Formal training is not essential — but it sure helps!

I’ve been making art and I’ve been creating things since my memory serves me — I think it was one of the things growing up that I knew that I wanted to do, although It was more of a dream than anything else to be able to do it full time. I started out at art school, I went to the Rhode Island school of design, but dropped out after about 2 years for personal reasons. I think at that point I was kind of blown out on making art work for a number of reasons and I took a few years off of making anything creative at all. Then, when I started playing music with Baroness it very obviously opened up a door for me to start making art again, and at that point through to today I’ve really considered the band as an extension of my art.

You don’t even have to be that interested in ‘art’ to get into illustration.

I think the further back I go the more standard my influences were. Prior to going to art school I had a relatively limited knowledge of art – it was mostly the heavy hitters that I knew of, the rock stars of the game, the classical master artists — I had no formal interest what so ever in illustration. I was hugely influenced by heavy metal album covers though; a lot of Metallica, Judas Priest, Iron Maiden and Motorhead album covers — those were sort of a passing interest and certainly something that I was in awe of as a child. But I didn’t really equate illustration and fine art, I though there was really no middle grown and that was something that I struggled with for a long time before it sort of synced up that I could maybe create illustration with the fervour and zeal, and the analytic mind of a fine artist. Not to be to pretentious but I think to term yourself as an illustrator connotes that you’re constantly working for somebody else, to meet somebody else’s end, and I’ve always tried to fight that tooth and nail and really embody the work with something personal and something that’s a bit more inline with the fine artists mindset.

It’s important to develop a style, but it doesn’t happen over night.

It’s the end result of years and years of doodling in school text books and binders, and on walls! I’d just draw on anything I could. There are hundreds and thousands of little scribbles out there that when seen and looked at in retrospect were a refinement of the classical development that I when through growing up, where I just copied things and tried to imitate styles. Growing up in the 80s and 90s I went through a huge comic book phase, I went through huge phase of considering myself something of a conceptual artist, basically the entire gamut of areas, and through that investigation I was really able to develop something unintentionally that now just happens naturally. I can’t really fight it.

My work is not necessarily influenced by Art Deco, as some people think.

If anything it is more the result of an unhealthy obsession with X-Men comics! The Art Deco style was something that, I think, I stumbled across on tour at an exhibition. I saw in that style of artwork something that was reminiscent of something nostalgic from my childhood – I recognised something in it that had comparisons to a lot of artwork that I’d seen on album covers by the likes of Roger Dean and some of the other guys that had been hugely influential to me as album cover artists, so it was kind of a no-brainer to me. I find that [with the Art Deco style] there is a language there, a sort of pre existing vocabulary that I can speak in — it’s something that I’m comfortable working within and I’m able to use some of the more traditional devices to say something that’s a little more contemporary and a little more personal to me. It’s not that I’m copying them, I like to think that it’s more that I’m working within it and using it to subvert some of the standard mechanisms.

It’s important to develop a definite symbology in illustration.

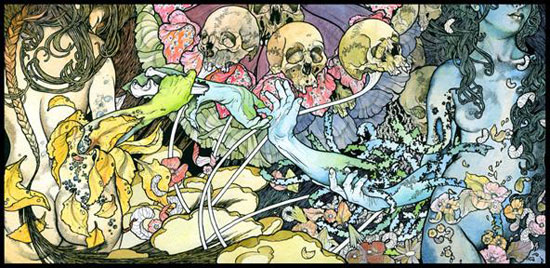

For me there is a definite symbology that I’ve been developing for years and years — decades even — at this point. Some of it I consider slightly more subconscious and some of it definitely more thought out. I like to speak, visually, in terms of metaphors and in terms of icons and symbols and avatars, and I think that some of that recurring stuff is more for me to develop a narrative. That said, I definitely spend more time considering which symbols go where and which images get repeated — how often and when — than I spend executing the rendering. There is a sort of heavy handedness to using the female form, and a heavy handedness to using some of the skeletal stuff and there’s a definite familiarity with a lot of the organic plant life and that, on a surface level, is just my way of relating to a number of different traditions — that of the punk rock, heavy metal symbology — and also to something that extends back in time and has to do with more traditional art, than music. You would certainly have no problems looking back into the annals of art history and finding those same symbols and same themes and forms repeated over and over, and that’s just because I think it’s a simple, recognisable and accessible language for the viewer to understand.

