Gothic Rock, that most despised genre, has a new reference work, authored by long-term advocate, apostle and true believer Mick Mercer. Music To Die For is a listings-based compendium that samples the quite bewildering array of goth-related artists currently extant (and a fair few extinct) from across the globe. Rather than attempt to quantify or appraise the relative merits of the artists, it settles into a discographical telephone directory approach which is leavened by the artists’ own insights (a nice mix of bravado and modesty) and Mick’s own asides.

It can be most amusing stuff, at best. For example, we have the tell of the Psycho Surgeons, who had their leader’s ashes pressed into the vinyl of their single (after his intention to travel to the next world in a home-made coffin were rejected by the local crematorium because it represented a ‘fire risk’). Given goth’s propensity for high camp and melodrama, there an awful lot of bands prefaced by the demonstrative pronoun (This Ascension, This Burning Effigy, This Empty Flow, This Gentle Horror, This Vale of Tears). An even greater number opt for the indefinite article (A Covenant Of Thorns, A Deeper Sleep Than Death, A Dream Of Poe, A Garden Of Strange Flowers, A Hollow Grave etc). But the ones on my immediate hit list are the UK’s Barbarossa Charm Offensive, Germany’s Damage Done By Worms and Puerto Rico’s Serenity And Emptiness.

One can only gaze in wonder at the profusion of Joy Division tribute bands. Closer To Curtis (Netherlands), Exercise One (Germany), Joy De Vivre (Belgium; and surely missing the point) and the fantastically named Jah Division (Brooklyn band who play dubbed up JD songs). Although, as Quietus editor John Doran points out, they’ll have to go some to top Boy Division, the ‘male dancer’ version or Oi Vey Division, the Hasidic Jewish Curtis clones.

A few eyebrows might be raised at some of the inclusions. The Joy Division/Siouxsie ‘were they, weren’t they’ conundrum is oh so familiar. But Mercer has also included Johnny Cash, the majority of the 4AD bands, psychobilly groups and pertinent black metal acts. The resource embodies a far greater stylistic variety than the casual observer might imagine. I call upon the author to explain.

"I am sure there will be far more variety in the book overall than people may be expecting," he says, "but that’s half the point. I WANT them to appreciate this, and to revel in the peculiarities. It does all make sense. Country noir has been coming through increasingly, so they should at least appreciate the complete discography of Johnny Cash, as should anybody else. Also, it’s going to have the odder ends of post-punk, just as it will have the straightforward goth metal."

The thing that comes across most strongly is the cross-border penetration of what Mercer calls ‘the last great international underground’. Most genre histories tend to concern themselves with the UK or US. Yet the Balkans, South America and Thailand/Philippines seem to be better represented here than anyone might imagine. Both Portland, Oregon and Russia have particularly vibrant Goth subcultures, it would seem.

"I wanted it to have the widest geographical discoveries because that’s the real thrill of the chase for me," Mercer confirms. "I love the fact I can find bands throughout the world, especially countries that were pretty closed before MySpace made things so much easier, and so much more enjoyable."

The way Mercer approached cataloguing and presenting this information, as admitted in the introduction, turns on the artists’ own willingness to become involved in the process. There must have been frustrations, but equally, it’s produced some insightful and amusing anecdotes. It’s a reference work, therefore, in the purest sense, without any attempt to chisel the facts into critical theory or fit a particular line of enquiry.

"The way I did the book evolved fairly naturally," Mercer concedes, "even if haphazardly, and that is reflect in the jumbled nature. It’s as it is should be – the opposite side of the fact technology makes this possible. This book is stuffed full of the best and most artistic music the world has to offer. More bands than you can shake a stick at, which is against Healthy & Safety anyway, and it’s all there, in the depth, in the obvious, in the unlikely, in the frankly mysterious. What seems enigmatic initially can be utterly addictive. It’s what music is, but in the form of a book."

For more on Mick and goth click here.

And now from his book . . .

