For Salvador Dalí: a toilet made from intertwined dolphins — one mouth to receive piss; the other, shit — and $100,000 an hour to play the Emperor of the Universe. For Pink Floyd, Gong and Tangerine Dream: a planet each. For some of the then unknown, now best-known sci-fi and comic book talent in the world: the opportunity to do whatever they want under the guidance of a cinematic visionary. For the human race: enlightenment.

Director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s plans for a film of Frank Herbert’s epic sci-fi novel Dune, it’s been suggested, may have been a little too ambitious to come off. But they came damn close: two years of pre-production work and two million dollars were spent before the plug was pulled, during which time Jodorowsky’s team of ‘seven samurai’ forged productive alliances and pushed the look and feel of sci-fi cinema forward. Effects man Dan O’Bannon would go on to create Alien with the artists hired; Jodorowsky and Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud would rework much of their Dune into the hit French comic book series L’Incal.

If ever there was an unfilmable novel, it was Dune. Spanning

generations and planets, portraying complex fictional dynasties and hidden identities, and drawing on Islam, Buddhism and environmentalism, it seems it was simply too vast a prospect to be realised successfully onscreen (or summarised here — see the wiki for an overview). Arthur P Jacobs, producer of Planet of the Apes and Doctor Dolittle among others, had planned to film Dune with David Lean, who declined; Jacobs was nevertheless set to begin filming when he died suddenly of a heart attack in 1973. Herbert himself then attempted a screenplay, but ultimately had to throw his hands up and accept that it was a disaster. Ridley Scott would pick up the baton for a year after Jodorowsky’s attempt folded, but drop it again to make Blade Runner, balking at the prospect of the three further years’ work ahead. The messy Dune we know and half-remember for Special Agent Dale Cooper riding giant worms and an unconvincingly villainous Sting finally emerged in 1984, heavily edited by the de Laurentiis producers. It would soon be disowned by its director, David Lynch.

Perhaps the only sane approach to filming Dune would be to create your own myth inspired by it, as Jodorowsky intended: “I did not want to respect the novel. I wanted to [reinvent] it. For me Dune did not belong to Herbert as Don Quixote did not belong to Cervantes.” And there have been few figures in cinema better suited to the task than Jodorowsky.

Opening up his world to the newcomer is a challenge perhaps best met with a quote from the man himself: “I’m extremely attracted to what I don’t understand. My intuition tells me that there lies something important to study.” Born to Russian Jewish parents in Tocopilla, Chile in 1929, he became a published poet while still in his teens, working alongside future Nobel nominee Nicanor Parra; studied philosophy and psychology in Santiago while also running a large theatre company; left to pursue an interest in puppetry; moved to Paris to master mime alongside Marcel Marceau and direct his film debut, La Cravate (praised by Jean Cocteau); founded the Panic movement with playwright/director Fernando Arrabel and cartoonist/author Roland Topor, whose theatre happenings — provocations intended to reclaim Surrealism from its stuffy old guard — would involve snakes strapped onto torsos, crucified chickens, and giant vaginas giving birth to actors; directed, wrote and acted in over 100 plays in Mexico City (his Godot got him vilified) while also working in mainstream Parisian theatre (at one point directing Maurice Chevalier’s comeback); and contributed the weekly, subversive Fábulas Pánicas comic strip to the reactionary Heraldo de Mexico newspaper (it was too popular to drop by the time they twigged what was going on).

A Panic happening (anti-explanation by Arrabel; explanation by Jodorowsky)

Summarising Jodorowsky’s cinematic style is even harder: there really aren’t many illuminating comparisons to be made. (David Lynch if he switched to decaf? Kenneth Anger if he’d got past the occult to embrace a fuller history of ideas, psychology and symbols, with a healthy dash of humour?) His genius lies in making cinema do things no one suspected it could; his attraction to the unfathomable has led to some of the most original and engaging storytelling in the history of film. 1968’s Fando Y Lis was very much part of Panic: a wild step on from Samuel Beckett via Jodorowsky and Arrabel’s brand of surrealism. Our protagonists (paraplegic Lis and her betrothed, Fando) roam cemeteries and wastelands, taking in burning tarantulas and pianos, real-life vampirism, sexually predatory pensioners and a pride of bowling ball-wielding drag queens along the way, in search of a mythical city called Tar where all dreams come true. There was a riot at its premiere, and the film was banned by the Mexican government.

