Faber have just published Totally Wired: Post-Punk Interviews And Overviews by Simon Reynolds. Here is an outtake in the form of an interview with Charles Hayward of Quietus favourites This Heat. We will be publishing an extensive interview with Reynolds, one of our favourite music writers, in a few days time.

CHARLES HAYWARD interviewed by SIMON REYNOLDS

(interview originally done in early 2001)

This Heat seem like an archetypal post-punk group. But it actually had all these links to the UK’s pre-punk progressive underground. You were in Quiet Sun, Phil Manzanera’s outfit, right? Who in 1975 put out the album Mainstream, which was kind of proggy-fusiony? So just a year before punk, you’re on the wrong side of the coming divide, basically!

CH: "I had been at school in Dulwich with Phil Manzanera and Bill MacCormick. We started out playing blues stuff, and then moved on from there; started writing our own songs. It became Quiet Sun and it developed into the kind of stuff that The Soft Machine were doing, Frank Zappa, those sort of people."

Oh, all this was before Manzanera joined Roxy Music?

CH: "Yeah. Then Phil joined Roxy, and Bill joined Matching Mole, Robert Wyatt’s group after he left The Soft Machine. So Quiet Sun went into non-existence. Then Phil Manzanera had a chance to record a solo album, Diamond Head, and got two off the back of one, so to speak. We had 4 days of rehearsal and then recorded Mainstream."

You can definitely hear that Canterbury Scene influence in This Heat, especially the vocals, which are quite Wyatt/Hatfield and the North.

CH: "We were into it all of that stuff, but became bemused by their reliance on technique. With This Heat, we wanted to have more of an elemental feel, as opposed to the sophistication thing of playing five beats to the bar. And that was helped by having Gareth Williams in the band. He couldn’t play a note when he joined. It made the whole thing more open, and more up in the air, so to speak. We had to find textures and sounds, as opposed to a nice jazz-based solo."

How did This Heat come together?

CH: "Charles Bullen I met from a Melody Maker advert. I’d been working with a sax player and we were looking for a bass player and a guitarist. Charles turned up and interested me more than the guy I was working with. So we played as a duo and also played in other bands around at the time, which would have been around 1974-75."

What was the vibe you were pursuing then? Was it more oriented to the pastoral, dream-drifty, whimsical thing that tended to dominate the UK progressive underground then?

CH: "We were listening to a lot of angry New York free jazz. A lot of Sun Ra. That went back to the Sixties actually. I’ve got this archetypal story of being thirteen and in Brussels with my parents and me desperately trying to negotiate some way to stay on an extra day so I could see Sun Ra perform. I spent thirty quid or something on this very expensive ticket. That was 1964 or ’65. Charles and I were doing a lot of open improvisation. We’d record one side of a cassette, listen to it, flip to other side and record over it, listen to that. That would be an afternoon’s rehearsal. We didn’t know what we’d done until we listened back to it."

In This Heat’s music there’s such a range of sounds and sources – there’s improv, there’s dub, there’s a musique concrete element, there’s sounds that a bit later would probably be labeled "industrial," weird little traces of ethnic and world influences…

CH: "In 1973 I was in Bullen’s flat and it was the first time I heard that album on Nonesuch that is the archetypal Bali gamelan record. The one with ‘Golden Rain’ on one side and ‘The Ramayana Monkey Chant’ on the other. Bullen had a beautiful record collection that later got stolen. Southwark Music Library was down the road from where I lived, so in 1968 I was listening to things like John Cage’s Fontana Mix and Stockhausen’s Kontakte. And Charles had been educating himself with the same kind of stuff in a parallel way in Nuneaton.

"I was from Camberwell. And it’s important to me that music which goes ‘outside’ still has some sort of semi-folk basis in society. It belongs to a place and comes from a place. Which is something I always hear in Sun Ra. They were part of a community in Philadelphia and Washington, even though their music doesn’t overtly describe the situation they lived in. Everyone nowadays is basing their morality and ethics on gadgets, as if a sense of place doesn’t exist anymore. People feel dislocated when they haven’t got that. I’m working with special needs people, the so-called disabled. I work alongside all sorts of people and then I’m trying to assimilate those experiences and do my own synthesis of what it is to be with people and make that come through in my music."