WE WEREN’T REALLY A GOTH BAND PER SE . . . STORIES FROM THE GOTH WARS

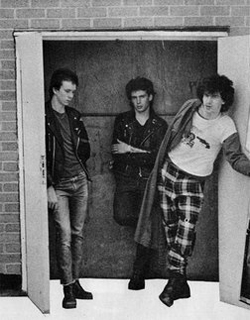

Spon, UK Decay

After joining us in February 1981 for a brief Belgian tour, Steve Keaton wrote a great feature for Sounds entitled ‘The Face of Punk Gothique’. We had a really good time together and joked about ghouls and ghosties. He seemed to be the first one to pick up on the ‘jovial darkness’ mood of the music rather than the punkier side. I think that article turned out to be not only our first major music interview, but the first signs of ‘gothic’ imagery being used in that way. At the time there was a lot a talk and an overwhelming feeling of something new happening here in the UK. We were headlining and selling out larger venues than ever before, with a new style of exciting support bands. Different labels were used to describe this emerging movement but later, for better or worse, it all seemed to get described as gothic rock.

We were conscious of retaining the integrity of our punk roots and not betraying the principles that came from the initial wave of punk. Over time we gained confidence and started to throw deeper, darker and more meaningful messages into the mix. We didn’t deliberately set out to write ghastly or ghoulish songs , we wrote of things that would fascinate or move us. The band was fortunate enough not to have to suffer the pigeonholing that the term goth would bring to many, for it didn’t become ‘in vogue’ until after we had split.

By 1982, most of the leading post-punk bands, one way or another, had left the arena for fame and fortune. We found ourselves gaining a new momentum in the remaining underground movement. With a new class of bands following on such as Play Dead, Dance Society, Sex Gang Children, Southern Death Cult, Sisters of Mercy etc, there was a very real sense that something special was happening. Yes, I do think we helped wedge the door open a little for the coming of this new sound and attitude. At the time, it was nameless, fresh and uncorrupted. Later, well that’s history, humanity and ‘goth’.

Ian Astbury, Southern Death Cult/The Cult

It was (NME writer) David Dorrell, later manager of Bush, who was the instigator [of the term goth]. It came from Andi of Sex Gang Children. He lived in this Victorian apartment block in Brixton. We referred to him as Count Visigoth and his followers, the gothic hordes. And Dave Dorrell was around Brixton at the time, and it kind of became a joke. Just sort of teasing Andi, because he had the curtains drawn all the time and was always wearing a Chinese robe. At that time you would see girls with teased black hair, occasionally you’d see a girl wearing bat earrings or something, principally followers of Siouxsie And The Banshees, and that’s what it derived from. And then I think David wrote an article referring to ‘goth’ in that way. That was pretty much it. Anything that looked dark with spiky hair was called goth. In America it was referred to as death rock. goth is a crap word! I like ‘death rock’ better – much more romantic.

We were like the younger brothers of the punk bands, by about five or six years. Which is quite a huge gap in terms of age difference. They were in their early 20s and we were in our young teens, 13 to 15. The punk shows, the Pistols, the Clash, the Banshees, whatever – we were in the audience. And we picked up the instruments because of the Pistols and those bands. Our lineage and heritage goes back to those shows. I first saw the Clash in ’78 in Glasgow, the Stranglers and the Damned and Ramones, I was at those shows. For me, it was such a spectacle, especially being in Glasgow at the time, it was so exotic, it was mind-blowing. It was transcendental. It still stays with me. They are the most amazing performances I’ve ever seen, or probably will ever see.

There were other influences coming in. Joy Division were incredibly important. Ian Curtis was such an icon for us, for me anyway. If you listen to bands in the early 80s, a lot of singers were going for that kind of baritone Jim Morrison/Ian Curtis vocal style. Echo and the Bunnymen definitely. There was a lot more in common with that. And then the energy of punk rock fused with that. I used to wear World’s End [gear]. I was more into the tribal end of goth. I was into American Indian imagery. There was a whole sect of kids who were into World’s End. They were Southern Death Cult fans cos we were into the tribal imagery and everything. Then there was Adam And The Ants. Dirk Wears White Sox has as much to do with Goth as Siouxsie And The Banshees.

