This week Dr Rock is chewing the wurst with Michael Rother from kosmische pioneers Neu! and finds out the truth about turning down Bowie, playing ping-pong with Eno, rocking out to Fuck Buttons, crossing Neu! with The Beatles, making peace with Klaus Dinger, and all things Cluster, Kraftwerk, Can and Harmonia. All hail!

You grew up in lots of different places. How did it shape your musical tastes and your outlook on life?

Living in Pakistan was a very special step for me because I got in touch with culture from outside of Europe for the first time. There were bands in the streets playing this monotonous and endless music and I remember the very special feeling I got from listening to that. And that’s probably one of the roots of my interest in that repetitive approach to music that seems to want to go on forever.

I was born in Hamburg, and then moved to Munich at the age of four and to England at the age of nine. I have very wonderful memories of my 11 months in Wilmslow, near Manchester, but I think the impressions I got from British music came later. We went to Pakistan when I was nine, in 1960, and we stayed for three years. From there we moved to Düsseldorf where I stayed until I left to move to Forst where I am right now, actually (laughs).

What music inspired you when you first picked up a guitar?

I have a brother, he’s nearly 10 years older, and it’s through him that I got in touch with all the rock ‘n’ roll greats like Little Richard. I still feel very thrilled whenever I hear Little Richard’s music now. The same of course goes for the other rock ‘n’ roll giants. I was very young so it was a very emotional impression I got from listening to that music. The wild character of rock ‘n’ roll music is probably one of the elements that contributed to shaping my idea about music but talking about the sources, I have to mention my mother who played classical piano when I was very young. I actually don’t have memories of listening to her playing because when we left Hamburg we couldn’t take the piano with us, moving around the world all the time. But she told me in later years that her favourite composer was Chopin. She was classically trained and I grew up having those waves in the house, the atmosphere of European classical music.

But you asked about the guitar. I remember when my brother visited us in Pakistan, he brought along new singles and one of them was a track called ‘Apache’. It was also played by The Shadows but he brought a different version by a Danish guitar player called Jørgen Ingmann. It really appealed to me and I had a sort of, I don’t know what the English name is, Japan banjo perhaps or Nagoya Harp. It’s like a typewriter and has maybe 8 or ten strings and you play different keys by pushing the keys of the typewriter and you can play an octave through that. I tried to modify that instrument into a guitar and of course I failed at that. I think dating from that period I was attracted to guitar–playing. When I lived in Düsseldorf and I had friends who already were in a band, I got a very cheap guitar at home and I think I must have driven my mother nuts playing guitar all day long but my mother didn’t say anything because she loved music so much and even though her training went to a degree that she could have performed classical concerts, she never had the opportunity to live the life as a musician. She had to work in an office to make money. It was a difficult period of time in terms of the economy in Germany back then. I think she had all the understanding that was necessary to let me scratch on the guitar all day long. She didn’t feel annoyed by that.

Then I bought an electric guitar and I started to copy all those heroes, the new bands, especially the ones coming from England, the Beatles, The Kinks and The Rolling Stones, of course. Later I moved on to Cream and after that Jeff Beck was a great guitar player for me and also of course Jimi Hendrix changed everything. When Jimi Hendrix came along it was a completely new situation, like something falling from the stars.

Can started out in 1968. Did they make an impression on you then?

I didn’t hear about Can until I met them when I was with Kraftwerk, in ’71. It was quite funny because they had a similar problem to Harmonia in that when playing live, they were sometimes not capable of finding the right idea. It’s obvious, they have magic in their music on albums. Songs like ‘Yoo Doo Right’ still create magic. Especially Jaki Liebezeit, he’s amazing! But when we played together they didn’t impress me because they didn’t have one of their good nights. Of course I found out about their music properly later, I heard at least ‘Monster Movie’ but I didn’t know it at that time. I had then stopped listening to other bands, other artists. That was necessary to avoid being influenced by other people’s ideas. It was a time when I was very carefully shaping my own views on music, shaping my ideas. I was focused only on my own personality, on my own approach to music at the time.

