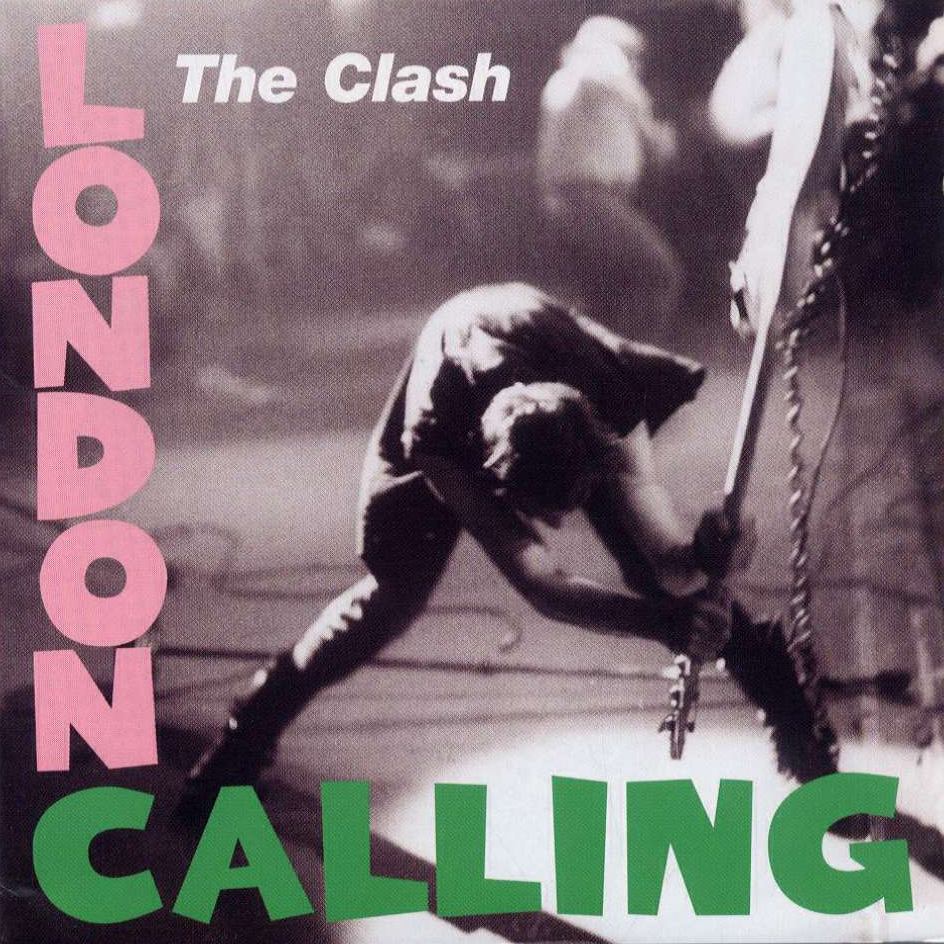

December 14th, 1979: The Clash release London Calling just in time for it to be safety-pinned to every punk’s Christmas wish list. At the affordable price of £5, the double LP peaks at number nine in the charts and is certified gold the very same month. It’s lauded in the press, placed on a pedestal labelled "Zeitgeist" and hailed for its social narrative, political articulacy and (relatively speaking) experimental roots.

December 14th, 2009: London Calling marks its 30th Anniversary. Its legacy is once again remastered, repacked and resold to a new generation for corporate gain. For an album that defined an era of rebellion and social change, have any lessons been learnt from its virtuous, defining narrative? Or had the band diluted punk into something more palpable, and dare I say it, pop, as means to drag its stubborn and stumbling carcass of thought and philosophy into another decade of disillusion and disappointment? Did anyone listen to its message, or was it simply the final shout of the 70s only to be replaced with the more conservative rock and roll of the 80s and beyond? Has London Calling‘s legacy and inspiration been defined in the slew of landfill indie of the past decade, and not the experiment dub percussiveness that it (partially) embodies?

Mark Perry of Sniffin’ Glue famously quoted that punk died the day The Clash signed to CBS January 25th, 1977. The band were perpetually questioned over the issue as they moved away from their DIY roots and anti-establishment stance so they could indulge in ‘getting the message across’ to a wider audience. To say that punk had died is questionable. First wave UK punk was nihilistic and would always implode, but if change was to be established within its myopic stare, it had to reach out as far and as fast as possible. The Clash may have sold out, but they did it with a cause in mind.

After their eponymous debut, 1978’s Give ‘Em Enough Rope and the firing of manager Bernie Rhodes, a new rehearsal space was found at Vanilla Studios, in Pimlico, and The Clash began work on what was to become London Calling. The absence of Rhodes meant that there was no more of the hectoring, plotting and obfuscation that they had become used to, and as a result the group found a new sense of freedom. The atmosphere was energetic, productive and inclusive; stylistically there were no boundaries.

The Clash began to experiment with different strands of jazz, soul, funk, reggae, skiffle, rock and R&B, as they found a new sense of urgency in what they were writing. This feeling was intensified when Guy Stevens was brought in to produce the album. An unpredictable and volatile individual, he would often smash chairs and cause destruction and confusion around the band as they recorded, as if to amplify the passion.

