“I have a wonderful life. I do pretty much what I want, and the only real problem I ever have is wondering what that is.” (Brian Eno, A Year with Swollen Appendices.)

It’s an ambitious, some might say foolhardy, enterprise to write a comprehensive account of the life and work of Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno. If the simple abundance of the man’s names doesn’t deter would-be biographers, then the task of engaging with his work’s sheer diversity probably will. While it’s a complex enough proposition even to say what his work is, the ongoing proliferation of Eno’s areas of interest and activity has only made the job progressively harder; over the years it’s become more and more of a challenge to paint a coherent picture of what he does, never mind to assess how successfully he does it, and this no doubt explains why no one has managed.

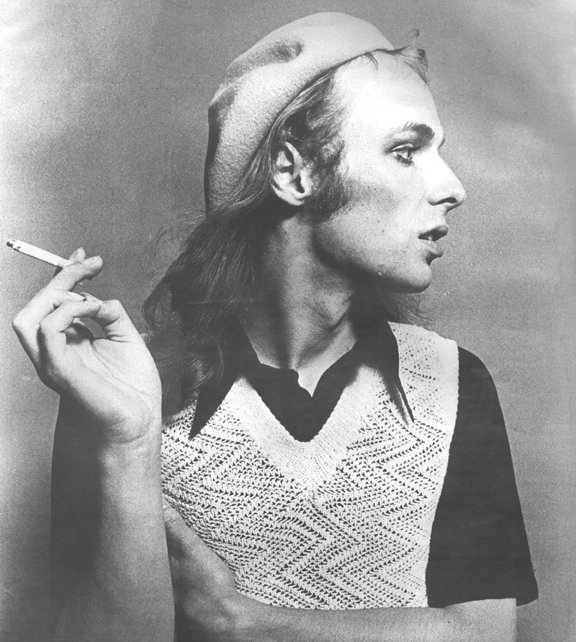

David Sheppard makes a laudable attempt with On Some Faraway Beach. Drawing on his own interviews with Eno and a cast of associates including Bryan Ferry, John Cale, Robert Wyatt and David Byrne (plus a wealth of secondary material already familiar to Eno-spotters), Sheppard tracks Eno’s iterations: from solitary, fossil-collecting, hymn-loving child to balding, lascivious Roxy musician to Oblique Strategist to ambient pioneer to mega-producer to Lib Dem youth adviser, and all points in between. Focused primarily on his subject’s music, this weighty tome takes Eno’s mountainous CV by strategy, the strategy being to identify and follow the aesthetic thread running throughout his heterogeneous work: that unifying motif is Eno’s valorisation of process over product and his emphasis on a systems-oriented approach, encapsulated in the Cageian mantra, “Define parameters, set it off, see what happens.”

Sheppard doesn’t merely recount his subject’s origins by way of background information, serving only as a de rigueur point of departure. Rather, he insightfully suggests ways in which Eno’s artistic practices and the richly varied creative places he’s visited over the course of his career are inextricably linked to formative experiences and, moreover, to the very particular context of those experiences.

Whereas in 1972 speculation had it that Eno came from another planet, he actually hailed from down-to-earth rural Suffolk, but as Sheppard shows, there was more to the small town of Woodbridge than met the eye. The location of Eno’s prosaic upbringing positioned him ideally for a series of encounters that would mould his sensibility. Historically, geographically and culturally, Eno grew up on various “cusps” as Sheppard describes it, tracing lines of continuity between an early sense of in between-ness and Eno’s famously polymorphous personality. For Sheppard, this cusp experience predisposed him to seeking out and traversing different traditions, disciplines and media, all the while cross-pollinating, juxtaposing and hybridising elements gleaned from those encounters – and always with a disregard for conventional, hierarchical distinctions between high and low culture.

Eno was born into a time of postwar transition, coming of age in the mid-’60s amid radical changes in Britain’s socio-cultural and political identity. Although Woodbridge, with origins in the Middle Ages, was a seeming bastion of good old-fashioned Englishness, in the late ’50s that tradition rubbed up against its other: American pop culture. The presence of American air bases and 17,000 US servicemen in the surrounding area made Woodbridge an improbably happening place, an environment in which a young Eno was exposed to the then-exotic sounds of rock’n’roll and doo-wop, thanks to Forces Radio and jukeboxes in the town’s cafes, filled with the latest 45s to satisfy the GIs. Hearing ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ for the first time made a profound impression on Eno, as it did on a generation of future musicians. Eno, though, was struck by a specific aspect of the recording: its foregrounding of studio artifice, underlined by the unique, tape delay-crafted texture of Presley’s voice – this early example of the studio’s potential as a place to create music rather than just document a performance would find resonance in Eno’s subsequent working methods.