But it was in El Topo that Jodorowsky really found his voice. The influence of Ejo Takata, the Zen Buddhist monk who trained him in the ways of the koan and meditation, is notable throughout, alongside the vast library of literary, artistic, philosophical and religious ideas Jodorowsky had consumed. The joke is that he set out to make a Western and ended up making an Eastern; the reality is both stranger and more kick-ass. The first half mixes aestheticised bloodbaths and exploitation film thrills (plus a black leather get-up inspired by Elvis’s ’68 comeback) with Buddhist, Sufi and Christian-styled soul-searching. The second pits a small-town society steeped in capitalist and religious corruption against a caste of disabled outsiders liberated from their underground lair by a reformed El Topo. Jodorowsky has always hoped that the making — and viewing — of his films will be a life-changing experience; this one seems to have captured his own progress from the culture of the machista he grew up with to a more enlightened outlook. It became an unlikely underground smash, establishing New York’s ‘midnight movie’ scene and impressing John Lennon so much that he persuaded Beatles manager and counterculture tycoon Allen Klein to buy it and release it properly.

Lennon’s influence also secured Jodorowsky a million Klein clams to make his next film, the peerless The Holy Mountain. Before we go on, it should perhaps be emphasised that Jodorowsky has never been a drug user, nor anything other than a fierce critic of all religions; yet by this point he genuinely did feel as if he was on a holy mission. He wanted his film to both document and become a transformative experience — to be the tab of LSD itself (as he pitched it to the hippies) rather than to depict the drug use or drug-induced visions his new audience of stoners might be more at home with.

The results were spectacular: an end-to-end riot of colour, emotion and sensation, frame after frame packed with powerful symbols, not to mention pop art, fashion and set design that far outstrips even Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. If it’s a take on a genre, it’s very loosely the ‘Berg’ (or mountain-climbing) film. But that’s just underneath somewhere, providing the momentum; there’s simply nothing else like it, anywhere. The Holy Mountain is populated throughout by Jodorowsky’s people — the disabled, the homosexual, the dissident; everyone, in short, who would have been classed as degenerate or undesirable by the Mexican authorities of the day. You also get the Jodorowskian menagerie: peacocks, tigers, apes, hippos, pelicans and camels; even chameleons and toads dressed as Aztecs and Spanish conquistadors. If he’d only managed to film the bravura, almost dialogue-free 40-minute opening sequence we’d still be banging on about it here. With judicious editing of the middle section, it could have taken off and made a multitude of converts. As it stands, The Holy Mountain is the most incredible director’s cut you will ever see.

So you can understand why Dune appealed to Jodorowsky: a synthetic myth of that scale would seem the ideal playground for his syncretic imagination. Following The Holy Mountain’s cult success in 1973/4, he’d actually hoped to make Mr Blood and Miss Bones: a pirate film for children based on the voyage of Saint Brendan, set and shot (in a boat!) on the streets of NYC. (“Pirates were true examples of anarchism . . . and pirate women were the first to proclaim women’s liberation,” he explained.) Klein steered him in the opposite direction: ‘adult’ films had become fashionable in the era of Deep Throat and Emmanuelle, so he lined Jodorowsky up to adapt and direct Pauline Réage’s dom-sub tome The Story of ‘O’. Jodorowsky did a runner from a London meeting in which he was to be given a $200,000 cheque to seal the deal, and flew immediately to New York. “I am a feminist,” he later said. “I didn’t want to make a picture about a woman who is a slave.”

And that was the end of his relationship with Klein. Or rather, the birth of Klein as Jodorowsky’s long-serving nemesis. Klein seized all prints of El Topo and The Holy Mountain, and would refuse all requests for screenings over the next 30 years. Jodorowsky would personally donate VHS copies to pirate distributors in every new country he visited; Klein would weigh in with a heavy lawsuit against those distributors. Jodorowsky would tell interviewers that Klein deserved death for killing his films; Klein wouldn’t budge.

Upon arrival in New York, Jodorowsky called Michel Seydoux, the French producer who’d launched El Topo and The Holy Mountain in Paris, to pitch a new idea. He would direct the film of Frank Herbert’s novel Dune — which he had not yet read. Immediately, he packed his family and belongings up and flew to Paris, where he’s lived ever since.

Many intriguing names were attached to the project. Orson Welles was in line to play the ultra-corpulent Baron Harkonnen, who can only move when he has anti-gravitational balloons attached to his limbs. Gloria Swanson (Sunset Boulevard), Mick Jagger, David Carradine (known then for the Kung Fu TV series and now for Kill Bill), Geraldine Chaplin (Dr Zhivago) and Alain Delon were in line for other parts. Each planet in the film would have its own designer and score. Reports suggested that the running time could be anywhere up to 10 or even 14 hours. You can read Jodorowsky’s own account of the Dune experience here, but the main players were as follows.