It is obvious to say it, but starting a piece is always the hardest part.

It’s about finding a balance. On one hand it would be presumptuous of me to try to start something blankly and from nothing. I like to think that I’m doing something that at least has meaning for me and, in a perfect word, is something that someone else cares about too. To that end there has to be a little pre-thought in terms of theme and concept. Conversely I think it’s equally presumptuous of me to try to see everything before hand, because I’m absolutely horrible at making scenes. I try to just work and hopefully get to a point where I know what I’m doing. Striking that balance between a critical mind and a spontaneous hand is of the utmost importance to somebody like me who works in a medium that is so exacting, and so detailed and precise, and so permanent.

Leave room for, and embrace your mistakes.

To call them mistakes may be a bit of a semantic mistake — I don’t consider them mistakes, they’re more ‘technical errors’, they’re more ‘missteps in draughtsmanship’. To use a musical analogy: if you go back and listen to certain pieces of music which are widely considered absolutely quintessential classics, something like Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew, something like Led Zeppelin IV, these archetypes of great music, of great art, it’s through those mistakes and through those little missteps in techniques that I think you can see the personality of the creator. I’ve never had the mindset that I have to make something technically perfect because I think that if my draughtsmanship was absolutely pinpoint accurate, then ultimately the piece I’m creating is lifeless — there’s no room for improvement. I’m a staunch disciple of the ‘process’ of making art, it’s a life long thing where you learn more from your missteps and you’re errors than you do from your accolades and perfection. I try to leave room for mistakes and risks to happen, because otherwise, I’m just rendering something. I don’t consider myself adept at rendering, I think it’s a by-product of the reactive or intuitive process.

Choose your commissions wisely.

It’s a sum total of a number of different factors. For me, most immediately, I have to actually like the music of the band that is approaching me, that’s quintessentially important. I won’t do something for somebody — a band or a musician — who I don’t respect, admire, look up to or just have a gut level friendship with — I consider myself fortunate because I’ve gotten to work with all of those people. I’ve gotten to work with friends of mine, I’ve gotten to work with heroes of mine and I’ve gotten to work with a tonne of bands who I just plain respect. That’s not to say that I have a ‘buddy system’ where I’ll only work with friends but within my group of friends there’s an incredible talent pool and there’s some very creative and very forward-thinking musicians and artists that I’ve been fortunate to become friends with and have gotten to work and collaborate with.

Be sure to take breaks. You can’t do everything, all of the time.

I actually barely make any art work when we’re on tour. The way we tour, and the place that I get to — that I reach into mentally — doesn’t allow for much back and forth. On the road it’s a fairly intense manner of living, it’s an odd profession and it drains me. I’ve tried at times to be creative both musically and visually when I’m on tour and it negatively effect’s both avenues. When I’m at home I’m able to strike that balance a lot more easily but when we’re on tour for example, I drive the van most of the time and suffice to say that the performance is physically draining — there’s a mental, physical and spiritual drain that any touring musician will tell you about — that sort of prevents me from making too much art work. Honestly though, there are times when I’m making art and I just want to be on tour and then there are plenty of times when I’m on tour when I wish I was just at home in my studio making art, you just have to split the difference between the to. Making art is such a hermetic thing, it involves no one else — it’s a complete insider thing — and then performing music demands an audience. So there’s such a different out look, right from the get go. But it’s nice, when I get blown out on dealing with people all the time — and I’m a fairly anxious person — I always have art work to look forward to, it doesn’t require any speech or socialising, or anything like that.

View some of John Baizley’s work here.

Baroness’ Blue Record is out soon on Relapse