings occupied by the Flying Hearts, Loose Joints, Dinosaur L, and the Necessaries. Suspended between the musical traditions of India, Brazil, and North America, Arthur whispered and moaned, glided between notes, and explored unexpected directions as he moved through a series of seemingly impossible maneuvers. Like a kite, he combined tension with darting movement as he switched across a range of barely fathomable time signatures, yet the energy expended on maintaining his poise and flow didn’t result in a loss of range and evocativeness. At times he sounded as though he was about to swallow his mike, while on other occasions he might as well have been singing on a ferry bound for Staten Island. And as his words blurred into each other to the point of being indistinguish- able, Arthur edged away from the obligation of verbal communication and relaxed into an economy of phantasmagorical sounds. “After listening to tapes of World of Echo as well as foreign language singing,” Arthur wrote in a later set of program notes, “I’ve enjoyed the musical effect of words as sounds, but where the meaning is not totally withdrawn.”

Evoking textures in infinite detail as they helped each other to discover their full expressive range, Arthur’s voice and cello moved with a subtle dexterity as they headed into a Delta Lab 2 delay box, which generated echo and reinforced the illusion of disappearing sound. Yet whereas most dub producers sought out murkiness, Arthur hoped to create an echo that was scintillating rather than muted. “I like the bright sound, I like compression,” Arthur wrote in a letter to the mastering engineer of the tapes. “Please make it as loud as possible.” Arthur asked friends if they thought he was using too much reverb, and Ernie Brooks, who placed a high value on hearing the words of a song, told him that he was. Persevering, Arthur created a chorus of voices that combined in a flickering, spectral harmony. A shimmering, mystical celebration of vowel sounds, “Tone Bone Kone,” which would become the opening song on the album, expressed itself as textural sensation rather than textual meaning, while other songs evolved in meandering, mesmerizing threads, fluttering about in tender butterfly movements that were impossible to predict and would have been terrible to contain or discipline. “When I have written songs, the functions of verse and chorus seem to be reversed for some unknown reason,” Arthur wrote in a set of accompanying, unpublished notes. “The idiomatic style I ended up using is not immediately reference-able.”

Arthur’s decision to blend all of the songs into one continuous track contributed to the unraveling of structure, while his acoustic reworkings of “Let’s Go Swimming,” “School Bell / Treehouse,” and “Wax the Van” illustrated the way his songs could discover an even greater degree of elasticity when they weren’t required to follow the pulse of a drum. “It’s the same song just different instrumentation,” Arthur said of “Tree House” (as it was renamed on the album) in an interview with Frank Owen published in September 1986. “I think, ultimately, you’ll be able to make dance records without using any drums at all.” Songs without beats, Arthur added, would be the source of “the most vivid rhythmic reality.”32 In his unpublished jottings, Arthur also noted that his aim was to “redefine ‘songs’ from the point of view of instrumental music, in the hope of liquefying a raw material where concert music and popular song can criss-cross.” That made World of Echo the song-oriented successor to Instrumentals (1974—Volume 2), which introduced popular forms into compositional music, and 24 −−> 24 Music, which channeled orchestral improvisations through disco.

Along with the music’s hushed, late-night atmosphere, the re-recording of older songs in an acoustic/dub format suggested that songs contain their own echoes—their own ability to discover a reincarnated form that’s both the same and different. The self-referential twist suggested an introspective mind-set, and the use of sonic space, in which Arthur’s voice and cello bounced around the three-dimensional contours of the mix, bolstered the impression that the recordings amounted to an internal, multidimensional play area that could be explored ad infinitum. At times Arthur appeared to be playing a game of existential hide-and-seek with his own shadow: his schizophrenic edits resulted in the multitrack tapes shifting between contrasting sonic environments—flat or hissy, spacious or closed, muffled or clear, dry or wet, populated or empty—in rapid succession; and because the voice-cello setup was so sparse, disappearance and loss were continually evoked as Arthur’s feathery voice floated away, or a scratchy strike on his cello reverberated into thin air, and nothingness was met by the next word or note. Sounds moved across the multitrack tape like the gentle, recurrent movement of the seashore, where a receding wave would begin to reveal the sand underneath, only for the next wave to fold over the escaping undercurrent.

Channeling the jams of the Mantric Sun Band, the drones of the Ali Akbar College, and the meditative chanting of Ginsberg through the deserted downtown space of the Battery Sound studios, World of Echo was Arthur’s latest attempt to blend West Coast spirituality with the East Coast avant-garde. Devotional and ethereal, the songs were delivered as twilight prayers as Arthur lost track of the distinction between himself and the world—perhaps like the Lama Ngawang Kalzang following twelve years of his cave- and mountain-bound meditation. John Hull notes that “Sound places one within a world,” because the auditory is experienced inside the body of the listener (in contrast to the visual, which is experienced as a separate scene to be observed). Yet in World of Echo Arthur appears to have transcended this state, as well as the mind/body divide (the notion that the physical and the nonphysical are always separate and opposed), because the recording worked as a form of abstract materialism in its illus tration of the way movement isn’t just physical but is also about potential. Stripping music down to its bare essence—to simple sequences of notes and friction and air—Arthur revealed the infinite quality of sound and existence.