Salvador Dalí was cast as the insane Emperor of the Universe, who lived on an artificial planet built from gold and had a robot doppelgänger – actually conceived as a way around the real Dalí’s extortionate fiscal demands for appearing in person – to keep people guessing, fearfully, which one they were dealing with. He accepted the part with apparent glee, his only demand being that the Emperor’s throne must be a toilet made from intersected dolphins, the tails forming the feet and the mouths to receive piss and shit separately. (He thought it terribly bad taste to mix the two.) Dalí then insisted that he be paid $100,000 an hour to sit on it. He also deemed it essential that we see the Emperor defecating and micturating in the film — but a body double would have to do that for him.

Following various dinners with Dalí’s entourage, who included at the time Mick Jagger, Pier Paolo Pasolini and “an enormous, virile Dutchwoman who posed while Dalí combed her sex”, Jodorowsky handed Dalí a tarot card (The Hanged Man). This was their contract. Only able to secure $150,000 — enough for one-and-a-half hours of Dalí — Jodorowsky created the plastic robot double and reduced the painter’s script to a page and a half. Accounts of what happened thereafter vary, but according to Brian Herbert (son of Frank) real-world politics impinged unpleasantly. Dalí had long been a vocal supporter of the Franco regime back home in Spain, and dug himself up to the neck with public pronouncements following the execution of political prisoners in September 1975: “there’ll be no more terrorism because they’re going to be liquidated like rats. Three times more executions are needed.”

Jodorowsky, who’d received death threats from the Mexican authorities and memorably depicted their massacre of students in The Holy Mountain, had apparently had enough. He announced to the press: “I would be ashamed to use now in my work a man who in his masochistic exhibitionism demands the ignoble death of human beings.”

The director headed for England to find the right musicians. Each band chosen would have its own planet to soundtrack with a suitable style of music. Virgin offered him Gong, Mike Oldfield and Tangerine Dream; Jodorowsky asked, “Why not Pink Floyd?” Fans of El Topo, they agreed to meet while recording Dark Side of the Moon. Greeted by the sight of the band stuffing their face with steak and chips, Jodorowsky stormed out only for Dave Gilmour to run after and placate him. They ended up agreeing to provide most of the music for the film, and to record a double album called Dune.

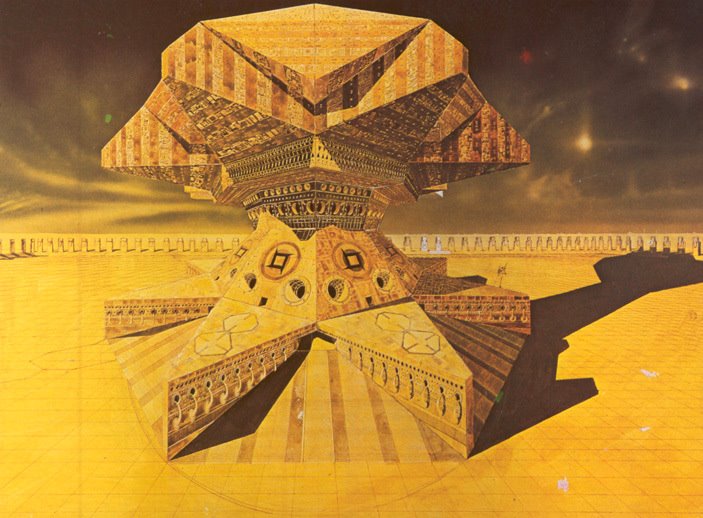

Struck by his “non-scientific” covers for sci-fi books — the antidote to the standard “gigantic freezers vomiting imperialism”, as Jodorowsky saw them — and the cinematic feel of his comic strips, Jodorowsky had Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud in his sights. In a chance meeting, he was invited to drop everything to fly to L.A. and begin work on Dune — which he did, going on to produce over 3,000 drawings. Moebius designed the characters and sets, and drew the storyboards for the film as Jodorowsky paced the room providing instruction and inspiration. When the former was ready to design the Baron’s costumes, the latter covered his own eyes, picked a book — by chance, about Titian — off the shelf, slammed it on the table and opened a random page: “It’s going to be like that!” It did the trick.

H.R. Giger, a Swiss painter whose catalogue had been handed to

Jodorowsky by Dalí, designed the planet of the bellicose Harkonnens using these storyboards as a starting point. The “dark, sick, suicidal” world of these paintings is immediately recognisable to anyone who’s seen Alien. British sci-fi illustrator Chris Foss, conversely, joined the team in Paris to provide vast, vivid spacecraft that drew on everything from Aztec architecture to tropical fish: living, breathing machines. Finally, Jodorowsky turned down Hollywood’s special effects don, Douglas Trumbull (responsible for 2001…) in favour of Dan O’Bannon, who’d co-created the no-budget Dark Star with John Carpenter. Being praised by Jodorowsky for being “completely out of conventional reality” was perhaps always a bad omen, and the experience of working for six months in Paris on a project that never came into fruition appeared to take its toll on O’Bannon. He returned home broke and spent time in a psychiatric hospital. But he kept on bashing out scripts, the 13th of which was partly inspired by working with Giger, Foss and Moebius; it would soon become Alien.

