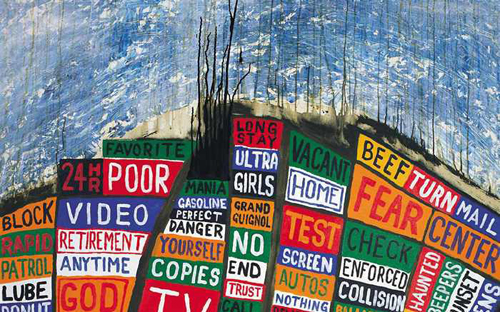

The sleeve artwork of Hail To The Thief, created by Stanley Donwood, was a series of maps of major cities in which the streets have been replaced by coloured blocks, emblazoned with malevolent phrases. London, for example, had districts renamed with the likes of ‘Spiked’, ‘Take You Down’, ‘Quango’, ‘Skinned Alive’ and ‘Shareholders’. It could have been an aerial view of the London of George Orwell’s 1984: the dystopian capital of Airstrip One, with Thom Yorke, his voice a lonely cry of aggrieved, affronted humanity, in the role of Winston Smith. ‘2+2=5’, the title of the opening track on Hail To The Thief, was the formula with which Orwell’s party invigilitator O’Brien demonstrated to Winston his utter powerlessness before the malign forces that ran his life.

I told Thom he could stop me any time he thought I was trying too hard, but. . .

“I did re-read 1984 a while before we did this record,” confirmed Thom, “but I’d forgotten where 2+2=5 came from. The other bit in the book I thought about a lot was the fake war – we’re at war with Eurasia, we’ve always been at war with Eurasia.”

I wondered if the utter, and brutally and perpetually reinforced, hopelessness of Winston’s position struck a chord. There was a line in ‘Scatterbrain’ – “A moving target on a firing range” – that seemed to sum up Thom’s view of most of humanity.

“It goes back to the Jubilee 2000 thing for me,” said Thom.

"You still end up with the reality that the IMF and the World Bank are there to keep everyone under their thumb" – Thom Yorke

He was, for a while, involved with Jubilee’s lobbying to get first world governments to write off the crippling, unrepayable debts owed them by third world governments. His optimism had evaporated some time before Bono’s. “I realised how out of control the disintegration was. When I started with Jubilee 2000, I thought it was the most exciting thing I’d ever got involved with. Potentially, we could show what’s been going on for what it is. But it never happened, because the G8 were very smart, and they and the IMF and the World Bank kept passing it to each other, and eventually I found myself thinking ‘Now I get it. It’s never going to happen’.”

I wondered if the experience had irrevocably persuaded him that – as the general tenor of Hail To The Thief appeared to argue – there was no point in trying to alter the system from without.

“No,” he said. “I’d like to be involved, but it’s difficult to know where to go with it. There were so many disheartening things about it, the fact that so much lip service was given, and you still end up with the reality that the IMF and the World Bank are there to keep everyone under their thumb. They affect millions of people, yet they’re completely unaccountable. I’d like to get involved again, but I find it difficult not to say that we should disband the IMF and the World Bank, to put it politely. Because that’s what I believe. Some people say you have to work within the structures, which is fair enough, because they’re the ones with the money. But if you do that, they’re just going to spin you a line. You get some money, but it’s money to make you go away.”

An experience that was reflected in the songs on Hail To The Thief, presumably. “Oh, completely,” he said. “I guess the whole record was a response to those experiences. Becoming a dad amplified it as well, because you start thinking not only am I powerless, but there’s an extremely dangerous set of things being set up for my son’s future that I can’t sort out for him. That’s quite a simple thing that’s very, very difficult to deal with.”

‘Sail To The Moon’, a song on Hail To The Thief, contained the line “Maybe you’ll be president / But know right from wrong / Or in the flood you’ll build an ark / And sail us to the moon.” Thom, I knew, had named his son Noah. I’ve always resisted, as far as possible, pestering interview subjects overmuch about their private lives. But since he’d sung about it, and though he was free to tell me it was none of my damn business. . .

“It wasn’t intended,” Thom smiled, “but it ended up being a song for him, yeah.”

While we’re up this way, then, I asked, why Noah?

“That’s what he looked like,” said Thom. “That’s what you do. Bugger the consequences.”

He’d get used to the ark jokes, I supposed. And the “It’s up to you, Noah Yorke” ones.

Oh, yeah,” grinned his father, who had lived down worse taunts. “He’ll be fine.”

In Thom’s list of thank-yous on the sleeve of Hail To The Thief, after friends and family, there was a nod to Spike Milligan. Radiohead had dedicated The Bends to the late American comedian Bill Hicks, another funny, outraged iconoclast. Hicks and Radiohead seemed a congruent fit. Both were intelligent, informed, acutely sensitive to hypocrisy – “Bill Hicks,” said Thom, “was able to make things that were incredibly frightening funny, and by doing that make them seem okay.” Milligan, whose best-known work was hyperactively absurd, seemed a less obvious choice of Radiohead hero.

“He did a TV series called Q,” recalled Thom, “which someone bought for me at a car boot sale, and I watched that a few times. There’s this one about a dalek coming home for its tea. ..”

The Pakistani dalek. I remembered that.

“Yeah,” said Thom. “The Pakistani dalek family. And every time I watched it, I thought, fucking hell, this is a person on the edge. There was another one where they wheeled in a staircase, and he just walked up and down it wearing costumes. He was so inconsistent, so incredibly spontaneous, and at the same time really fragile. There was also this book, Depression & How To Survive It, which he wrote with Anthony Clare. That had a really big effect on me.”

In what way?