So when did Gareth Williams enter the picture?

CH: "Gareth entered when he managed one of the groups Charles and I were in, Radar Favorites. In an act of pure lunacy, he’d turn up to meetings in a yellow silk smoking jacket. He was an energy man, an insane humour man who could drive things into a frenzy. The fact that he couldn’t play a note was exactly what we needed. He was grappling with the instruments in a way that was related more to life than music. It was more like trying to operate a vacuum cleaner than having a conservatory-trained piano technique. Gareth immediately fit in with what [improviser/London Musicians Collective patron saint] Han Bennink was doing at that time, having this element of clowning, juggling. Bennink is a drummer really, but his whole thing would be like controlling this chaotic situation. Gareth would often provide that role for us. Sometimes it would just be down to him playing one note on a keyboard for 12 minutes and slowly manipulating all these effects pedals, making music out of just a single note. It was a refocusing of what ‘technique’ was. Instead of andante or legato it would be ‘angry’ or ‘stumbling over’."

Whereas you and Charles were much more grounded in musical technique?

CH: "I’d had classical tuition in piano as a kid, so I knew my scales. Then I’d had drum lessons when I was eleven until the age of twelve and a half. Later on I had six months with a blinding teacher, Max Abrams. But then I forgot it all. Rebelling against what you’ve been taught was important. But then after a while, you start to think, ‘What do I want to rebel against?. Rebel against what people taught you? Or make something that expresses the rebellion effectively?’ In which case, maybe some of the techniques are worth knowing. So I dredged them up from my memory. But not in early 1975, which is where we’re at in the story of This Heat."

In 1975, were you aware something like punk was on the horizon?

CH: "We were not aware that punk was going to happen. We were aware that what we wanted to do was commit some act of violence upon what it was to be a musician and what music was. And we knew there were people in the past who didn’t give a shit – fantastically elevated musicians like Sun Ra or Beefheart. We were aiming to make a positive contribution but with a certain aggression and reaction against the pomposity of people like Yes.

The word "violence"…I used to love and I still do love the first five or six singles by The Who. And they all express a sense of violence in the way chords were played and drums were hit. That was another model for me."

So what happened next?

Bill MacCormick and I got the chance to reform Quiet Sun, because Mainstream had gotten into the bottom of the Top 30. Phil Manzanera wasn’t in it anymore, so the promoter said why don’t you form a new group with a new guitar player, get Phil to come play the first or second gig, and then after that he’s just a guest. So we auditioned all these guitarists-–and by now my relationship with Charles Bullen was very close and I was pushing for him to be the man and that’s what we decided. Me, Bill, and Charles. I thought we needed some way to stop it from being a heads-down jazz-rock group and turn it into something adventurous and out-reaching, with overtones of performance art. So I suggested Gareth. He was no longer the manager of Radar Favourites because they no longer existed. He came down to London from Cambridge. But Gareth and Bill MacCormick hated each others guts instantly. After four days, I hardly saw Bill again. And Gareth, Charles and I really hit it off. It immediately took off. At first we called ourselves Friendly Rifles and then everyone was talking about the Sex Pistols so it seemed like a bad name and we had to change it immediately. This Heat was a much better name."

With your interest in "violence" and love of the early Who, were you attracted to the emerging London punk scene?

CH: "We started playing gigs and in those days we were all living on the fringe. Gareth and I lived in squats, and Bullen was renting but living in this horrible place. We all had no money at all. So we started doing these early gigs and then we read about the Clash. We knew there was a single coming out and we read about them having this lyric, "No More Beatles, No More Stones". But then we heard the song and it sounded like ‘Johnny B. Goode’! Which is what the Pistols sounded like too. The first time I heard Alternative TV, though, I could hear a situation where people were riding this chaotic system. Partly because of their incompetence, partly because they were more ambitious musically than they had allowed themselves time to be able to be, technically. Alternative TV had this song ‘Alternative to NATO’ – I heard it live and I thought it was fantastic. It was almost a political treatise on having a viable alternative to NATO. It was expecting the world to change overnight, demanding the world NOW. Even if it didn’t make particular sense, its sheer fuck-offness was just so compelling. For us, hearing that song was like the first time we heard Archie Shepp. It immediately echoed Dada for me. Even its incompetence and its moronic-ness was part of that whole Dada thing. Anyway, some of these punk kids started coming to our gigs. We got to know CRASS. One of their girlfriends lived down the road from our squat. I got to know Steve Ignorant and all that CRASS lot. We’d go to their gigs and they’d come see us. At that point I was squatting in Depford."