Pete Murphy, Bauhaus (in an interview with Suzan Colon)

I know that Bauhaus presumably started what the critics coined the ‘gothic’ genre in 1979 with ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’. But goth was a myth dreamt up by journalists sometime back in the 80s to describe Bauhaus, Joy Division, Iggy’s vocal vibe on The Idiot, and so on. The music was often unaccomplished, but made up for it with a kind of transcendent quality.

Mrs Fiend, Alien Sex Fiend

When we started in 1982, there was no such term as ‘goth’ or ‘gothic’; 25 years later it’s a whole different story! Initially we were called a ‘Batcave’ band, obviously because we did our very first gig at the Batcave club (in Soho, London) and later on did the Batcave tour, etc. We’ve been asked many times when the term ‘gothic’ started being used – but we really can’t remember! It’s a topic that comes up all the time in interviews. We’ve even recently taken part in a radio debate about what is and isn’t goth and the conclusion reached was that no two people can agree about it! It got so bizarre and anal that when Nik was asked what the ‘true spirit of goth’ was, he said Jack Daniel’s! That sense of humour/irony and some of our theatricality is why some people don’t see us a goth band, whereas other people do!

Nik Fiend, Alien Sex Fiend

To me, the real world is a lot more gloomy than goth! Real life is way more scary. For me the whole thing is about escapism and freedom to express yourself. Early on the term ‘goth/gothic’ was usually used as a derogatory term by the media. We got terrible reviews like ‘the ugliest thing in the name of music’. But that seemed to make people like us even more. It made them more curious. We’ve been called everything from alternative to electro space zombies, Velvet Underground on Mandrax, punk – you name it. We’ve just carried on regardless! Through the years, goth has grown and widened tremendously, it’s absorbed more and more styles – there’s cyber goth, medieval goth, you name it goth. And people like Nick Cave, Siouxsie & The Banshees, Killing Joke and a host of others are now included, which they weren’t back in the 80s. A recent compilation even included Echo & The Bunnymen, so now I’m REALLY confused!

Des Morris, Balaam & The Angel

We were all very much fans of what was going on, but from a ‘musical influence’ point of view we were somewhat different. Our major influences were the likes of Patti Smith and the Doors. We were individually inspired by the punk movement and very much so by the post-punk movement (Joy Division, Magazine, Gang Of Four, Killing Joke and so on). When we set out to promote our brand of music we actually made a point of wearing white or colourful clothing to embellish our flavour of music – brighter and uplifting as opposed to the darker moods of that time. We wanted the image to complement the style of our music. In fact, the music journos back then had the greatest difficulty in finding a pigeonhole to put us in. So I guess we are saying that in some quarters we were viewed negatively and quite possibly unjustly. The whole concept and mystery was totally our own individual evolution and we are very proud of it.

Christian Riou, Claytown Troupe

Claytown Troupe were described by Steve Lamacq as goths in brown rather than black – I guess the Damned had that vibe. We crossed into all youth areas. Goths, punks, heavy metal, grunge, even skinheads in those days. Our gigs were a right mish-mash of styles, but the goth following was different then. We were filming [Riou currently works for a facilities company] Bullet For My Valentine the other week. I was stood on stage watching them. Apart from there being no vibe, they looked like yer average Claytown/Cult/NMA follower in ’89, but played heavy metal. That’s the influence right there – it goes punk, goth, grunge, goth metal, emo!

The goth scene became very different in the 90s. It took on the indie torch and went very underground. I went to Nine Inch Nails’ first gig in New York in ’89 in a tiny cellar. There were about 50 people there, and to be honest, I thought it was like watching Alien Sex Fiend, who we supported once. But they effectively re-invented goth to the Americans and to the Cradle Of Filth generation – more theatre and death metal than the punk roots it came from.