Thirty years on, and London Calling is still seen as The Clash’s finest hour. The album’s opener, and title track, sees the band move away from their somewhat restrictive roots and march to a different militant beat – their own. The band had never felt so unified up until this point, and with the arrival of Thatcherism, their third album was a necessary voice that countered the new Conservative Government from the heart of the Top Ten.

Rhythmic and rasping, the Em/Fmaj9 riff that unleashes ‘London Calling”s war cry sets an ominous tone to the record. Stabbing guitars, stuttering base and then the opening lines: "London Calling to the faraway towns/Now that war is declared – and battle come down." The theme of the album is set, as Strummer continues to declare among a number of caterwauls, "The Ice Age is coming, the sun is zooming in." Polemic, political and apocalyptical, it sees The Clash at their most formidable.

However, the problem with London Calling is in its inconsistencies and incoherence. For what is seen as a "brave" album in the context of its time, there is little that links each track to the other in form and fluidity. The shuffling rigmarole of Vince Taylor’s ‘Brand New Cadillac’, and the crapulous slur and turgid bass-walk of ‘Jimmy Jazz’, are only to be saved by the Bo Didley-like ‘Hateful’ at the start. It’s the aural equivalent of a trifle: somewhat confused as to what it is, ingredients and influences have been thrown into a bowl with a lack of care and clarity, but a whole lot of enthusiasm that tries to cater for every taste.

Then there are the awkward moments: ‘Lover’s Rock’ sees Mick and Joe bumble, simper and croon uncomfortably about love, sex and the pill; the litany of failure that envelops ‘Death Or Glory’; and the arrogant self-prophesising and mythology that serialises the band as the ‘Four Horsemen’ of the apocalypse.

It’s only when they resurrect their punk roots in the form of ‘Clampdown’, ‘London Calling’, ‘Koka Kola’, ‘Hateful’ and the pop twist of ‘Spanish Bombs’ that they are at their uncompromising and inimitable best; or when they really stretch themselves with the terse and edgy dub percussiveness of ‘Guns of Brixton’ by Paul Simonon.

For the price of a Lady Godiva, the double album was sold as a single – the second slab (featuring nine tracks) was given away as a free 12" within its gatefold – the band saw this as their first real victory over CBS. But in their wish to give more to their audience via a Robin Hood ideology means London Calling didn’t provide enough sustenance for many who had loved their first two albums. It is spirited and human but, due to its jumbled density, flawed.

The double album is now being held as artefact that today’s Young Turks often hail as a blueprint for societal change via musical endeavour without consideration for these flaws. Many see it as their best, but I can only see it as their most progressive.

Instead, the only lessons that appeared to have been taken from The Clash’s career up until this point was not to sign a contract like the one with CBS. For their initial victory over the formatting of London Calling, the band were faced with having to fund most of their tours and recording themselves, and they remained in debt to the record company well beyond their split in 1986.

Two decades on, and we’ve lately seen a new scene of bands all inspired by the punk movement of the late 70s, and especially The Clash. The link between The Libertines and The Clash was cemented when Mick Jones produced Up The Bracket, but Doherty and Barat’s tribute was a misinterpretation. Instead of partial musical radicalism, they took inspiration from the fashion, a pseudo-DIY ethic, an abrasiveness, a fanatical following, a sour demise.

In their wake, a burgeoning scene of replicants spilled out from the sleazy Rhythm Factory in the east of the capital, with Doherty himself acting as a deity and Pied Piper to a generation of scuttering twits. Record labels duly threw money and publicity at those bands scurrying beneath the pallid detail of Doherty’s trench coat and lifestyle, as the NME bolstered its support for this new breed with a four-page dedication to the DIY scene: ‘The Future Starts Now!’ (August 7th, 2004).

The ‘Future’, as expected, was as ephemeral as Doherty’s bathing routine. The likes of Thee Unstrung, The Others, Neil’s Children, Dogs and The Paddingtons all suffered commercial comedowns following their rush, with The Rakes and Babyshambles grimly hanging on for a few more years after their well-received debuts. What Ever People Say I Am, That’s What I Am Not by the Arctic Monkeys has possibly been the only album of this decade that has touched on the rhetoric and dub influence of London Calling as well as its mainstream rock/punk bluster. Yet even this is terribly conservative in comparison to The Clash’s back catalogue.

London Calling was the swan song of the 70s. It laid to rest a decade of dischord with a diluted form of punk’s ideology that was aimed right at a wider audience. The passion can still be felt through the 19 strong songs, but it appears that their original message has fallen upon deaf ears due to its length and musical progression. 2009 has been very similar in many way to that of 1979: high rates of unemployment, lack of opportunities for a disillusioned youth, and politicians who are more interested talking about change than doing anything about the situations that we face.

Are we due a renaissance of punk ethic and leftist political ideology in modern music? Maybe: musicians have as much, if not more, cultural leverage in today’s society than any political figurehead, and as we stumble purblind into what looks set to be another turbulent decade, I personally feel a need for a rhetoric that echoes the concerns of the disenfranchised many. In their time, The Clash mapped out a sense of revolutionary optimism. It’d be something that could inspire a future and dialogue with the new to grab onto instead of mere conservative straws to clutch at.