So did you start to get embraced by the emerging postpunk scene? I remember reading about This Heat at the time and the sense you got was that this music was way way out there on the edge, it was this extreme and rather forbidding experience.

CH: "There was a wellspring that nourished us, this punk possibility. It accepted us and nurtured us, even though This Heat weren’t really part of it. Unlike a lot of the punk groups, we’d managed to get it together quite well. Well, Joe Strummer was well-versed in what it was like to live a practical life as a musician. But we took as our model Can’s studio, Inner Space. We came across this old disused meat fridge on Acre Lane, in Brixton. It had been turned into artist studios, Cold Storage. That gave us an incredible power base. We could pursue something over a long term, in much more detail than other people could do. It gave us the ability to do long-term work. We could spend a whole week there just using the Artificial Head recording system. That was this way of duplicating the parameters of hearing as human. Between our two ears we have this bone structure, the skull, so we hear one sound reflection off one wall earlier than the other. That’s how we locate where sounds are. So with the Artificial Head recording system you plug the mikes into a model of the human ears. Or even an actual pair of human ears. David Cunningham [Flying Lizards/This Heat producer] would wear the microphones as if they were headphones. We did a lot of that outdoors. The dichotomy was fantastic — we’d be doing rigorous experiments and playing aggressive live music in Berlin punk shithole clubs. And we’d weave these experimental tapes into the aggressive music.

This Heat had this really powerful mix, or collision, of quite rarefied pure sound stuff with really visceral, confrontational energy.

"We did stuff that was edgy and floaty, and then stuff that was dense [with] lyrics about politics. Suddenly you’d go into these other places. It was the switch from one to the other that was the true confrontation for me. People would be hearing with the cultural ears of one experience and they’d be confronted with a different set of things and for a moment they wouldn’t know how to listen. And that was what was important to me, making people listen in different ways, with different ears."

So you did the first self-titled album…

CH: "We made a demo which we spent a long time on. Very uncompromising. Instead of doing three minute pop songs we presented a 28-minute stretch of segues and jump-cuts which included ‘Horizontal Hold’, ‘Fall of Saigon’ and ‘Not Waving’ but also had all kinds of abstract stuff. And we did a B-side to the demo that was completely improvised but also had a lot of edits in it, about thirty edits."

Was it that kind of Holger Czukay approach to producing Can – they’d do the total-flow improvisatory jam, and then he’d snip and splice and piece together the best bits seamlessly?

CH: "We loved Can’s edits, but we were also inspired by Zappa, John Cage. A lot of the Pro Tools people today are using those techniques. With that technology, you get deceived by the clean-ness of the sound, but to get a performance out of it is very hard. The whole process slows down the flow. You go for getting things right instead of getting things to happen. But we were doing our edits with tape – and I’d make everybody keep every last little sliver of tape. I’d be: ‘It doesn’t matter if it’s not labeled, so long as it’s there.’ So there’d be bits of tape all over the place. I was terrified of losing something.