That’s quite interesting to me since a lot of bands in Germany at the time would live in communes and make music together

Well that’s true but I chose the people I collaborated with. So of course the musicians in Kraftwerk, my colleague and partner in Neu!, Klaus Dinger, my partners in Harmonia, those were the people who inspired me, who influenced my thinking about music. They were the partners with whom I exchanged ideas and tried to develop my approach to music. But outside of these bands and projects I was involved in… It always sounds a bit strange, maybe big headed but I wasn’t interested whenever I heard something I wasn’t that impressed with. I just realised they were on a different voyage to somewhere else and that wasn’t my way so I didn’t follow it any further.

How did you meet Neu!’s drummer, Klaus Dinger?

When I stumbled into the Kraftwerk studio in ’71 by chance, Klaus was one of the guys performing with them. He was already on a few tracks of the first album. I’d been jamming with Ralf Hütter actually; that was the first time I’d met someone who had a similar approach to European music that was free of the blues. We didn’t talk about the reason why we chose certain notes and avoided others. It was apparent that we had a similar taste. Then a few weeks later Florian Schneider called me and asked whether I wanted to join Kraftwerk. That was with Klaus Dinger on drums and it was the first time I saw him play. And it was really amazing. He was such a radical person, he was so engulfed in music. At least at one concert, but it may be true for more than one, he cut his hands at the edges of broken cymbals and blood was gushing all over the stage. There was blood everywhere and people’s jaws were dropping. He didn’t stop for a moment, he just kept on beating the drums with the same impetus.

The atmosphere in Germany in the early to mid 70s was quite tense what with the Baader Meinhof terror, student uprisings and so on. How did this political mood affect the music you played?

All the upheavals, they left an impression upon my thinking about society, about politics and life, culture. There were all these new artists coming up with new ideas, people like Fassbinder, etc. and of course political figures like Willy Brandt and his approach to re-configuration with the East, that was something that really impressed me. Of all these turbulences in society and politics shaped my thinking, of course. I was a conscientious objector. No force in the world would have made me go to do the military service in 1969 and I think all of these changes in combination with my interest in psychology and some other sources all these ingredients – I can’t say for sure but it’s obvious that all these impressions in the political and cultural scene and in combination with my interest in psychology made me arrive at that point where I understood that I had to create my own personality, I had to define my own musical personality also and all of these occurrences like Baader Meinhof, they were even worse in later years. The real terror by these lunatics, they were certainly not on the right road for me at least, that happened in 1977, it was called the German Autumn, where they killed several people like Hans Martin Schleyer. But in the late ‘60s we can’t neglect the Vietnam War, the idea of cultural dependency, of freedom from this cultural dominance in which we had had grown up and the Anglo-American music and culture, of course.

What was the concept behind Neu!?

We didn’t have a concept, we didn’t discuss theories. Klaus and I never sat down and talked about what we should try to create, we just did it. I think we both had the impression that our ambitions were similar. Certainly there were differences in the visions that Klaus and I had. But whenever we made music it just worked. Looking back at the way we recorded the first Neu! album, for instance, so many elements were put together in a very short span of time. We didn’t even get the opportunity of making any kind of sketches before we went into the studio, for example. We just reacted to this situation, we reacted to the contributions the other one offered and moved on, very fast paced. So it wasn’t the idea of recording endless hours of music and then choosing minutes of it. There’s hardly any material recorded, in the 70s, that hasn’t been released. We were very economical.

Did you play a lot of concerts around then?

Not in the 70s with Klaus. That was one of the big problems we had as Neu!, being only two people. We did try to do concerts in ‘72 and that didn’t work at all. Just one guitar and one guy on drums, that didn’t take us very far. I even tried to use a tape with some pre-recorded sounds, bass, etc. But people hated that at the time. It wasn’t accepted as real, authentic music if it didn’t happen live on stage. And then we tried to add some musicians to our live line-up but didn’t find any suitable people. We tried Uli Trepte of Guru Guru and Eberhard Kranemann who had been with Kraftwerk for a time but both weren’t the right people. That actually was the reason why I visited Cluster because I was looking for people that were suited to help us put Neu! on stage. I took my guitar and went to Forst in the spring of ’73 and ended up jamming with Roedelius. He played on the piano and I played on my guitar and it was beauty on the spot, it was amazing, it was something I hadn’t experienced in that intensity before, except in combination with Klaus on drums. But to play melodies and sounds and the special way Roedelius worked the distortion and delay, that impressed me. Just the piano and my guitar sounded really beautiful. So that was why I decided to stop Neu! and start Harmonia instead.

