Dieter Meier’s black leather shoes click like a boarding school prefect’s as he makes his way purposefully down the narrow concrete corridor ahead. His grey hair curls tightly at the back of his head down to the collar of a smoking jacket that cuts a flattering line over a crisp white shirt. His charcoal trousers are perfectly tapered, his cravat tucked just so beneath his chin. He settles down on a black leather sofa in a subtly lit dressing room and mutters to a hovering record company employee that he’d like a beer. His manner confirms his refined manners but, in its firmness and its failure to offer anyone else present a drink, recognises his own elevated status in this artificial situation.

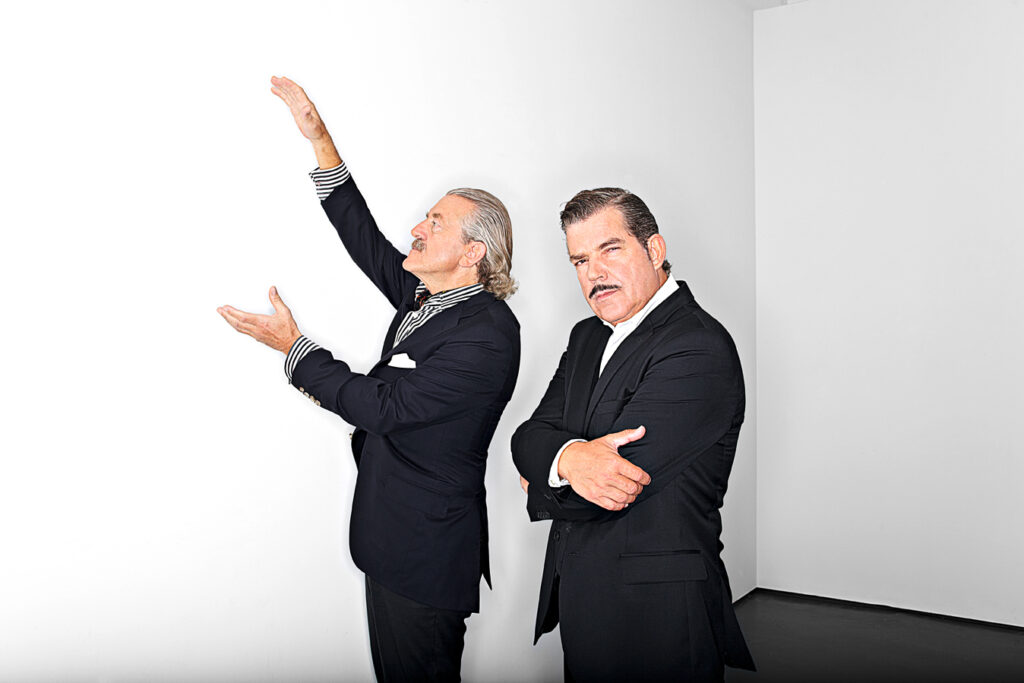

It’s clear that there are many other things Meier would rather be doing right now. It’s midnight on a cold October Berlin night, an hour after the premiere of his latest adventure, Touch Yello: The Virtual Concert, has come to an end. Created to overcome Yello’s refusal to perform live as they promote their latest album – yet to be scheduled for release in the UK, but already a number one hit in their Swiss homeland – Touch is a typically Technicolor collection that draws upon Yello’s well established sonic template, and though it veers dangerously towards mid 90’s chillout soul on a couple of occasions it also offers enough of their trademark cartoonish eccentricity to more than ensure that they have not outstayed their welcome. Touch Yello: The Virtual Concert, meanwhile, is an impressively high definition hour-long performance film drawing heavily upon the new album but wittily incorporating a handful of older tracks and videos. It sees Meier and Blank dropped amidst a series of digitally created backdrops that veer from the melodramatic cinematography of an overly stylised perfume advertisement to the sheer joy of a madly inventive children’s television show. Throughout they gleefully interact with the scenery in a fashion perfectly suited to their music, a combination of James Bond, Blade Runner and Laurel & Hardy. It’s definitely more imaginative than Later…

Just to get to this interview Meier has had to fight his way through a throng of excited admirers, friends and family, none of whom seem to understand that in slowing him down they are merely prolonging his absence from a party he wishes to attend. But he has dealt with them all politely and gracefully, bestowing upon each one a little of his charm. Once he’s sat down, however, it’s clear that he’s not planning to stay long. He’s sitting here because that’s part of his job, and to be fair it doesn’t seem to be a part that he resents. But the no man’s land between journalist and artist remains untrampled and, it’s clear, will remain so for as long as he deigns to share his time. As he engages in a moment of banter while he awaits his Becks, it’s impossible to ignore the irises dancing in the vast white pools of his eyes, like those of a wild horse, unusually round and penetrating. But, though they could be fiercely intimidating, tonight they’re bright and friendly, betraying his excitement at what has taken place downstairs in the auditorium of the old East German Kino International. They dart from side to side, swelling when he wishes to emphasise a point, shrinking when he’s not sure he’s understood a question or, perhaps, is bored by it. And while he doesn’t incite fear – his air is jovial at the very least – he commands respect that only a fool would have the nerve to deny.