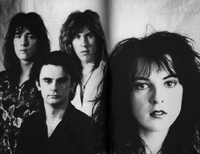

Julianne Regan, All About Eve

I’m totally comfortable with it [the goth tag] now, but it wasn’t always the way. I imagine many bands feel the need to rebel against the label they are given, and we were no exception. Our roots as a three-piece band were in goth – I was listening to the Banshees, Bauhaus, Cindytalk, Joy Division, the Cure, the Cocteau Twins etc. So there was bound to be at least an undercurrent of darkness in our songs. At some points, we may have been guilty of mild plagiarism! I’m not massively knowledgeable about the goth scene now. I see bands such as My Chemical Romance and Evanescence as a kind of sanitised goth, scrubbed up for a mass market. Not that there is anything wrong with that, and I may be doing them a great disservice. In fact, I have heard a few Evanescence songs I like, but the great thing about them is Amy’s voice. It’s as technically brilliant as Christina Aguilera’s (and no, I am not being facaetious!) There is a debate about whether Marilyn Manson is or isn’t goth, but I think he’s a lot closer to ‘real’ goth than many of his contemporaries. I saw him live at Ally Pally a few years back and it reminded me of seeing Bauhaus at Walthamstow Town Hall in about 1982. It was edgy and theatrical. In our earliest days, I don’t think goth had yet become really a fully-fledged ‘movement’ as such. There were bands around such as UK Decay, Southern Death Cult, Sex Gang Children etc. It was a disparate bunch that often only seemed to have the wearing of leather trousers and eye-make up in common, alongside an energy that seemed to have a whiff of punk about it. I certainly don’t remember goth being much ‘fun’ at all though, I felt cosy in the darkness of it – until the Mission came along. They injected a feel-good factor into it somehow, made it more about the dressing up box and the wine cellar! It was like they’d lit some candles in the crypt!

Simon Hinkler, The Mission

It was inevitable that The Mission would be tagged as a goth band, because of the past association with The Sisters. In reality we all had a different take on what we were doing. Mick [Brown] and I saw ourselves as a rock band, and Wayne [Hussey] definitely wanted to lean more towards pop songs. That generation of bands that acquired the goth tag were, for the most part, quite diverse and didn’t necessarily want to be lumped together under a category. The fans perpetuated the stereotype to a much greater degree than the bands themselves. In fact, I clearly remember a significant number of Mission fans (the seriously goth ones) being turned off. Not because we’d had a chart single or whatever, but because a couple of band members had their hair cut short – which I think is strong evidence to how ridiculous the whole thing is. It seems to me that in the years to follow, the bands who had grown up listening to that period of so-called goth music diluted it into a pastiche, and by so doing reinforced what goth supposedly was. It’s interesting that now there is a definite contingent of bands who willingly call themselves goth. From what I’ve heard, it’s blatantly derivative, and sadly lacking spark or originality. Apparently now there’s no need to serve any other purpose than the perpetuation of the goth tag that was (after all) initially fed to the public by those lesser people in the media business.

Andy, Resurrection Records

Joy Division, who are so ‘bang to rights’ it’s not even worth arguing about, Siouxsie, the Cure and the Damned all had a goth phase while goth (or positive punk/post-punk as it was then called) was the big thing. They are all bands that jumped on the goth bandwagon as soon as the punk scene fell apart. It’s just that they existed before the media invented the tag and all released one album before developing a goth audience, apart from Joy Division who went straight for the goth sound. This is back in the days when this was the most popular style of indie music around and the Goth (positive punk) scene actually was the mainstream, it just wasn’t called goth until years later. It’s important to note that although they became some of the biggest names, they weren’t the first ones there. They were as much influenced as influences. These bands were all under ‘major label influence’. Whether pressurised or not, it’s unsurprising that just as they had moved on from their original roots in the punk scene, when the momentum of the ‘goth movement’ slowed in the mid-late 80s, they all lost their goth sound. They gradually began to appeal to a more mainstream rock and alternative audience (line-up changes were also involved here). Yet they still looked the part and largely relied on their original material and core audience when they play live. I think its a case of ‘once a goth – always a goth’, even if the precise definitions change over time