How did Klaus feel about it, was he ok with you stopping the band?

Of course he was quite upset about that. He actually tried to convince me to work with him again and he also visited Harmonia. One of Klaus’ ideas later was to create a group of his which went on to become La Düsseldorf, with Harmonia. In theory, that was a great idea, to have the power of two drummers and the space of Harmonia. But that was just a theory unfortunately. Klaus was such a difficult person and everybody hated him. He thought he was on a road to superstardom and acted like that, in a way. Anyway, it was just decided, on a personal level, that we didn’t want to go down the same road. So he left. Of course Klaus and I met again in ’74 to record Neu! ’75. And I wouldn’t have wanted to miss that; some of the best music I was involved in certainly was on Neu! ‘75.

Talking about David Bowie, as far as I know he even called his album Heroes after your track Hero from Neu! ’75

I think so. I didn’t talk to David about that when he called me in ’77 and asked me if I could join him in Berlin. We were just talking about music we wanted to do together but I know from some interviews that David Bowie gave as well as from talking to Brian Eno, that they were discussing all of our albums. David also said, I think in more than one interview, that tracks like ‘Hero’ and ‘After Eight’ were some of his favourite music so I think it would be fair to assume that he took that as inspiration not only from our music but also for naming the album. And that was actually the album we would’ve done together if somebody hadn’t tricked us.

What do you mean?

Oh, you don’t know the story? Well, there’s some mystery about what happened in ’77. For many years I believed that David Bowie had changed his mind. Which was what someone from his team told me. David and I had discussed details about the music, etc., instruments I should bring along. We were both very excited about that. But then someone else called me and said ‘I have to tell you that David changed his mind, you don’t have to come to Berlin after all.’ So that’s what I believed. I was busy with my solo career at that time, my first solo album was suddenly taking off, and I started recording my second solo album the same year. So I didn’t cry for a long time. I was just puzzled because I thought that didn’t sound like what we’d been talking about, but who knows? It took about 20 something years until I stumbled upon interviews David Bowie gave where he said ‘I invited Michael to record with me but unfortunately he turned me down.’ My guess at what happened is that people in his team where a bit anxious – sales were going down because his experimental approach to music wasn’t commercial enough, his fans wanted a continuation of the Ziggy Stardust era. It’s so strange to me that 20 or 30 years later his three Berlin albums are considered to be his best by many fans and critics. But at the time it was different. The sales were dropping considerably and maybe it was decided that David Bowie would make better pop music without another German guy as inspiration on his team. It was strange 20 something years later to hear him tell a very different story. But it’s no use now crying about the fact that Heroes was made without my guitar and without my input. But who knows, maybe I would’ve destroyed the album.

But you did end up recording with Brian Eno who was also a huge fan of yours. How did that come about?