"We took the demo round the houses, which included John Peel. We hassled the poor bugger’s office every single day for two and a half months! He listened to us to get us off his back! But our determination impressed them. Peel likes people who state their case. Even now. And we stated our case. At the same time, we’d hooked up with Peter Jenner who ran this management company Blackhill Enterprises. Bit of a wide boy, he’d worked with Pink Floyd early on, Roy Harper, and at that time we hooked up with him he was having a lot of success with Ian Dury and the Blockheads. Jenner said: ‘I’ve got half shares with Manfred Mann in this studio on the Old Kent Road called the Workhouse and while we’re looking for a record deal for you, we’ll get you to start on that album. If the album sells to a company, then we’ll charge you at full studio rate. And if you get it out some other way" — referencing the independent label route – "we’ll do it at ‘dead time’ rate. " So occasionally they’d get a cancellation at the last minute and a whole day of studio time suddenly pops up. So that’s how ’24 Track Loop’ came about. We’d be at the Workhouse studio, so we’d get the loop out and then edit that down. It was like: ‘We have this dead time, everything is costing us a quarter of what it would normally’, so we’d really experiment. And then we took the Workhouse tapes and mixed them up with tapes of our early gigs, so we’d be sticking in bits of 2-track mixed in with all high quality studio stuff. That was part of that whole Sniffin’ Glue cut-and-paste aesthetic, it was in the air. ‘Horizontal Hold’, the opening bars are recorded in my mum and dads’ place in Camberwell and then it cuts to a plush 24-track close-miked studio piece. We’d be mixing up stuff that was Dolby and stuff that was not-Dolby. We were completely making up our own rules. And the engineers were going ape-shit. They loved it. We got no resistance at all from them. They had these amazing editing skills they couldn’t normally use – that whole thing of cutting up the tapes is more to do with what George Martin did with The Goons, that Radiophonic kind of stuff.

When did David Cunningham get involved?

CH: "He introduced himself to us at a gig and said: ‘That was the most aggressive, violent thing I ever saw in my life.’ And it was David who put in the word for us about the studio in the old meat pie factory. This was 1976. He’d recorded the Flying Lizards stuff but he hadn’t released it yet. Peter Jenner thought David was slightly more reasonable than This Heat, so he got David to coordinate with us."

All this studio-as-instrument, tape-splicing, multi-track stuff you did – it’s a bit like a non-druggy psychedelia, in a way.

CH: "Part of messing with people’s head would be to very consciously provide some kind of grid – the drum parts in ‘Horizontal Hold’ were almost like graph paper – and then place objects against that grid. This Heat wasn’t psychedelic and drifty and smoky and droopy – it was much more hard-edged and Mondrian-like. Our intent was not to get people drunk or stoned with our music but to get people to free themselves up. It’s like psychedelic methodology, but with the characteristic post-punk coldness and dryness, the angularity and sobriety.

Were there certain sounds that connoted the late Sixties/early Seventies psychedelic/progressive template that you deliberately avoided?

CH: "We did use fuzz on the guitars sometimes and often did cross-fades, so there’d be moments when one sound was going away and then another one came in. And those became important melting moments. So there was a melty-ness at certain points, but it was never drippy. Like if you think of Dali, everything melting and drooping – it wasn’t like that. It was more like… Magritte.

The postpunk Zeitgeist was very sharp-edged, it was all about ‘time to wake up’. Demystification was the big word. It was abrasively anti-Romantic. But that was because it was an urgent time: music that was about blissing out or otherworldly what-not seemed decadent."

CH: "You had stuff like Yes, where the words were almost like they were written by a random computer program. It had no relation to reality–no relevance to the fact that, you know, you had the SUS laws, black guys getting picked up by the police all the time. We felt, if you’re going to have words, they’ve got to be about waking people up, getting rid of all the comfort blankets, making you face up to what was happening. I was living on just porridge. Porridge every other day. I could make seven pounds fifty pence last me a week. For about eight or nine months I was living on nothing. So those Jon Anderson-type of lyrics pissed me off something rotten, they had nothing to do with anything. At the same time, you had a lot of reggae coming through with lyrics that were very culturally conscious and militant, very clearly about African liberation. ‘Africa Must Be Free By 1983’. That was a source of energy for us. The idea of Babylon."

That was a very influential notion on punk and post-punk – the Rasta notion of the capitalist, neo-imperialist West as Babylon.

CH: "There was a nuclear policy forged by our elder and betters called M.A.D: mutually assured destruction. They were so crazy they couldn’t see they had identified their nuclear deterrence policy as MAD! The whole of the second album, Deceit, was about the fear of nuclear war. Charles Bullen put it this way: the first album, the blue and yellow one, that was the fear, but the fear not really understood yet. The second one was the fear too, but we were starting to understand what was making us afraid. At that time it seemed like it was a fait accompli that there was going to be a third world war. This was before America successfully seeded the clouds above Russia and destroyed their grain harvest for three years in a row. I think that’s really what went on – the CIA had this mechanism for ruining the Soviet harvest. That’s what I’ve heard." (Hmmm, Ed)

What’s the story with that EP you did called Health and Efficiency?