Dieter Meier has, after all, been doing this for a while now. Thirty years, to be exact. He and his musical partner Boris Blank (as well as, initially, Carlos Peron, who left after four years) have been releasing playful, intelligent, frequently groundbreaking electronic music under the name Yello since 1979. Within a year they had made their first impact: 1980’s ‘Bostich’ was a dancefloor hit feted by Afrika Bambaata that cast the mould for their distinctive sound, Meier’s absurdist lyrics – half spoken, half sung, not a million miles away from the simultaneously developing sound of rap – rattled off with an arched eyebrow while Blank constructed perfect pop from home made samples, heavily percussive rhythms, lush keyboards, an ever present Fairlight and sleek production standards perhaps only ever matched by Trevor Horn’s work for ZTT. This infectious, entertaining and unlikely combination has changed little since: Meier still spouts enigmatic or nonsensical lines in his trademark fashion while Blank has simply refined the sounds that have always lain at the heart of his music. There’s never been any need to mess with the formula because not only has it been successful, no one else has dared attempt it. But though they often appear inscrutable in photos, neither of them has ever been keen to appear over-earnest.

“In Yello we have a long tradition of, of course, loving what we’re doing very much but then also in a very serious way not taking it so seriously,” Meier states in English that is almost perfect but nonetheless scented with the accents of his Zurich home. “You know there’s always an irony and a self-irony aspect in it that was always what Yello was all about. I think people do like humour in Yello, and I think they do like the fact that there’s always something unexpected. They somehow get the feeling that these guys are two kids in a sandtip (sic) that have fun building their fantasy castles and these guys are always surprised themselves.”

That said, Meier is more than aware that for his musical partner Blank the making of music is an obsession. A perfectionist who started sampling sounds in the absence of any formal musical training, Blank constructs Yello music single-handedly, with Meier providing the melodies, lyrics and overseeing the manner in which the act present themselves.

“Boris,” he explains, “he is working in the studio on 60, 70 pieces at the same time, he comes to the studio every morning and then he continues brushstroke by brushstroke on a ‘painting’ and it’s really each stroke influences the next, and very often he starts with the idea of painting a rose and he ends up with a donkey. That is what somehow people enjoy, the unpredictable, and still within the identity of Yello. We’re obviously not great highly academically trained instrumentalists who then finally found a style. Our style came because we couldn’t do anything else… We can only be ourselves. We have no choice”

Blank is a notoriously quiet individual, blind in one eye after an accident with a firework in his youth, who rarely gives interviews. “Boris is an incredible comedian,” Meier elaborates. “He’s just so shy in front of an audience. But in front of a camera, or in front of people privately, he’s the most incredible joker”. Meier, however, has been happy to make up for Blank’s public absence. A larger than life character from a Swiss banking family, Meier has always enjoyed being the centre of attention but, acknowledging that his contribution to the making of their music is only a fraction of Blank’s, he is quick to rain praise on his colleague.

“I enjoy tremendously to be part of Boris’ sound pictures, you know,” he smiles happily, stroking a distinguished silver moustache that’s unusually full in the way that only Swiss or Germans dare wear. “I create the singing melodies of all the songs, I create the words. It’s always so inspiring that I can only thank Boris endlessly for creating these beautiful sound paintings for me. I think I wouldn’t be a singer, I wouldn’t be a musician, without him. I never really was a musician. He’s a natural born musician that was never allowed to play an instrument and used everything he could get hold of to make a sound. And I was always kind of dreaming of being this but without him I would not have created a single song. So it feels perfectly alright that I sing the song of Boris in Yello, but also for the press and whoever wants to know it, how really wonderful it is to be part of Boris’ music.”

His fondness for his musical partner seems wholly genuine, though one would hope so after three decades and well over a dozen albums, records that have allowed Blank to employ everything from the sound of racecars to lips being smacked. (Such is this alleged perfectionist’s devotion to his art that he is said to have amassed over 600 different samples of a saxophone alone.) But while international success has beckoned on several occasions, most effectively following the use of ‘Oh Yeah’ in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, and although they have had hits in both the UK and the US, their strongest territories remain those in the German speaking world, where the idea of Swiss pop stars fails to incite cynicism.

Yello have always been held in high regard internationally, however, with a 1995 tribute album including covers by the likes of Carl Craig, Moby, Carl Cox and The Orb. They have also collaborated with vocalists such as The Associates’ Billie Mackenzie, Stina Nordenstam and, on the elegant and unforgettable torch song ‘The Rhythm Divine’, Miss Shirley Bassey. But after such a long time one can’t help but wonder whether, trailblazers though they may have been, Yello remain relevant. Technology has caught up with them, so that while Blank continues to build his own sonic palette with his constantly growing sample library others are experimenting with sounds that he might only dream of. This, however, seems a pointless avenue to explore: if Yello were concerned about those looking to cast aspersions on their role in 21st century music it’s unlikely they’d project high definition images of Dieter Meier dancing like an aristocratic grandfather onto cinema screens.