As a rule, Arthur didn’t get along with label bosses. When relations with the decision-makers at Sire and West End deteriorated, he cofounded his own label, and even this move simply became the precursor to his fallingout with his partner. But things seemed to be different at Upside, where he felt comfortable with Gary Lucas and Barry Feldman. “Arthur had this great résumé, but everyone in the scene treated him like shit—like, ‘Fuck you, Arthur!’” says Feldman. “This would go on all the time, and he just seemed beaten down by all of it. I think he liked me because I wasn’t very judgmental. Respectful of Feldman’s background—the label boss grew up with jazz and could play compositions by Ornette Coleman, Charlie

Parker, and others—Arthur began to call Feldman up and wait for him to start a conversation, or drop by the Upside office to share musical obsessions and low humor. And at some point during the second half of 1986, he decided that things were going well enough for him to entrust Feldman

with World of Echo.

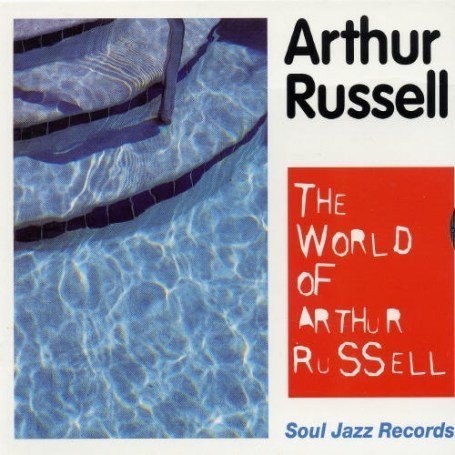

The album contained fourteen tracks, two of which were live takes recorded at the Experimental Intermedia Foundation. “He blurted out, ‘Barry, I think you really should release this record,’ and then practically ran out the door,” recalls Feldman. “The album was completely done. If he had proposed it and asked for money, I would have probably said, ‘No.’” The Upside boss reasoned that if he gave Arthur one thousand dollars he’d have one problem, whereas if he gave him three thousand dollars he’d have three problems, but Arthur wasn’t asking for money, and although Feldman wasn’t a big fan of the record, he paid Arthur a token sum and crossed his fingers he would break even. “By that point there were so many problems with cash flow the idea of making a lot of money went out of my head,” he says. “But I was like, ‘Fuck it! I’m not making any money, I might as well

put out a cool record!’”

Aside from a persnickety review in New Musical Express, the album received strong press. Billboard declared it to be “one of the finest avantgarde pop albums in some time,” while Frank Owen described the album as being “mournful, mysterious, intimate, understated, indeterminate and altogether beautiful.” Writing in Melody Maker, David Stubbs was even more adulatory. “This is what is left when the Beat has eaten itself, when the crunch of hip-hop has crunched itself to dust,” he wrote. “‘World Of Echo’ is an orbit of resonance, a giant, subterranean repository of Dub. . . . It works, as a fuzz, a blur, a ric, throbbing pulse, a signal in space. . . . I imagine that, at some point in the future, it will be possible to dance quickly and furiously to ‘World Of Echo,’ once the rust-marks of the beat-grid have made a sufficiently indelible mark on the folk-memory, enabling the listener to refer to his ancient instincts to know what to do with his feet.” Melody Maker went on to list the album at number twenty-two in its chart of the top thirty releases for 1987, but sales were disappointing. “I was getting great press, but the stores barely took it,” says Feldman. “I think I pressed up 1,200 copies and sold 900 at the most.” As the movement in the stores faded, Arthur asked Feldman if he would place a football-shaped sticker on the cover that contained a single word: Unintelligible. “It was Arthur’s way of saying to people, ‘Don’t expect to get it the first time, or the second time. Don’t listen to it that way.’ The sticker became a running joke.”

Arthur appeared to be in good humor. Although his Flying Hearts, Bright and Early, and Corn recordings remained unreleased, he now had four albums to his name in addition to the two he had recorded with the Necessaries, and that was good going for any artist, let alone a compulsive procrastinator. “The next album might be a bit more of the same, except with drums,” he told the Oskaloosa Herald in December 1986. “Or there may be a country album, because I like that a lot. Playing in a country band would have been perfect for me.” A few months later, in April 1987, he talked of the Upside LP as being a “sketch version” rather than a “complete version” of World of Echo. “I want to do the full version which will have brass bands and orchestras playing outdoors in parks with those bandstands that project echo,” he commented. “I also want to have Casio keyboards on sail boats.” Arthur was still planning, still dreaming.

Copyright Duke University Press, 2009. Reproduction without permission is striclty prohibited.

www.timlawrence.info