CH: "We all got into bicycles and we decided that we felt good after we ate well, and the music became clearer and the work became more joyful. That became part of our trip, to keep ourselves together so we could push the music even further. We wanted to put a vibe across that wasn’t the doom thing completely, that wasn’t ‘We’re being poisoned by toxins and can’t do anything about it.’ It was very anti-punk, in a way, because there was a lot of weediness in punk, it became a cult of defeatism. The whole goth thing. So we were responding to that."

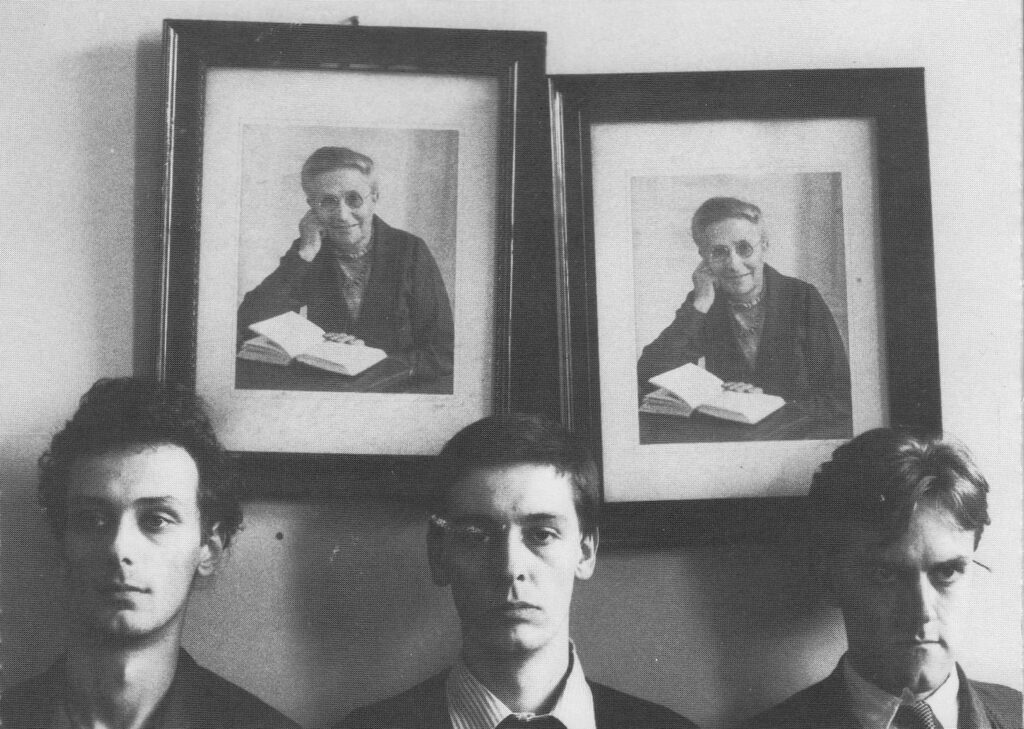

On the back of Deceit there’s this photograph of the three of you, and while I wouldn’t necessarily say you look ruddy with health, you do all look very cleancut and neat: short hair, clean-shaven, quite smartly dressed, a couple of you even have ties on. And you have these stern, almost frowning looks on your faces. So the whole vibe is austere and grave, it makes you think of pre-WW2 socialists maybe. And then behind you on the wall there’s two photograph portraits of a rather distinguished looking old lady reading a book. For some reason I imagine her as Edith Sitwell.

CH: "I’ve no idea who she was. We were in the Workhouse recording, and we had to do a photo shoot. And in the so-called restroom, there were two photographs of the lady, but in different parts of the room, so we stuck them together. Our look at that time was partly an image of pulling ourselves together – kind of: ‘How can we react to and resist these bastards who are so well organized that they can seed the clouds above the Russian harvest?’ But also it came from us liking to go to jumble sales. I had a lot of bus conductor jackets I’d picked up, and I bought handfuls of ties for 20p. Gareth was a maniac, he was looking at Masai tribesman haircuts and he got his hair cut like that. The music bred a sort of pride, and you had to manifest as much of its essence on the surface of the skin as you could. It wasn’t really an image thing, it was more like: ‘This is what it looks like to make this music.’