“I think it’s funny,” he replies when asked whether it’s dignified for a 65 year old man to be carrying on like this, “and I’ve always sort of had a lot of self irony to whatever I do, and I think I will still be doing this when I’m 85. As long as it’s fun for me, and people seem to like it, I mean, I’d always do it. Maybe people at one point don’t like it anymore but I will still do it because it’s fun. Maybe I’m not a very good singer, but I’ve always been a very rhythmical person and I’ve always been a fairly good dancer. It doesn’t feel awkward to me, not at all. I remember all the movements.”

As it happens, he’s right. Though tonight’s audience laughed as he first strutted his stuff onscreen in an immaculate pinstripe suit at the film’s opening, it’s an affectionate approval they’re exhibiting, respect for Meier’s love of the absurd. But perhaps the thing that sets Yello apart the most has not been the childlike pleasure their music both inspires and enjoys, nor their arguably pioneering use of samples, not even Meier’s unique vocal delivery, part LL Cool J, part Lee Hazlewood. It’s been their refusal to operate within the usual parameters of what kind of background is ‘acceptable’ for a musician. For starters, there’s Meier’s life as an art prankster: he has rolled balls of gold 12 metres, failed to show 18 exhibitions called ‘Lazy’ – “it was a great idea but then I forgot about it” – and written a book featuring blatantly faked pictures about his ascent to the top of a mountain, El Monte Dorado (2007). Most famously of all, in 1972 he installed a plaque in Kassel, Germany’s main railway station with the inscription, “On March 23 1994, from 3 to 4 pm, Dieter Meier will stand on this plaque.” He did.

More importantly, however, on top of – or most likely enabled by – his privileged and wealthy background, Meier is also an aesthete who has designed silk scarves, excels at poker, runs a 2200 hectare cattle ranch in Argentina which supplies the Zurich restaurant he owns and who has played for the Swiss national golf team. Significantly he has never kept any of this secret from anyone. His whole methodology revolves around a consummate blend of statement, art and music, laced with a worldly frivolity. In a musical world in which questions of authenticity dominate, in which Joe Strummer can be condemned for his private school education – something over which he had no choice whatsoever – and Pete Doherty can be lauded simply for his grimy fingernails and needle-perforated arms, Meier is next to unique. The man doesn’t even swear, something decidedly unusual in this line of work. In fact his upper class background and refined appearance are as much a part of his public persona as Elly Jackson’s wonky hair is part of La Roux’s. Few other people could get away with this: Genesis were always treated with suspicion for their private school roots, and Keane have been frequently ridiculed as “posh”. Meier, however, has confronted this prejudice straight on, even posing with his golf clubs for Melody Maker around the release of One Second in 1987.

“I think it’s being honest and true to this situation,” he theorises when asked how he has got away with this. “I know a lot of artists who have still this situation and first of all it’s quite difficult when you come from such a family, you know, that you don’t have to fight your way through society in order to survive, it’s quite difficult to do anything. You could as well go to Hawaii and pretend you’re writing a novel for fifty years and if you don’t finish it, who cares, you know? So that’s why it’s difficult to kind of find yourself and find your form and find your reason to be when there’s no immediate need to do anything. And I was always just very honest about this. I never pretended to not come from such a situation. I never pretended to have separated from my family. I love my parents, I always loved them, and of course they sometimes didn’t quite understand what I did, especially as an artist, you know. But we were always very close, and, I mean, to have certain possibilities, then it’s a great thing to use them and to be honest about them. Simple as that. And most people in the art world, in the music world, and especially in the political world, they feel ashamed that they come from that background and then they’re being called saloon communists or saloon artists and not being taken seriously. And indeed, at the beginning of my first steps, a lot of people always commented, ‘Well, if I came from that background I would do even much crazier things, and this guy can afford it’, and there were even people who said, ‘Well, his father bought him the way into Warner Brothers, his father bought him the way into Documenta’, and when you’re young that hurts. Now I couldn’t care less.”

He leans back contentedly in his seat and grins, his saucer eyes ablaze again. “Some guy, as I was always writing for philosophical papers and essays and magazines and stuff, said ‘Dieter, I’m not going to print this, but can you tell me who writes these essays for you?’ I said, ‘Look, guy, I have two intellectuals at home in my basement. They like to eat bananas. Whenever I want an essay of substance” – and here he whispers conspiratorially – “I give them more bananas and they think harder, and then they deliver this most wonderful text that I pinch from them and publish it under my name.”

And with this final display of the irony he loves so much, Meier accepts his record company employee’s suggestion that the interview be wound up, straightens his jacket and bids The Quietus farewell with a firm handshake. Aesthete, prankster, artist, restaurateur, organic farmer, golfer and the voice and public face of one of pop music’s greatest, if undervalued, treasures: Dieter Meier has plenty to celebrate, and the festivities await. It’s his party, after all, and after thirty years it’s far from over.