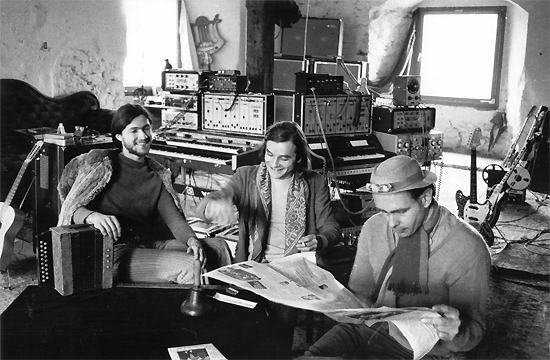

Brian suddenly sat in the front row of a Harmonia concert we played in Hamburg in ’74. I think he was on a promotional tour in a town nearby and the German journalist who interviewed him was a fan, one of the two fans we had in Germany (laughs) at the time. Brian told him about all the German music he listened to and loved – Kraftwerk, Harmonia, Neu!, etc. and so this journalist guy told him’ yeah, they’re playing in Hamburg tonight’. So that’s why Brian ended up at that Harmonia concert and he joined us on stage. We talked and got along very well and we invited him to visit us in Forst. But that didn’t happen for two years. In ’76 he suddenly called and asked ‘would it be ok if I came to visit you now?’ So that was the situation. Funnily enough we already had split as a band, Harmonia had split in the summer of ’76 but of course we didn’t want to prevent that project from happening and him from him visiting us. So we all got together and spend 11 great days talking, walking, playing ping-pong and also recording music. That’s my recollection of what those days were about. Not necessarily in that order but it was so relaxed, it was such a great creative atmosphere, there was no pressure. The idea wasn’t to record an album but to exchange ideas, to create something. We recorded all those sketches on my four-track machine, Brian had brought some blank tapes along and that was the story.

What’s coming up for you?

Well, Harmonia have stopped playing live again, that project has come to an end. I’m so busy, I think I’ve never been so busy in my live. If I look at the recent month with all the interviews, there’s been such a surge of interest. The BBC just made a documentary about German music of the early 70s and the German / French TV station Arte are also working on something and there’s people writing books about Krautrock. It’s amazing, it’s such a huge change. I’ve experienced, as I already explained, very different times with no reactions in the past. So now I’m very happy to explain what I can and it’s great to see our music being resurrected all around the world.

The next project that I’ve been working on in recent weeks and months is the release of a Neu! vinyl box-set. That’s a big and very ambitious project. The idea is to put the originals into the box and also to add a legal version of what Klaus Dinger released in Japan in the ‘90s, the Neu! 4 and Live ’72 albums. I also have some more material which Klaus didn’t have. It’s a very unhappy story. At the time he was so desperate and paranoid that he just send me a fax in ‘95 saying, ‘congratulations, Neu! 4 is out in Japan tomorrow.’ I don’t know if he thought that was funny. Of course I didn’t. I tried to have a proper release of the material with him but we didn’t manage to do that, it was impossible to find an agreement with Klaus. He was desperate for cash, etc. But now we have a different situation. His widow, his last companion, she’s very cooperative and I’m working on all of the music we recorded. Some of the tracks are not known to the public.

I think I can do a better job than what was released by Klaus, to showcase what Neu! were capable of doing in the 80s. It’s a different story, compared to the originals of the 70s. There are some faults. When we met for what we called Neu! ‘86 at the time we both had studios and we both had an unlimited supply of time. Unfortunately we spend too much time having foolish fights over details which didn’t bear any significance for the music. But it’s an interesting document and listening to all the recordings we did I felt much closer to Klaus again because I remembered the positive sides of his craziness, the artistic person he was, without all the ego problems we had. Just to be able to concentrate on the music was something I very much enjoyed. In a way I had to get used to listening to his voice again, talking. He died last year so that of course changed everything. I think it’s very important to show all of the music Klaus Dinger and I did and that’s the idea behind that vinyl box-set project. It will also feature a 12 inch vinyl sized booklet containing lots of never before seen photos and texts about Neu!. I think it will be a very interesting item for fans.

Did you manage to make your peace with Klaus before he passed away?

I wasn’t aware that he was ill, that he had problems with the heart. We didn’t communicate on a regular basis at the time so we didn’t find an agreement, really. We’d met several times since 2000 and we’d talked about recording a new Neu! album which the company wanted to release and also Klaus really wanted to do. Klaus actually around that time really wanted to tour the world as Neu! I was always very sceptical but I would lie to say that I regretted having been so cautious. It was necessary to be cautious. I may have prevented some things happening but I had my reasons. But to make peace I think is also possible now and like I already said, it’s concentration on the great artistic personality and really being happy about having had the opportunity to have worked with Klaus, having been able to create all that music, also with Conny Plank, of course, we must never forget him, he was a vital third member of the band. In a way I have made peace with Klaus on my own and maybe he’s aware of it.