Reading fellow Quietus scribe Neil Kulkarni’s harsh-but-fair-but-ultimately- wrong review of the Stone Roses’ re-released debut LP the other day was, for me, a complicated experience. For while I find myself agreeing with many of his points, I come to an entirely different conclusion.

This is an LP that drags such social contextual baggage along with it that it is indeed hard to separate it from, as Kulkarni eloquently puts it, the “sideyed-up desert-booted monkey-strutting wankers” for whom it is such a touchstone. However, he makes the same mistake as those very wankers* in seeing the album’s release as the moment “when Year Zero for lad-rock got declared”. There has always been, to me, a strange dissonance between what the Roses actually were and what they appeared to be, to both fans and detractors. Indeed, I’ve often felt that were the Roses less widely misunderstood, those two groups would more or less entirely switch sides.

One wonders what the lads who erroneously idolise Ian Brown as the master-blagger cheeky scally could possibly make of the Brown who, like guitarist John Squire, was an earnest member of the Socialist Workers Party, teetotaler and attentive reader of Guy Debord. What can they make of the Mani who first met Squire and Brown via an ad hoc network of early 80s Manchester scooter gangs getting together to picket National Front demonstrations? What do Squire’s action paintings, sculptures and collages mean to them? And what on earth do they even like about the blend of aching vulnerability and socialist revolutionary ire that is shot through everything the Roses did in their halcyon period from late 1987 to summer 1990?

It’s always reassured me that the bookish and politically hard left Manic Street Preachers and the flamboyantly androgynous Suede – two of the smartest and least laddish bands in British music history – were Stone Roses fans. When I listen to the Roses, I can’t even begin to connect their fluid sensuality, emotional unselfconsciousness and sophisticated socialism with the bands that came in their wake; least of all the uptight, fists-up-Mother-Brown terrace singalong dullardry of Oasis, the band who most regularly cite them as an influence. There is an anthropology PhD waiting to be written about how Noel Gallagher managed to listen to an LP as conceptually complex and painfully tender as The Stone Roses as obsessively as he claims, and then write something as ham-fisted as Definitely Maybe.

Of course, it’s equally hard to connect the latter day bible-thumping stoner Ian Brown with his far sharper and more interesting younger self, but that’s outside the scope of this article, and possibly beyond the wit of man to fathom. But no matter: what we’re discussing here is the Roses and what they meant back in the day, not whatever fresh hell has made searching for them on Spotify bring up a terrifyingly bad compilation called One For The Lad’s [sic].

There’s a deep irony in the fact that Liam Gallagher marks the moment he decided to be in a band as the Roses’ tipping-point performance – an immediately pre-fame anti-Clause 28 fundraiser gig (for the youngsters: Clause 28 was the Conservative Thatcher government’s overt attempt to make gays as culturally invisible as possible).

This is not to suggest Liam is a homophobe, by the way; I am aware of no suggestion that he is (and also aware that Brown, despite attending that gig’s related march with Squire and drummer Reni, may well have become so in the intervening years, judging by some dodgy statements in the late 90s). It’s more to point out that while the Roses cast a long shadow over the hedonistic 90s, they were – all in their late 20s by the time this album was released – more a product of the spartan and politically embattled 80s.

Growing up in the north during the Thatcher government’s miner-crushing, at-war-with-Liverpool-Council imperial phase was both a politicising and politically polarising experience. Brown was, at the time, wisely dismissive of the economic “north-south divide” cliché, rightly pointing out in a radio interview that there was “poverty in London that’ll make your eyes bleed”, but the mid-to- late 80s were, nonetheless, a time when the major cities of the north of England – Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield, Liverpool – were hugely disconnected from both the central government and the popular media.

The negative aspects of this are both obvious and well documented, but the huge positive was that these cities and the towns surrounding them – studded along a strip of motorway that later became the superhighway of the northern rave scene – were free to create and assert their own popular culture and political sensibilities.

The Roses, easy to dismiss at a glance as inward-looking 60s classicists, were right at heart of this activity. There was a thriving warehouse party scene in the UK long before anyone called them “raves”, and in the Manchester area in particular these parties were incredibly musically diverse, including 80s indie, punk, goth, new wave, northern soul, hip hop, and the first steps out of the closet of two previously punk-banished strands: shameless disco-pop in the emerging form of house music, and the retro psychedelic delights of Jimi Hendrix and Sly and the Family Stone.

Never especially keen on the standard gig format, the Stone Roses organised and headlined a number of these parties in the mid-to-late 80s. And while many critics have used their peers Happy Mondays as a stick to beat them with – unfavourably comparing the Byrds-isms of the Roses’ debut with the broad church of any given Mondays LP – a closer look shows both bands drank from the same musical reservoir, and were equally, restlessly on the move.

For kids who grew up on punk, the 60s weren’t the cultural comfort blanket they are now; this was the forbidden zone, flirting with the loathed culture of the hippies. But as Brown later said to Q magazine: “Punk stopped you listening to stuff like Hendrix and then years later you hear Electric Ladyland and it’s an excellent LP. But at the time you don’t listen to it because you believe all the bollocks. I wish I’d heard Jimi Hendrix when I was 12.”

The Stone Roses’ oft-vaunted – by the press, not the band, note – link to house music is, let’s face it, musically non-existent. Never mind the LP, even ‘Fool’s Gold’, their most danceable record by far, is a mish-mash of hip hop (the bassline and guitar licks are note-for-note stolen from ‘Know How’ by Young MC) and krautrock (the rolling rhythmic feel and sinister lyrical obliqueness is directly cribbed from ‘Vitamin C’ by Can). And if that’s not eclectic enough for you to admit we’re not talking about the bloody Bluetones here, I’d venture you’re being a bit churlish.