I read somewhere that This Heat once supported U2, of all people!

CH: "We got treated like shit by the road crew. There’s this hierarchy, when the bill is U2, Altered Images, This Heat, in that order of billing. So we had to attack the audience as rock fodder. We had this bit from a Demis Roussos song, going "I think I’m going out of my head", and Gareth had a machine that would do a very fast repeat, almost like an early sampler. So at this gig supporting U2, playing to two thousand people at the Hammersmith Palais… the audience were greeted with the three of us sitting onstage and Gareth playing this Demis Roussos loop over and over and over for 15 minutes. That was all part of our thing of getting your hand in the back of the radio, making connections with different parts of the radio and making weird electronic sounds come out."

Anything could become music.

CH: "Absolutely. Charles Bullen and I collected piles of broken instruments. We’d get broken toy pianos, half functioning speaking dolls. And we were doing sampling long ahead of its actual existence."

’24 Track Loop’ has these percussion sounds that almost sound like jungle, the pitchshifted breakbeats in darkside drum’n’bass. But you did that in, what, 1979, whereas darkside was 1993.

CH: "We did that with this thing called the Harmoniser. It meant you could give a tonal scale value to anything, like a drum. That album was the Harmoniser sessions. When I think about what Cage, Pierre Henry, Stockhausen were doing, and then you compare that with what’s happening today with laptop music, or Pro Tools. It would take Stockhausen a month to get 15 seconds of music when he was collaging bits of tape together. But the struggle is part and parcel of what comes out the other end. If it’s too easy, there isn’t that yearning inside it. No amount of niceness of reproduction quality makes up for that."

On Deceit, there’s the track ‘S.P.Q.R.’ and the lyric goes: ‘We are all Romans.’ What was that about? The inevitable decline and fall of the West?

CH: "Basically it was saying, we still build our society around these centralized nodes of power. The lyric goes: ‘We know all about straight roads.’ It’s not roads anymore like with the Roman Empire, but telephone wires or something else. I was also trying to bring in some historical information and make that part of rock & roll. That’s why "amo, amas, amat" is part of the lyrics. Instead of using this nice education I had a kid as a weapon… it’s much better if I say: ‘I happened to learn this, if we investigate it from this angle it might be useful.’ It’s not a class thing anymore, just put it in the pot with everything else. So it’s not being scared of being intelligent or informed. If you’ve got information and insight of a particular sort, that’s your tool for connecting to people."

Who were This Heat’s allies in those postpunk days? Your peer group(s)?

CH: "The whole improvised music crowd. Evan Parker was a god. He’d made these records himself and worked completely independently. He was also very rigorous and applied in what he did. Later, out of the punk thing, people like The Raincoats. They were presenting a very feminine, women’s sensibility that hadn’t been heard before. The way Palmolive used to play the drums, I adored it. And the fact that Ana was completely unversed in music-making but was the most ambitious structurally of the four of them. She was using her lack of knowledge as a way of making these open structures happen. I worked with the Raincoats later on. I was on Odyshape, half of that record. And I did two tours with them. Ana would say: "I don’t know how to make these go together, so help me, or we’ll just go from one bit to the next." Also, very early Pop Group was extremely exciting. The thing about them, they had all these songs and all these lyrics. When they did the first album they stuck all the old lyrics on completely new music! The first lot of songs they had when they played live early on were incredible and that lot has never been recorded.