Exterior forces notwithstanding, some of Eno’s initial acquaintance with otherness came from within his family, which boasted a lineage of musicians and oddballs who shaped his world view. None more so than the eccentric, well-travelled Uncle Carl, who nourished a spirit of eclectic inquisitiveness in his nephew with his houseful of books, artefacts and bric-à-brac from around the globe — from suits of armour and swords to illustrated monographs on Mondrian.

Eno’s foundation course at Ipswich Civic College furnished him with a singular arena in which to find a medium and develop an approach to it. Key in that regard was radical head tutor and cybernetician Roy Ascott, whose slightly unhinged regimen was geared towards having new students unlearn everything they knew about making art. (Ascott also played pupils the Who’s ‘My Generation’, in the process providing Eno with a Damascene moment about the possibilities of marrying art with pop music.) Instead of working towards the production of finished objects, the students engaged in ludic group exercises that were aimed at fomenting counterintuitive thinking, cooperative strategies and generative systems, as well as dismantling hierarchies and eschewing virtuosity in any particular medium. Another tutor, Tom Phillips, gave Eno something more concrete to hold onto by introducing him to Cage’s experimental propositions in Silence – a conceptual primer for the avant-garde that advocated the rich potential of sound (musical and non-musical) and championed indeterminate, aleatory processes over traditional composition and performance. Phillips also counter-balanced some of Ascott’s more anarchic tendencies by instilling in Eno the importance of bringing discipline and rigour to bear on his work. Consequently, at Ipswich Eno began formulating what would be his own core aesthetic principles as a (non) musician, as a visual artist and as a producer: a focus on process, creative problem-solving and an interest in art generated by systems.

In addition to exposing Eno to American composers like Cage, Morton Feldman, La Monte Young and Christian Wolff, Phillips introduced him to the English avant-garde scene; encounters with the likes of Cornelius Cardew, Howard Skempton, John Tilbury, Gavin Bryars and Michael Nyman prompted Eno’s realisation that, while not a musician, he could use sound as his raw material. Things further coalesced when he read about Steve Reich’s tape recorder compositions, which offered striking examples of sound being manipulated to make “sound paintings.” To Eno this was a perfect example of an art form constructed around systems and processes; he embarked on his own primitive explorations with the college’s two reel-to-reel machines. Sheppard’s account of Eno’s gravitation towards figures such as Cardew and experimental music circles (leading to his involvement in Scratch Orchestra projects and, later, the Portsmouth Sinfonia) makes the case that Eno was part of the late-’60s British avant-garde. His unique contribution to that tradition was his eventual crossover from the high-culture realm into the realm of pop, not so much mixing the two as refusing to accept the distinction between them. Eno was one of the first, and remains one of the few, British musicians to come at pop music from the conceptual perspective of fine art.

Owing to Eno’s myriad sites of activity, Sheppard characterises him as a Renaissance man. That’s not entirely apposite: such a designation presupposes expertise and virtuosity in multiple fields, something Eno lacks and has consistently made a virtue of lacking. Moreover, that metaphor doesn’t quite get at the notion that Eno’s discrete endeavours in each of those manifold areas are not the primary source of his significance; more accurately, his significance lies in the way he combines them as ingredients in a collage. Whether he’s working with people, concepts, media or sounds, Eno’s forte resides in bringing the components together and setting processes and systems in motion, with a view to triggering new narratives and meanings as a result of that amalgamation of disparate elements. This collage impulse towards juxtaposition and hybridisation is quintessentially postmodern and, in Eno’s case, it dramatises one of the perceived pitfalls of postmodernism: a privileging of surface over historical engagement and depth, a lack of attention to history.

