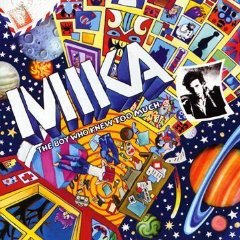

As fans of The Horrors, Bat For Lashes, Simian Mobile Disco and numerous others will tell you, this has been a banner year for Difficult Second Albums — although it’d be fair to say that the majority of the artists in question have had a somewhat easier task ahead of them than Mika. After all, his nearest peers from this decade, The Darkness and Scissor Sisters, stumbled rather horrifically at the same stage, to put it mildly. His debut drew absolutely nothing but bouquets and brickbats to a degree barely seen since, ooh, Moseley Shoals, probably; and his entire raison d’etre from the outset has been to be as properly famous as his obvious idols — clearly, acclaimed obscurity simply will not do. So, you know, no pressure. . . .

With this in mind, it’s interesting that lead-off track ‘We Are Golden’ presents his challenge in microcosm. It’s a fearlessly gigantic pop statement, of course, and an almost suicidally gymnastic showcase for his remarkable vocal range. But it risks leaping a trifle too hard on the kitsch pedal by introducing a children’s choir; it tends towards being far too mannered for its own good; and its “c’mon-everybody” communality really only works if you’ve already been prepared to buy into Mika as a shamanic figure — which will make it four minutes of naught but blackboards and nails to his detractors. Previous problems rear their head elsewhere, too: at its worst, Life In Cartoon Motion suggested that its maker had clocked the combination of narcissism and neediness in Robbie Williams as the thing that the public warmed to, and this criticism looms large over ‘Blame It On The Girls’ (whose I’m-so-ugly sentiments sit uncomfortably with his present popstar-in-his-pants exhibitionism). Meanwhile, ‘Dr John’ not only sounds like the work of someone who’s never heard of the New Orleans Night Tripper, but also contains trumpet so redolent of low-rent 1970s light entertainment that we find ourselves hoping the ghost of Ronnie Hazlehurst will embark upon an apoplectic stage invasion.

Mind you, it’s curious how convincingly someone in their mid-20s has conjured up the dying days of the decade before they were conceived; on that level, there’s something to be admired here. ‘I See You’, for instance, works both because its piano-chasissed pathos steers near Elton at his peak and because of its uncharacteristic restraint, a quality that future recordings would undoubtedly benefit from. And ‘By The Time’ takes its languorous cues from Wings’ ‘Let ‘Em In’ — not their finest hour by any means, but one that lends itself to this appropriation satsifyingly enough. He’s also remembered that ‘Relax’ stood out so on his debut partly due to its from-out-of-nowhere quality, and makes two somewhat successful stabs at the same trick here. ‘Toy Boy’ is an unexpectedly cute cabaret fantasia that nonetheless sits rather in the shadow of the Dresden Dolls’ ostensibly similar (but, inevitably, much more salacious) ‘Coin Operated Boy’; but he hits paydirt with ‘Rain’, which lurches incongruously from his favoured oeuvres — and indeed eras — drawing sustenance from the unlikely 1996-centric double whammy of ‘Your Woman’ and ‘Seven Days And One Week’. It also throws in a talky bit that’s part-Tennant and part-Lowe, with amazingly joyful consequences. Really, more of that’d be marvellous.

What we get instead, alas, is an all-too-frequent anonymity totally at odds with this record’s regular, overly-orchestrated bursts of LOOK-AT-HOW-TECHNICOLOR-I-AM! Plus, while his lyrical tics are more conciliatory than before, some of the singing here borders on the disastrous — his medium register goes balloonishly squeaky in ‘Pick Up Off The Floor’, and the pronunciation hoops he sometimes puts himself through (getting ‘April’ to rhyme with ‘hateful’ in ‘Good Gone Girl’ is the main offender here, though hardly an isolated one) are needlessly complex. What saddens the most, though, is that he currently finds himself so comprehensively outclassed in every area that ought to be one of his assets. Falsetto filth? You’d be better off with Two Dancers. Cerebral theatrics? Far more imaginatively pursued on Grammatics. Tightrope-traversingly cosmic colossalness? Why, step right up to The Resistance. Unlikely to seduce the sceptical, and too equivocal for the evangelists, The Boy Who Knew Too Much is ultimately nowhere near as smart as it’d like to be.