Musically, the Roses tended to run through distinct phases, which they would explore thoroughly before moving on. They were already done and dusted with their punk and vaguely Smiths-y periods by mid-1988. The debut LP simply catches a snapshot of where they were right at that moment, which was a sort of mod-psychedelic, Sly-tinged power pop.

Which brings us, at last, to the album itself. Here, I should declare an interest. As a teenager, I think I listened to this LP at least once a day for a couple of years, so of course I am somewhat fond of it.

On the other hand, listening to this re-release, I find that of the three CDs and sundry bits of vinyl, “the greatest album of all time” is the part of the package that time has been the least kind to. There’s a stoned, glassy-eyed sheen to the production that has dated terribly, and – in tune with the bands’ own oft-stated objections – actively undercuts their best qualities (Reni and Mani’s Siamese- twins rhythm section, Squire’s gift for guitar tone as opposed to flash) and emphasises their worst (an ungainly folksiness to some of the vocal harmonising, a slight fussiness to some of the arrangements).

Indeed, this re-release’s saving grace is the second disc showcase of the many glorious B-sides they released through 1988 and ’89. John Leckie’s production of these tracks is less prissy and reverb-drenched, and the band’s drive and authority comes through on songs like ‘Mersey Paradise’ and ‘Standing Here’, probably the best studio captures of their crystalline yet hard-edged live sound, and both better songs than a good half of the LP.

Nonetheless, I can’t agree with Kulkarni’s assessment that the LP falls to bits after the first three songs. My take on this record has never been that it’s the best (far from it), rather that it’s one of the most complete British rock LPs. It’s so stylistically coherent, such a closed system, and so perfectly paced and sequenced, that – like eating ice cream – the only thing that quite fits the bill afterwards is… the same thing again.

Recorded at the exact moment the leftfield culture of warehouse parties and political dissent was being transformed/augmented/co-opted (delete according to disposition) into ecstasy-fuelled rave culture, and the first falterings of Thatcherism’s previously iron grip were becoming apparent, it felt, as a friend memorably described it, “like listening to the news”. The hazy, valedictory dreamscape the record conjures up is, of course, a misleading fantasy, as was the whole ecstasy-drenched moment. But who cares; it was a glorious delusion.

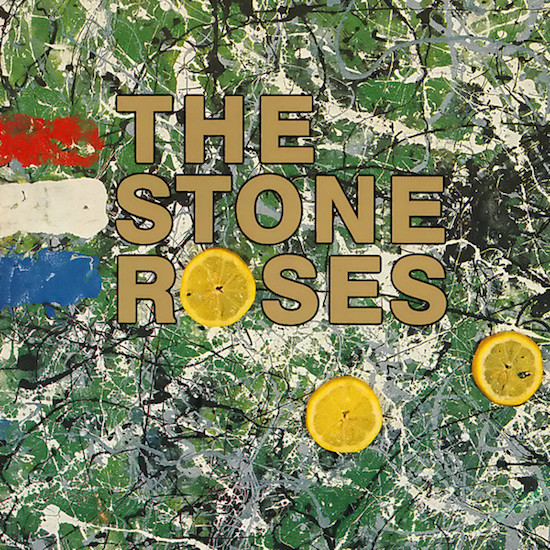

The case against all this contextualising, of course, is that it’s hard to glean any of this simply from listening to the LP in isolation. If you’re aware, for example that Brown wrote the lyrics to ‘Bye Bye Badman’ from the point of view of a Paris ’68 rioter, that the line “citrus sucking sunshine” refers to the rioters using lemons as a crude antidote to police tear-gas, and that the album’s cover image of lemon slices, chaotic Jackson Pollock swirl and a crudely daubed French tricolor is an abstract visualisation of the same, then there’s food for thought. But if you didn’t happen to read that particular interview, there’s probably zero chance of you figuring it out. A certain obliqueness is often central to a band’s appeal, of course, and that’s certainly true here. But in fairness to the Roses’ detractors, it’s extremely easy to hear the same song and see the same cover image and pick up nothing more than a general neo-psychedelic wooziness that sounds great when you’re on drugs but isn’t necessarily of any particular substance.

It’s for someone younger than either Kulkarni or myself to say what it’s like to come to this LP for the first time in 2009, but I know what it felt like in 1989, and if you told me it would spawn the hideous early 90s baggy bands, right through to graceless tosh like the Twang and the Enemy, I’d have laughed my head off. More fool me. Still, as Kulkarni says, “There’s a lot you can blame the Roses for, most of it not their fault.”

The Roses themselves have consistently hovered between being amused and downright derisive about claims that it is “the greatest album of all time”. Ian Brown, speaking to the Guardian in 2004, had this to say: “We went in wanting to make a record as good as Electric Ladyland or Never Mind The Bollocks… We were a little disappointed though, and the last 20 seconds of ‘Don’t Stop’ is the only bit of the record we all got really excited about, because we thought it sounded so different… I’m proud of it, but it’s not close to Hendrix, The Beatles or Stevie Wonder. I haven’t listened to it for a long time.”

Me neither. But I’ve enjoyed it tonight for sure.

*Neil is not a wanker, of course. He’s a fine gentleman who just happens to be wrong about this record.