As Moebius sees it, “The film remains what it should be, a mirage between the dunes.” Some of his, Foss and Giger’s work can currently be seen in an inspired — and free — little exhibition running until October 25 at <a href="http://www.drawingroom.org.uk/intro.htm"

target="out">The Drawing Room gallery in London. Intermittently as impressive are the accompanying new pieces from younger artists, all inspired by the Dune myth. Matthew Day Jackson’s to infinity. . . presents a life-size golden skeleton with a black plastic skull dotted with abalone shell. A series of skulls alongside steadily mutate through geometric stages into a pyramid, drawing on Dune’s astral travel/cosmic consciousness themes.

Vidya Gastaldon’s superb pencil and paint drawings, each illustrating a quote from Herbert’s novel, pack a different kind of power. Bringing to mind in places William Blake (You should never be in the company…’s billowing flame and underground sandworm) or Jodorowsky himself (the eyeballs on grass-like stalks in What senses do we lack . . . recall a memorable Holy Mountain image), they nevertheless have a vitality all their own. In short, the idea of Dune still provides fertile ground for the right imagination.

Since Dune, Jodorowsky has continued to live in Paris and work at his customary, inspiring pace, but his cinematic fortunes have been mixed. At the end of the 70s he headed to India to make the children’s film Tusk, another troubled project, which he later disowned (understandably — it’s pretty bad). But in 1989 he revisited Mexico City to make his strongest film to date. Santa Sangre, funded by Dario Argento, might be described as a surreal, oedipal slasher pic with serious emotional clout. It’s one of the purest expressions of an artist’s strange soul ever committed to celluloid. With all the visual flair of The Holy Mountain but none of the esoteric excesses, everything feels just right; there’s not a second you’d cut given the option.

Following its generally positive reception, Jodorowsky was commissioned to make what’s turned out to be his final film to date: 1990’s The Rainbow Thief, starring Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif. It’s a peculiar proposition: the work of a wealthy Jodorowsky fan who hired the man himself to direct on the condition that he had no creative input whatsoever. There’s plenty to recommend it, but despite his presence on the set, you couldn’t really call it a Jodorowsky film.

So he’s busied himself by writing numerous books, comics and plays, reading, researching and restoring the Tarot De Marseilles, practising his one-man school of therapeutic work (‘Psychomagic’), donning The Holy Mountain Master’s costume to officiate at Marilyn Manson and Dita Von Teese’s wedding, and delivering ‘good news’ stories on Spanish TV news bulletins. There was talk around the turn of the millennium of Son Of El Topo — renamed Son Of El Toro and then Abel Cain in response to sabre-rattling by Allen Klein — becoming his next film, but it seems the money could not be raised. Recently, though, cinema seems to have tentatively tipped a wide-brimmed hat back in Jodorowsky’s direction. In 2004, Klein called a truce that would allow those key Jodorowsky films to be screened and lead to a superb remaster and DVD release. Even more encouragingly, shooting is apparently due to begin in Spain this month for King Shot — a “metaphysical spaghetti western” starring some or all of the following: Marilyn Manson (as a 300-year-old, flesh-eating pope who also appears as a beautiful woman), Nick Nolte, Asia Argento, Mickey Rourke, Udo Kier and Arielle Dombasle.

From what we can gather, it’s set in a casino in the middle of a desert where gangsters gamble, and where scientists begin to uncover a trail of giant, prehistoric bones that form the skeleton of a man as big as King Kong. And the story, it seems, is told by a beetle, who a prophet emerges from underground to eat. Some leaked sketches for set and costume designs look every bit as spectacular as you’d hope: the King Shot casino, topped by a huge revolver and flanked by winged sphinxes; a giant skeleton hand and Jesus-like head being excavated in the desert; a gnarly-faced pope either bellowing at or about to eat rats as big as cats. The project has backing from David Lynch, and funding apparently in place from Hungarian and Italian interests. Deceptively for a director of such lavish-looking films, Jodorowsky has always managed to shoot cheaply (Santa Sangre, he says, cost just $800,000 to make) so the signs are promising. Let’s hope this one ends up as more than a mirage.

To see our gallery of great films that never were click on the picture below