"As postpunk went on, things were getting completely unfixed, everyone was in this state where it started to get really less and less about music, but more about putting different sorts of information and ideas across. People like the Red Crayola – they’d make backing tracks in the studio and just stick lyrics on top. Scritti Politti were working a bit like that. I found that by the time the punk thing had become the post-punk thing, some of it was super intellectual and super ideological. And it started to lose any musical feel. A certain amount of repetition gives the music structure. Lyrics have a cadence and if you try to defy that it sounds ugly as hell. There started to be a bit of a dour Russian Social Realist thing coming in. ‘None of this beauty shit matters, we have to inform the proletariat!’ Which is missing the point. If you can’t give it some beauty, even [if] it’s a very convulsive beauty, a new beauty made out of poverty. It’s still got to have some idea of beauty. So I was starting to part company with some of those people. With The Red Crayola, I had loved the Soldier-Talk era stuff, their thing of doing a song with no bass player on, because if you’ve not got someone who plays the instrument, then fuck it. But when they did ‘Kangaroo’? I just couldn’t get into it. Red Crayola went off into this thing of polemic with musical accompaniment. That’s the way with stylistic movements such as punk, by the end they tend to cut off one part of your body and over-emphasise one other part. That’s what happened to punk when it became post-punk. I’ve got this image of Led Zeppelin as this sketch of a human being all out of proportion. My picture of Led Zep is a man with testicles so inordinately large that he’s standing on them, he’s screaming in pain. It’s all one thing and nothing else. Whereas This Heat was about being totally human – not just a brain, not just a body, and not just emotional. People think intellectuals should be dispassionate; other people say you should just get into your body and groove, man. It’s all these different things at once that make you complete."

Deceit came out on Rough Trade, which was quite the post-punk power spot in those days. And with you working with The Raincoats, This Heat was very much at the heart of that milieu.

CH: Rough Trade gave us a lot of feedback. Pete Jenner had bowed out by this point, he was: ‘You guys get on with it.’ But Geoff Travis was really encouraging, he was very much like: ‘You must meet X’, ‘Have you heard Y?’ He was connecting us with the Raincoats and also with Robert Wyatt. We had been on the edge of everything, in our own little scene, operating on our own, a bit isolated, and suddenly we were plugged into something bigger. There was also an efficient pooling of resources going on at Rough Trade. But then towards the end, it became a bit like: ‘Oh here’s another organisation that has to perpetuate itself.’ Rough Trade got interested in having hits. Like, Young Marble Giants, when they came through at first we thought they were fantastic, they were just young people who completely weren’t responding to the dictates of punk. But then when it got to be Weekend [Alison Statton’s post-YMG group] and Working Week, and this French pavement café chic, nice Fifties dresses from jumble sales… My wife and I loved that kind of thing but then it became a fashion imperative. Rough Trade did respond to the whole New Romantic thing by going along with it, not fighting against it. And they needed more money to keep their staff in place. There had been a lot of talk by Geoff Travis about actually changing society, and then somebody went ‘Boo!’ and they all changed tack. Instead of just keeping going on as it was originally, but getting rid of the dead wood and changing our strategies. The multinational music corporations started to see that independent labels could be a glorified research-and-development operation for them. And then that’s how the independent labels started to see themselves. It all seemed very different by the early Eighties and I got disillusioned by this ‘Meet the new boss/Same as the old boss’ syndrome. I wasn’t going to be bought out and end up giving in. So what I learned from This Heat was to work with really small record companies. If there’s more than five people in the office, I get suspicious! I like to know everybody in the company, so there’s no strings attached to the decisions that get made."

Was this shift in the post-punk culture – the move towards New Pop and trying to infiltrate the mainstream, this cult of ambition and accessibility – was this something that contributed to the break-up of This Heat?

CH: "With Deceit, it had became very intense. We’d have these very intense recording sessions, then I’d come home and I’d be asleep for 20 hours. I was a healthy young bloke but I was exhausting myself. And it was like that for Gareth Williams and Charles Bullen too. So Gareth developed an interest in this North Indian dance, kathakali. He wanted to take a year out to do it. Now kathakali is a lifetime’s discipline so I thought he was losing it a bit! Gareth buggered off just after we made Deceit. And we’d wanted to gig for six-months non-stop, really make that record speak to people. Push it in more directions, make it a search and a quest, not this dead product. So when Gareth went, we did something stupid, we tried to make This Heat work with other members. Which was always not the idea. And the new guys inevitably ended up in a relegated position. It became like having session players in the band. We did a five-week tour of Europe and after that we knew it was going to finish. It’s a shame. Because we could have gone on forever."

Totally Wired: Post-Punk Intervwiews and Overviews is published now by Faber