In 1919 Robert Wiene, Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer couldn’t have known that their tale of a diabolical sideshow man and his freak would forever influence art and film. Tucked away in a corner of some garden, Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari begins with two men exchanging tales of their youth, it all seems mundane enough until we enter Holstenwall and the deranged mind of a genius art director. The resulting film is nothing short of inspiring and flawless.

Recently, I had the good fortune of seeing Caligari in its full glory, not sat in my sitting room but on the silver screen with a live accompaniment by Minima, thanks to Kino Sound and the Dalston Rio. As I watched Dr. Caligari wake Cesare from his endless slumber to the shock of the gathered crowds, the film took me down a road as yet untraveled.

Time and again I have watched the shadows creep and let the angles lead my gaze around the screen in a sold out viewing late at night surrounded by others, all in dead silence. But this time, I started to think about all the ways classic films can be taken in and interpreted – all the ways that this film in particular has been interpreted and the influences it has had on so many different people: from F.W. Murnau to Tim Burton, David Lynch to Frank Miller, from Bauhaus to Rob Zombie. When you watch a current film you tend to see it in the now, you relate it to today, not thinking where the film may go in time. When you watch a classic you are blessed with it’s history, it’s folklore and your hindsight. You are given a chance to view it and appreciate it in a way that so many films will never be appreciated.

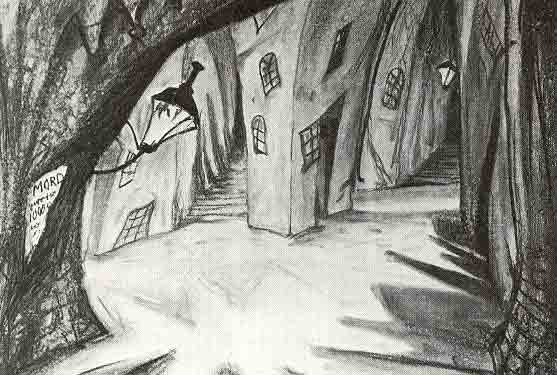

_Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari_was released in 1920 – inspired by a lonely stroll home returning from a local carnival and a chance encounter with some rustling bushes from which emerged a man. The next day the papers screamed MURDER AT THE CARNIVAL!! From that a script was written and sold and a film went to production. Caught up in a handover, the film needed to make something that would stand out against the cookie cutter films of the day, and thus came forth this expressionist masterpiece. Frame after frame, it delivers slices of artistic masterpieces – from the pained look in the eyes of Francis in the beginning, to the introduction of Holstenwall and Caligari himself, Cesare’s final flight over rooftops and through the woods, right through to the end – never missing a beat or forgoing art for content.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is the first psychological horror film, predating such classics as Peeping Tom and Psycho, which are often mistaken as the originators. But Caligari tricks you, makes you think one thing and then question it all. Who is who? Who is sane? What is happening?! The twisted world of Holstenwall must be the same dreamscape as Nightmare Before Christmas, mustn’t it? Or is it? The Asylum too looks frighteningly similar… what is actually real? Some answers are lost to time, war and book lice.

We are left with what we can see and take from it, the rest is guesswork. There are lots of rumours circling around Caligari and his cabinet. Siegfried Kracauer wrote From Caligari to Hitler in which he erroneously states that The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was an allegory for post-war Germany, setting it up for the Nazis to take power, Caligari (Werner Krauss) himself being the authority figure and Cesare (Conrad Veidt) the Somnambulist representing the German people sleepwalking into fascism. Kracauer didn’t bother to see the film for about 25 years before writing the book and couldn’t even have read the script which was at the time lost. His theory that a film made in 1919 could somehow be an allegory for events that were still 13 years away has been debunked time and time again. But never the less, the story has stuck.

Werner Krauss (Dr Caligari) and Conrad Veidt (Cesare), both powerhouses of Weimar Expressionist Cinema and specifically horror, starred side by side in 3 separate influential classics. Starting with Caligari in 1920, they went on to star in Waxworks in 1924, and finally in the 1926 remake of The Student of Prague in which Krauss reprised his commandeering role over Veidt as the devil in this updated take on Faust, which also enlisted one of the key set designers from Caligari.

One has to assume these two men were friends or at least friendly, the Hypnotist and the Sleepwalker, Balduin and Mr Scapinelli, sitting and drinking once again, chatting and whiling away the late evenings. As close as they may have been or at least their careers seemed to take them, their lives couldn’t have driven them further apart. Conrad Veidt, under circumstances never to be repeated, fled Germany, bringing his Jewish wife with him. Outraged at what his homeland was becoming he moved to England and eventually back to Hollywood (he spent a brief spell there in the late 20s) where he found plenty of new roles, including one starring alongside Joan Crawford. He even turned down the chance at becoming Count Dracula, as he thought his accent was too thick, and passed that now iconic role on to one Mr. Lugosi (whom he starred along side in the F.W. Murnau film, Head of Janus, sadly lost). Veidt later went on to play villains and spies and ultimately, as was needed at the time, many a Nazi baddie, most notably alongside Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca.

Our good Doctor on the other hand chose to embrace Nazism and all that it was. Carrying that banner high, Werner Krauss was made Actor of the State by Joseoh Goebbels and spent much of the 30s and half the 40s starring in propaganda films supporting the cause. After the war, this had an obvious negative effect on his career and Herr Krauss faded into obscurity.

Watching Caligari now you can’t help but have all this add to the film. So perhaps there was something in Kracauer’s theory, even if accidentally so.

In 1920, The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari was instantly recognised as ground breaking and 90 years later it’s power hasn’t waned. It is the pinnacle of German Expressionism, a visual joy and an enchanting story. It still seeps off the screen and continues to influence our world. Created as a response to the boring and bland cinema of the day, now, as before, this film can be viewed as it was meant to be, still standing strong against empty special effects laden atrocities that insult us around every bend. Part of the fun in watching Caligari is picking out all the little moments other directors borrowed and laid tribute to – a luxury only time could allow us.