“There’s one amazing bit,” continued Thom, “where they’re talking to people about whether there’s a positive side to depression. These aren’t people who are chronic, where it’s really out of control, but a lot of them say yes, there are positive sides. You see things in a way that other people don’t, and you feel things a lot harder than other people, and that’s good, it’s almost okay. It was good to hear people say it like that.”

“I went bonkers… Not violent, but. . . enormously, uncontrollably depressed, delusional.” – Thom Yorke

I wondered whether this had been a constant thing with Thom, or if there had been one particular period when it had been really bad.

“On the OK Computer tour,” he said, “we were in a situation where people were trying to persuade us to carry on touring for another six months, we should have said no but we didn’t, and I went bonkers.”

When he said bonkers. . .

“Oh, bonkers. Not violent, but. . . enormously, uncontrollably depressed, delusional.”

In what way?

“All sorts. Seeing things.”

That’s usually a sign that you should take some time off. . .

“No, actually. It was quite interesting. Sort of everywhere. Corner of the eye stuff.”

That sounded rather like the idea of the new album’s alternative title, The Gloaming: a twilight netherworld that you can’t quite see, but which you know is out there somewhere. I asked if anyone making the connection would be trying too hard.

“No, I guess not,” said Thom. “You know that film Ghost? Terrible film, but there’s this bit where all these shadows come down and take that kid away who gets hit by a car. That’s what it was like. We lost contact with reality, and got to feel like everything that wasn’t related to what we were doing was annoying or irrelevant. We’ll never do that again.”

A couple of months previously, I’d been to see Radiohead play in Edinburgh. Backstage afterwards, I’d noticed a volume of Spike Milligan’s World War II memoirs lying among the effects of Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood. Those books (Hitler: My Part In His Downfall, and several subsequent volumes) were, aside from being very funny, a tremendous expression of the bewilderment of someone being pushed and pulled by forces they cannot control – something they had in common with Hail To The Thief, and its obvious touchstone 1984. Thom, to my surprise, hadn’t read any of them.

“I will borrow Jonny’s, though,” he said. “You know, I think the appeal of Milligan is that he didn’t suffer fools, at all. Some people really hated him for that. But why should anyone bother? Life is short, and people are stupid. That’s definitely a depressive thing. You see the holes in things very quickly. Too quickly.”

The Costes hotel in Paris was everything Thom promised. The price of a room would leave some change from the Earth, but not much. The food was great, and all the better for the perverse thrill of paying twenty quid for scrambled eggs. The waitressing staff had apparently been hired by the expedient of placing an advertisement reading “Preposterously beautiful women required to work in absurd restaurant, ability to remember orders or maintain the merest facade of interest in customers unnecessary.”

When Colin Greenwood showed up – the only member of Radiohead who dresses at all like a millionaire rock star, – he was disappointed to learn that he missed Yves St Laurent

Those of us who’d arrived by bus parked ourselves in the bar with a bottle of champagne. A woman in a peculiar dress came over to tell Thom how much she liked the new album; Thom accepted the compliment graciously, and told her, correctly, that she looked like Alice in Wonderland, and this went over well. Neil Tennant dropped briefly by the table, and when Colin Greenwood showed up – the only member of Radiohead who dresses at all like a millionaire rock star, or indeed at all like anything other than a dishevelled student – he was disappointed to learn that he missed Yves St Laurent. The Costes was that kind of hotel.

Thom was one of the last to retire. He was an even better talker with a few glasses of fizz inside him, and he was funny, very funny, with his own failings the punchline to most of his anecdotes. Of Radiohead’s legendary appearance at Glastonbury in 1997, he remembered “That show was a disaster. Everything that could have gone wrong did. I thundered off stage, really ready to kill, and my girlfriend grabbed me, made me stop, and said, ‘Listen’. And the crowd were just going wild. It was amazing.”

Radiohead play ‘Karma Police’ at Glastonbury 1997

A few hours earlier on the bus, Thom and Ed had sat down to write the setlists for their festival appearances, and for the performance for French television that Thom and Jonny would be recording in Paris. In between lobbying as forcefully as I dared on behalf of my favourites – I believe I may have saved ‘Exit Music’ for some lucky festival-goers – I’d asked Thom if his position made it more or less difficult to articulate Radiohead’s hymns to humanity’s impotence. He was a millionaire rock star, after all, and presumably got to run his life more on his own terms than most of us.

“It’s easier,” he decided. “It’s easier, because you have more time to think about these things, more time to listen to Radio 4 and worry. But it’s sort of my job. Just like you’ve got your job, mine is to be the Ides of March type person, and some poor fucker has to do it. Somebody has to put the jester’s hat on and make a tit of himself. ‘We’re all fucking doomed.’ It might as well be me.”

Andrew Mueller doesn’t consider himself a "proper" journalist, yet he’s travelled from Afghanistan to Abkhazia, from Belfast to Belgrade and from Tirana to Tripoli in search of a good story. I Wouldn’t Start From Here is his random history of the 21st century so far, with all its attendant absurdities, horrors, and glimmers of hope. _It features gunfights, car chases and gaol cells, any number of exotic locations, and a cast of revolutionaries, rock stars, politicians, hitmen, warmongers and

peacemakers._ Whether ducking for cover in Gaza, running roadblocks in Iraq, hanging out with Hizbollah or getting arrested in Cameroon, Mueller is a man in search of an answer to perhaps the most crucial question of our time: What is it with these people?

<a href="http://www.amazon.co.uk/Wouldnt-Start-Here-Travels-Twenty-first/dp/184627151

7/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1199310356&sr=1-1">More on Mueller’s tome here.