There’s been little sustained analysis of this potential weakness in Eno’s work, as most of his critics satisfy themselves simply by labelling him a dilettante. Sheppard touches on this with reference to Jon Pareles’s 1981 Billboard review of My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, one of the few contemporaneous responses suggesting a direction that more substantive critiques might take. On that album, Eno and Byrne sought to catalyse new musical narratives with their cutting and pasting of found and sampled sounds, but Pareles saw an ethical problem in what he deemed the album’s tendency towards dehistoricisation and cultural tourism. In his opinion, the excision and appropriation of elements of African and Middle Eastern traditions from their original context via samples was an instance of orientalist fetishism that “raises stubborn questions about context, manipulation and cultural imperialism.” This connects with the views of Eno associate Russell Mills (as quoted by Sheppard) regarding Eno’s visual artworks. Mills is less engaged by the visual works because of what he considers their hermetic nature as self-contained systems principally about themselves and their own processes; Mills feels that, rather than gesture outwards or exist in relationship to history, they’re cut off from material conditions, gesturing ultimately only to themselves. Indeed, Eno himself has spoken of the function of art exactly as a kind of escapism, as a flight from reality, but one that might, in turn, inspire improvements to reality.

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts and Talking Heads’ Remain in Light were the culmination of Eno’s fascination with African percussion and African music in general, forms that – ironically – appealed to him precisely because of their dynamic, radical relationship with their site of production. What made African drumming especially attractive to Eno was that it embodied and enabled non-hierarchical structures. Western traditions of the orchestra and the ensemble reproduced rigid social hierarchies in terms of both their organisation and the way they constructed music, starting with the authority of the composer and the notated score; African music, on the other hand, excited Eno because it relied on a more democratic “network” model of collaboration and improvisation. For him, this also resonated with the lessons on process and group-play learned from Ascott; with the possibilities for indeterminate music mapped by Cage and put into practice by Cardew’s cooperative Scratch Orchestra experiments; and with the theories of organisation, management and performance developed by Anthony Stafford Beer, whose books had interested Eno since the mid-’70s. Nevertheless, despite the attractiveness of a non-hierarchical model and the displacement of the authorial figure in favour of team work and mutual participation, a clear hierarchy reconstituted itself in the case of Remain in Light as the band fractured into opposing camps and the songwriting credits identified Eno and Byrne as the record’s principle composers.

In addition to its portrayal of Eno’s creative and intellectual life before Roxy Music, On Some Faraway Beach‘s strongest segments are its coverage of his work with Talking Heads and Byrne; its dissections of his ’70s solo albums; and its discussion of the Bowie, Cluster and Robert Fripp collaborations. In fact, Sheppard devotes more than three-quarters of the book to Eno’s pre-1982 life and work, shoehorning the next 26 years into the remaining quarter (the ’90s are polished off in about 30 pages). This perhaps highlights a fundamental problem facing a biographer working on an artist with a lengthy and continuing career: that we don’t yet enjoy enough historical objectivity to evaluate fully the artist’s oeuvre, its context and its significance. However, Sheppard is clear on the reasons for the book’s biases, noting that “the last decade […] has offered little to truly match the luminous originality of [Eno’s] benchmark 1970s solo albums.”

That’s not to say that On Some Faraway Beach isn’t meticulously researched and hugely readable, balanced perfectly between contextualisation, commentary, astute analysis and fascinating anecdote. Sheppard also manages to squeeze in plenty of minutiae and amusing detail: the presence of a garden shed inside Eno’s Notting Hill studio; the fact that we have him to thank for inspiring Phil Collins to launch a solo career; eyewitness reports of Eno’s prodigious accomplishments with what Fripp once dubbed the “sword of union”; and (undocumented) claims by Eno that, in order to make ends meet, he briefly appeared in porn films.

Above all, the book skilfully blends Sheppard’s voice with the voices of his many compelling witnesses. Figures like Russell Mills and John Foxx, who have worked closely with Eno in different contexts, offer thoughtful, insightful observations. (Curiously, space is also given to less informative subjects with no first-hand working experience.) For the most part, it’s only the notion of Eno’s dilettantism that prompts less than favourable assessments by some interviewees. Even so, it’s interesting that despite suggestions that Eno and his work are all about surface and despite backhanded compliments about his ability to be persuasive on any topic, detractors don’t explain how this is the case or show they’ve explored the areas that Eno’s supposedly bullshitting about. Their criticisms also remain on the surface of things, rather than examine the conceptual framework underlying his wide-ranging work.